Father Justin Sinaites, a Greek Orthodox monk from St. Catherine's Monestary in Sinai, Egypt, is in charge of moving the library of the Monastery into the 21st Century.

St Catherine's was built between 548 and 565 and is one of the oldest working Christian monasteries in the world, containing the world's oldest continually operating library, which holds ancient collections of liturgical texts, including some of the earliest Christian writings and is going to be made available online for scholars all over the world. The manuscripts which are kept in a newly-renovated building, opened to the public in December 2017, are now the subject of hi-tech academic detective work.

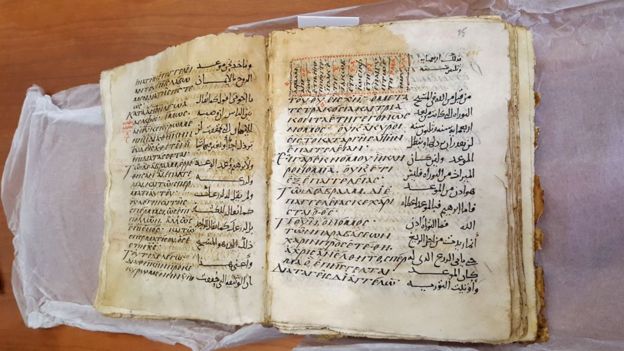

At least 170 of the 4,500 manuscripts in the collection are recycled manuscripts, known as palimpsests. Industrious monks often had to resort to scrubbing the ink off neglected tombs before reusing the parchment.

Working alongside Father Justin, is a team of scientists and photographers who have been using multi-spectral imaging to reveal passages hidden beneath the manuscripts' visible text. These include early medical guides, obscure ancient languages, and illuminating biblical revisions.

Among the researchers is Michelle P Brown, Professor Emerita of Medieval Manuscript Studies at the University of London. She was convinced from earlier visits that she could challenge the mainstream thinking that there had been little face-to-face contact between the far West and the Middle East between the 5th Century and the crusades in the 12th. Although the manuscript examined by Professor Brown had been discovered in 1975, it is only now that scholars have been able to distinguish the different layers using a variety of light waves.

The team found that part of the gospels had been made from an ancient Greek medical text which advised treating scorpion bites with a paste made out of a plant boiled in olive oil.

The palimpsest also revealed traces of Greek writing from the 5th or 6th Century, then Latin a century or so later, perhaps by hands trained in Rome and Sinai, then traces of two Anglo-Saxon scribes, before it was eventually used for the Arabic writing.

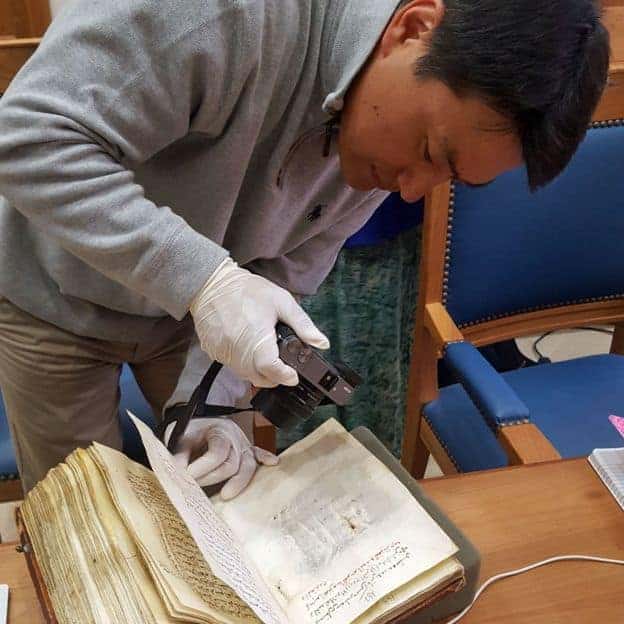

With terrorist attacks on Coptic Christians in the north of the peninsula, ”a lot of people are hesitant to come here [Sinai] because of what they read in the news," admits Father Justin. Yosoeb Song, a pastor studying at the Lutheran School of Theology of Chicago, had until a few years ago depended on poor-quality black-and-white microfilm to analyse an Arabic manuscript held at the monastery. In 2016, Father Justin sent him 269 high-resolution images. It was the first time he'd seen the red ink of the rubrics and sections that scribes had erased and written over, including the name of the person to whom the 8th-Century text had been dedicated. It was then he decided to come to Sinai and see in person the manuscript and what looked like medieval correction fluid.

Now, Father Justin is focusing on photographing the Arabic and Syriac manuscripts first to "reaffirm the Arabic-language heritage we have”. But with the political climate in Egypt, Father Justin says, it has become more difficult for Greeks, and by extension Christians, to stay in the country and easier for them to leave. "We are not foreigners that can be evicted. We are an essential part of Egypt's long history and we have to stress that.”

*Source: BBC