By Uzay Bulut

Greek basketball player Kostas Sloukas, who plays for Turkish team Fenerbahce, has been slammed for not holding a banner commemorating Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

The Greek City Times reported on November 12:

“Sloukas’ team Fenerbahce walked into the stadium holding a banner marking the 81st anniversary of Ataturk’s death just before their Turkish Basketball League match against Besiktas began, however, Sloukas stood back.

“The Greek guard was heavily criticized by Turkish media and on social media, including a Twitter post that was published by former Boston Celtics player Semih Erden, which showed footage of Sloukas not touching the banner but standing behind it.”

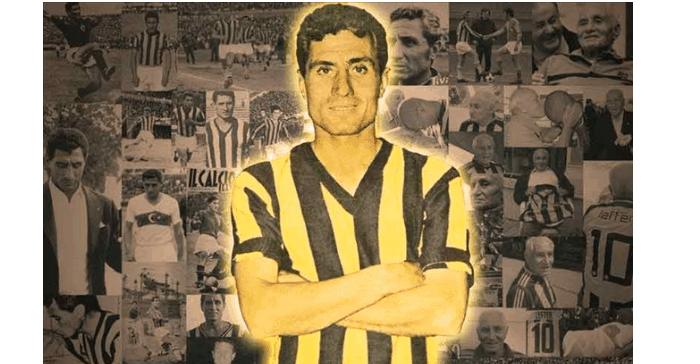

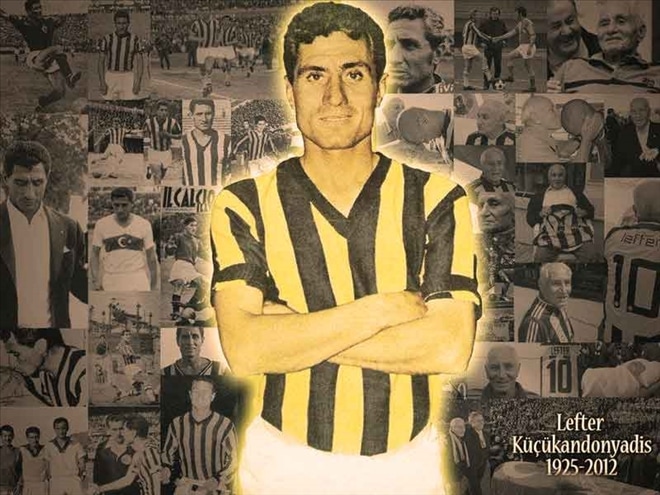

Sloukas is not the first Greek sportsman that has played for a team in Turkey. The harsh criticism that Sloukas has received makes it worthwhile to remember the story of the great Greek footballer, who was born, raised and tremendously suffered in Turkey: Lefter Küçükandonyadis.

Lefter (1924 – 2012) was born on the island of Büyükada in Constantinople (Istanbul). He grew up with ten other brothers and sisters. He transferred to Fenerbahçe in 1947 in order to be able to buy medicine for his sick father and achieved instant success.

He was capped 50 times for the Turkish national football team and was the captain nine times. He was the top scorer for Turkey for 33 years, but in many Turkish peoples' eyes, he had a giant fault, even a crime: he was of Greek origin. Hence, his life would never be easy despite his major professional accomplishments.

When he was 17, the Turkish government enacted the1 942-1944 Wealth Tax Law that targeted Greeks, Armenians, and Jews. Those who were unable to pay the tax were sent to labor camps; the government seized their properties, or they were deported. Journalist Rıdvan Akar, who wrote a book on the issue, called the Turkish government’s Wealth Tax policy “economic genocide” against minorities.

Journalist Nebil Ozgenturk, who made a documentary film about Lefter, asked him about what his family went through during the Wealth Tax Lawperiod. Lefter, a legendary footballer at age 87, did not want to or could not make comments on the record – even 70 years after the Wealth Tax Law – and asked the director to turn off the cameras. Leaning to Ozgenturk’s ear, Lefter said:

“They made my father suffer so much, too. He was saved from being sent on exile because of his poverty, but all of my family had to leave Turkey.”

Another crime against the Greek community in Turkey was the pogrom on 6-7 September 1955 in Constantinople. During the pogrom, Greek homes, shops, churches, monasteries, cemeteries, and schools, among other properties, were sacked, plundered and vandalized and, in some cases, destroyed. The Greeks were the main target of the pogrom. But the Armenians and Jews of the city were also attacked.

According to the HelsinkiWatch:

“The American Consul-General telegraphed the Department of State that the destruction was completely out of hand with no evidence of police or military attempts to control it. I personally witnessed the looting of many shops while the police stood idly by or cheered on the mob. A British journalist reported that the Greek neighborhoods of Istanbul looked like the bombed parts of London during the Second World War.”

Subsequent reports indicated that fifteen people had been killed.

“Besides the deaths,” wrote Professor Alfred de Zayas “thousands were injured; some 200 Greek women were raped, and there are reports that Greek boys were raped as well. Many Greek men, including at least one priest, were subjected to forced circumcisions. The riots were accompanied by enormous material damage, estimated by Greek authorities at US$500 million, including the burning of churches and the devastation of shops and private homes. As a result of the pogrom, the Greek minority eventually emigrated from Turkey.”

Lefter was living in Constantinople when the pogrom took place. During the pogrom, a group of Turks raided his house in Buyukada, screaming, “Hit that kafir (infidel)!” Lefter waited at his door with a gun in his hand until morning. Even though he knew all of the assailants, he did not report any of them to the police.

In an interview, he briefly talked about the pogrom: “15 days [prior to the pogrom] I was on shoulders when I scored a goal. But on that day, I was exposed to rocks and paint cans.

“The worst of it all was that the children to whom I had given pocket-money attacked my home. My daughters were very young. They tried to kill them. They asked me so much who did all of that. I did not reveal it on that day; I will not say it today either.”

Ozgenturk also asked Lefter about the pogrom. Before responding, Lefter first asked Ozgenturk to turn off the cameras again and said: “I cried for days. Don’t ask me such questions. You will put me in trouble. Yes, they deported us and made my father suffer. I still cry over the things my father told me. My father was such a poor man. Wasn’t what they did on September 6-7 a shame? It should not have happened, right? What else shall we speak about it?”

Ozgenturk told the daily Radikalthat Lefter’s words did not “even contain serious criticism,” which made his uneasiness even “more dire.”

“He said he was scared. He was a living legend, but he made me turn off the camera. It was so dire that he said, "You will put me in trouble." I could not even ask about the memories of the 30-year-old Lefter to the 78-year-old Lefter.”

Özgentürk said that he met Lefter twice – in 1999 and 2011. “He was a child of the poorest family in Buyukada. To me, he was a legend of football. But he did witness many people around him suffer. His brother moved to Greece after 1974 [Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus]. It appears that we [Turks] tried to hide the fact that Lefter spoke Greek and went to church. And his family accepted [this situation]. And we started perceiving even his name to be a Turkish name.”

According to Ozgenturk, the reason for the fear and unwillingness of religious minorities to speak about the crimes committed against them is that “the courage of minorities in Turkey has been taken away from them. Even the association of nurses would protest, but these people can’t.”

Sloukas wants to live and work in Turkey, but he is a Greek. Ancient Greeks built and enriched what is now Turkey throughout the history of the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. Only about two thousand Greeks live in Constantinople, the city they founded and made one of the great historic places in the world. This population collapse did not happen because Greeks did not enjoy the Turkish climate; they were murdered or expelled from the country of their ancestors, most during the 1912 – 1922 Greek genocide. Greeks who survived the terrible massacre of Smyrna (Izmir) and other murderous killings across Anatolia were sent to Greece under the 1923 compulsory population exchange between Turkey and Greece.

Every Greek who was born and raised in Turkey must have heart-breaking stories to share with Sloukas. After he considers the suffering of the Anatolian Greeks, Sloukas might make a wiser decision about whether to live in Turkey or not.

About the author: Uzay Bulut is a Turkish journalist and political analyst formerly based in Ankara. Her writings have appeared in various outlets such as the Gatestone Institute, Washington Times, Christian Post and Jerusalem Post. Bulut’s journalistic work focuses mainly on human rights, Turkish politics, and history, religious minorities in the Middle East and anti-Semitism. Bulut has now also become a contributor for the Greek City Times.

About the author: Uzay Bulut is a Turkish journalist and political analyst formerly based in Ankara. Her writings have appeared in various outlets such as the Gatestone Institute, Washington Times, Christian Post and Jerusalem Post. Bulut’s journalistic work focuses mainly on human rights, Turkish politics, and history, religious minorities in the Middle East and anti-Semitism. Bulut has now also become a contributor for the Greek City Times.