“There is one Greek family left in Ortaköy.”

The statement has recently been made by the Ortaköy Greek Foundation Chair, Strato Dolçinyadis.

“Expropriated in the 1980s, the Greek school has been returned to them as a result of their struggle at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). The revenue coming from the school is now used by the Greek Foundation to help the neighborhood residents in need regardless of their religious beliefs, says Dolçinyadis,” reported the Turkish news website, Bianet, on January 7.

Ortaköy (“middle village” in Turkish), called Agios Fokas in the Byzantine period and Mesachorion (“middle village” in Greek) later, is a neighborhood in Constantinople, built and once ruled by Greeks.

Constantinople, now termed Istanbul, was reinaugurated by Emperor Constantine the Great, who ruled from 306 to 337, and transformed the ancient Greek city of Byzantium into “The New Rome” or “Constantinopolis”, the City of Constantine.

From “Agios Fokas” in what was the capital of the Greek Byzantine Empire between 395 and 1453 to “Ortaköy” with just one Greek family in 2020 in Turkey… How did this population collapse happen?

From 1453 to 2020

The transformation of Asia Minor from a Christian, Greek land to a Muslim and majority-Turkish one began in the eleventh century with the invasion and settlement in the region of Turkic tribes originally from Central Asia.

These tribes who had converted to Islam from their Shamanistic religions by the end of the tenth century invaded the Armenian highland of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in the 11th century and started taking control of it.

Norman Itzkowitz, professor of Near Eastern studies, writes in his book “Ottoman Empire and Islamic Tradition” that “the migrations of the Oghuz confederation of Turkish tribes from Central Asia to Asia Minor ultimately gave rise to the House of Osman [the Ottoman Empire].

“It is sufficient to note that in the tenth century those indomitable steppe peoples were located in an area of Central Asia bounded in the south by the Aral Sea and the lower course of the Syr Darya (Jaxartes) River, in the west by the Caspian Sea and the lower Volga River, and in the northeast by the Irtysh River. They were largely nomadic, their wealth consisting of camels, horses, and sheep.

“By the end of the tenth century, Islam was securely established among the Oghuz Turks, who were now separated from the Islamic territories to the south only by the Syr Darya River.

“Once converted to Islam, the Turks began a southward expansion across that river under the leadership of the Seljuk family. The Seljuks started as military bands hired by Muslim princes and soon emerged as governors of provinces and eventually became autonomous rulers of vast areas. After overrunning Persia (Isfahan fell in 1043), the Seljuks struck out in a westerly direction. Under the leadership of Tughrul Bey, they thrust themselves into the settled centers of classical High Islam. Baghdad, the seat of the caliphate, fell in 1055.”

Itzkowitz also notes that “Islamized nomadic Turks known as Turcomans who were impelled by the love of booty and the desire to spread the faith of the Prophet Muhammed” were used by the Seljuks to facilitate their territorial expansionism.

“The Seljuks encouraged the Turcomans and other tribal elements to raid and plunder the eastern provinces of the Byzantine empire in Anatolia in order to divert them from settled Islamic areas. The Turcomans swelled the ranks of the Muslim frontier warriors, who inhabited the military borderland between Byzantium and Islam, were known as ghazis, or warrior for the faith. The sacred duty of the ghazi was to extend the Islamic territory (Darülislam, ‘Abode of Islam’) at the expense of the land inhabited by the non-Muslims (Darülharb, ‘Abode of War’). He did this by means of the ghaza, or raid, which came to be the perpetual warfare carried on against unbelievers, especially Christians. Wealth captured in this type of warfare was, according to the religious law of Islam, the sharia, lawful booty, and the inhabitants of the raided area could be enslaved or massacred.

“As the number of ghazis on the frontier increased, their raids became more frequent and venturesome, penetrating deeper into the Byzantine Empire in Anatolia…In August 1071 the Seljuks routed the Byzantines at Manzikert [Malazgirt] near Lake Van. Anatolia was now open to full-scale invasion and permanent settlement, and the long process of Anatolia’s Turkification and Islamization was set in motion.”

The Islamic Ottoman Empire was established in 1299 in Asia Minor. Steadily violating the boundaries of the Byzantine Empire, and finally reaching the heart of Byzantium, Constantinople, in the fifteenth century, the Ottoman Turks completed the destruction of the Byzantine Empire.

On May 29, 1453, after a seven-week siege, the Ottoman army, led by sultan Mehmed II, also known as Mehmed Muhammad the Conqueror, invaded and captured the city of Constantinople. Dionysios Hatzopoulos, a professor of classical and Byzantine studies, describes what happened after the city fell to the Ottoman Turks:

“[B]ands of soldiers began now looting. Doors were broken, private homes were looted, their tenants were massacred. Shops in the city markets were looted. Monasteries and convents were broken in. Their tenants were killed, nuns were raped; many, to avoid dishonor, killed themselves. Killing, raping, looting, burning, enslaving went on and on according to tradition. The troops had to satisfy themselves. The great doors of Saint Sophia were forced open, and crowds of angry soldiers came in and fell upon the unfortunate worshippers. Pillaging and killing in the holy place went on for hours. Similar was the fate of worshippers in most churches in the city. Everything that could be taken from the splendid buildings was taken by the new masters of the imperial capital. Icons were destroyed, precious manuscripts were lost forever. Thousands of civilians were enslaved; soldiers fought over young boys and young women. Death and enslavement did not distinguish among social classes. Nobles and peasants were treated with equal ruthlessness.”

During the Ottoman rule, Christians and Jews stood under Muslim law, the sharia, which imposes the inferior status of “dhimmitude” on Christians and Jews who accept Muslim sovereignty. Dhimmi is the subordinate legal status given to the “kafirs” (“unbelievers”) as a way to allow Christians and Jews to stay alive as non-Muslims in exchange for fees or high taxes, also known as jizya.

Despite these heavy pressures and oppression, Greeks and other Christians remained sizable communities across the Ottoman Empire until the final “blow” they received before, during, and after World War I.

1914-1923 Christian Genocide: Islamic Jihad and “Turkey for the Turks” ideology

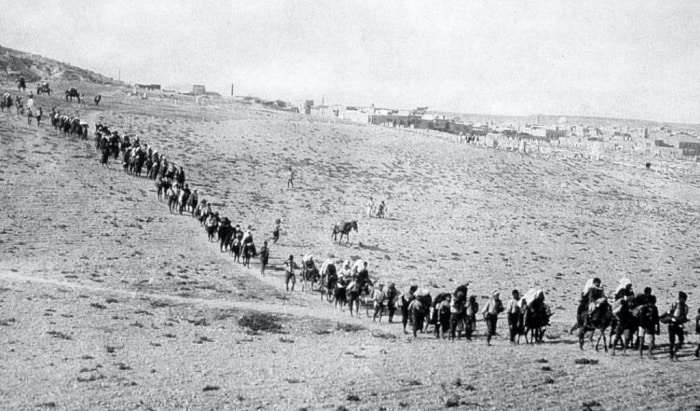

The Christian genocide that targeted Greeks, Armenians and Assyrians was carried out by the Ottoman regime of the CUP, Committee of Union and Progress, otherwise known as the Young Turks, and the successor nationalist movement that would establish the Turkish republic in 1923.

The genocide was ethnically and religiously based – Islamic jihad was a major determinant of the atrocities committed against Christians. On November 14, 1914, in Constantinople, capital of the Ottoman Empire, the religious leader Sheikh-ul-Islam declared an Islamic holy war (jihad) on behalf of the Ottoman government, urging his Muslim followers to take up arms against Britain, France, Russia, Serbia and Montenegro in World War I.

Historian Dr. Vasileios Th. Meichanetsidis notes in his article “The Genocide of the Greeks of the Ottoman Empire, 1913–1923: A Comprehensive Overview” that “The jihad was largely understood by the Muslim population as granting mujahids, or holy warriors, permission to attack, kill, and plunder (al-ghanîmah) gavurs [kafirs\infidels], as explained in the Qur’an and the hadith, or sunnah.”

The jihadi aspect of the Christian genocide is often ignored but it takes a little researching to grasp the religious motivations of the perpetrators. Historian Suren Manukyan, the Chair of the Department of Genocide Studies at Yerevan State University and Head of the Department of Comparative Genocide Studies at the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute, writes in his 2017 article “The Socio-Psychological Dimension of the Armenian genocide”:

“It is generally accepted that the planners of the Armenian genocide were neither inspired by Islam nor motivated by religious intolerance. But this is by no means decisive. In practice, they activated social forces by the policies they pursued, including the proclamation of jihad at the beginning of world war I, to mobilize religious fanaticism among the population of the empire.

“After the proclamation of jihad on November 14, 1914, the killing of Armenians was seen to bear legitimacy in religious terms. In many areas, clerics led the columns of Muslims and blessed them for punishing the unbelievers. This activated the traditional springs of religious fanaticism. From April 29 to May 12, 1915, parliamentary deputy Pirincizade Feyzi visited all the villages in Cezire, exhorting the Kurdish tribes to perform their ‘religious duty’. Feyzi incited these populations against the ‘infidels’ with the help of religious references and with the support of the hojas (Muslim teachers), rather than Turkish nationalistic discourse. One slogan was repeated everywhere: ‘God, make their children orphans, make widows of their wives… and give their property to Muslims.’ In addition to this prayer, legitimization of plunder, murder, and abduction took the following form: ‘it is licit for Muslims to take the infidels’ property, life and women.’”

Through jihad, the Muslim populations of Ottoman Turkey targeted all Christian subjects of the country. Meichanetsidis, co-editor of the book The Genocide of the Ottoman Greeks, lists other factors that are likely to have provided the ideological background to and justification for genocidal fate of Greeks:

“Traditional Turkish ethnic hatred against non-Turkish communities; traditional religious antipathy and fanaticism of Muslims against Christian infidels; and social, economic, and cultural envy for the Christian and culturally European Greeks…. The Ottoman citizens of Greek Orthodox religion were generally accused of being ‘treacherous’ and, ‘disloyal’, and seen as ‘protégés’, ‘agents of the Hellenic national state’, or ‘internal tumors’—as other Young Turk hardliners, too, put it… Greed also played a significant role in the process of radicalization.”

All these provocations – mostly in the name of jihad – led to unspeakably inhumane atrocities against Christians. Meichanetsidis writes:

“Having in mind the whole picture, we can conclude that the genocidal process against the Ottoman Christians constitutes the first massive destruction of citizens by their own government in the modern period. Under two consecutive, chauvinist regimes, the Ottoman Greeks suffered for the same reasons and from the same genocidal intent as their Armenian and Assyrian/Aramean compatriots, though methods, places, and motivations were sometimes different. The process continued even after the creation of the Turkish republic, the successor state of the Ottoman Empire, against the remaining Greeks of Constantinople, Imbros, and Tenedos and their institutions, the most important being the ecumenical patriarchate of Constantinople, which was a pan- Orthodox, pan-Christian, and inter-religious point of reference. In sum, from 1913 to 1923, the Ottoman Greek community was thoroughly destroyed through expulsion, massacre, war, and genocide.”

Many survivors of the genocide were then expelled from Turkey to Greece within the Convention on the Exchange of Populations signed between Turkey and Greece in 1923.

Sadly, despite the “secular” constitution of the Turkish republic, the persecution of Greeks and other non-Muslims continued during the republican period, as well. For example, in 1941-1942, there was an attempt to enlist all non-Muslim males in the Turkish military — including the elderly and mentally ill — to force them to work under extremely severe conditions in labor battalions; in 1942, a Wealth Tax was imposed to eliminate Christians and Jews from the economy; in 1955, there was an anti-Greek pogrom in Istanbul; and in 1964, most remaining Greeks were forcefully expelled from the city.

According to Professor Alfred de Zayas, the 1955 Istanbul pogrom “can be considered a grave crime under both Turkish domestic law and international law. In the historical context of a religion driven eliminationist process accompanied by many pogroms before, during, and after World War I within the territories of the Ottoman Empire, including the destruction of the Greek communities of Pontos and Asia Minor and the atrocities against the Greeks of Smyrna in September 1922, the genocidal character of the Istanbul pogrom becomes apparent.”

In 1991, Helsinki Watch carried out a fact-finding mission to Turkey and published a comprehensive report titled “Denying Human Rights and Ethnic Identity: The Greeks of Turkey,”which said, in part: “The problems experienced by the Greek minority today include harassment by police; restrictions on freedom of expression; discrimination in education involving teachers, books and curriculum; restrictions on religious freedom; limitations on the right to control their charitable institutions; and the denial of ethnic identity.”

Historical evidence reveals that Turkish officials were obsessively intent on destroying the Greek presence in Asia Minor. The Republican People’s Party (CHP), which established the Turkish Republic in 1923 and ruled until 1950, stated in its 1946 report on minorities that its aim was to “leave no Greek in Istanbul until the 500th anniversary of the 1453 conquest of Istanbul”, which would be 1953.

“Turkey used to be called Anatolia or Asia Minor and was a Christian civilization,” writes Dr. Bill Warner, the president of Center for the Study of Political Islam (CSPI). “Today Turkey is over 95% Muslim… Islam does not reach a balance point with the native civilization; it dominates and annihilates the indigenous culture over time.”

Dr. Warner appears to be right. In 1913, there were more than 2 million Greeks in Turkey. Today, there are fewer than 2,000 in Constantinople, or ancient Byzantium, the once capital of the Byzantine Empire. The annihilationist mission of Turks targeting Greeks has finally been “successfully” completed.

This article first appeared on jihadwatch.org and has been republished with permission.

About the author: Uzay Bulut is a Turkish journalist and political analyst formerly based in Ankara. Her writings have appeared in various outlets such as the Gatestone Institute, Washington Times, Christian Post and Jerusalem Post. Bulut’s journalistic work focuses mainly on human rights, Turkish politics, and history, religious minorities in the Middle East and anti-Semitism. Bulut has now also become a contributor for the Greek City Times.

About the author: Uzay Bulut is a Turkish journalist and political analyst formerly based in Ankara. Her writings have appeared in various outlets such as the Gatestone Institute, Washington Times, Christian Post and Jerusalem Post. Bulut’s journalistic work focuses mainly on human rights, Turkish politics, and history, religious minorities in the Middle East and anti-Semitism. Bulut has now also become a contributor for the Greek City Times.