The U.S. intends to force Serbia not to oppose Kosovo’s entry into international institutions, thus imposing Belgrade to indirectly recognize the breakaway province’s independence. In this way, the five EU members that have not yet recognized Kosovo’s independence would be discouraged from continuing this policy.

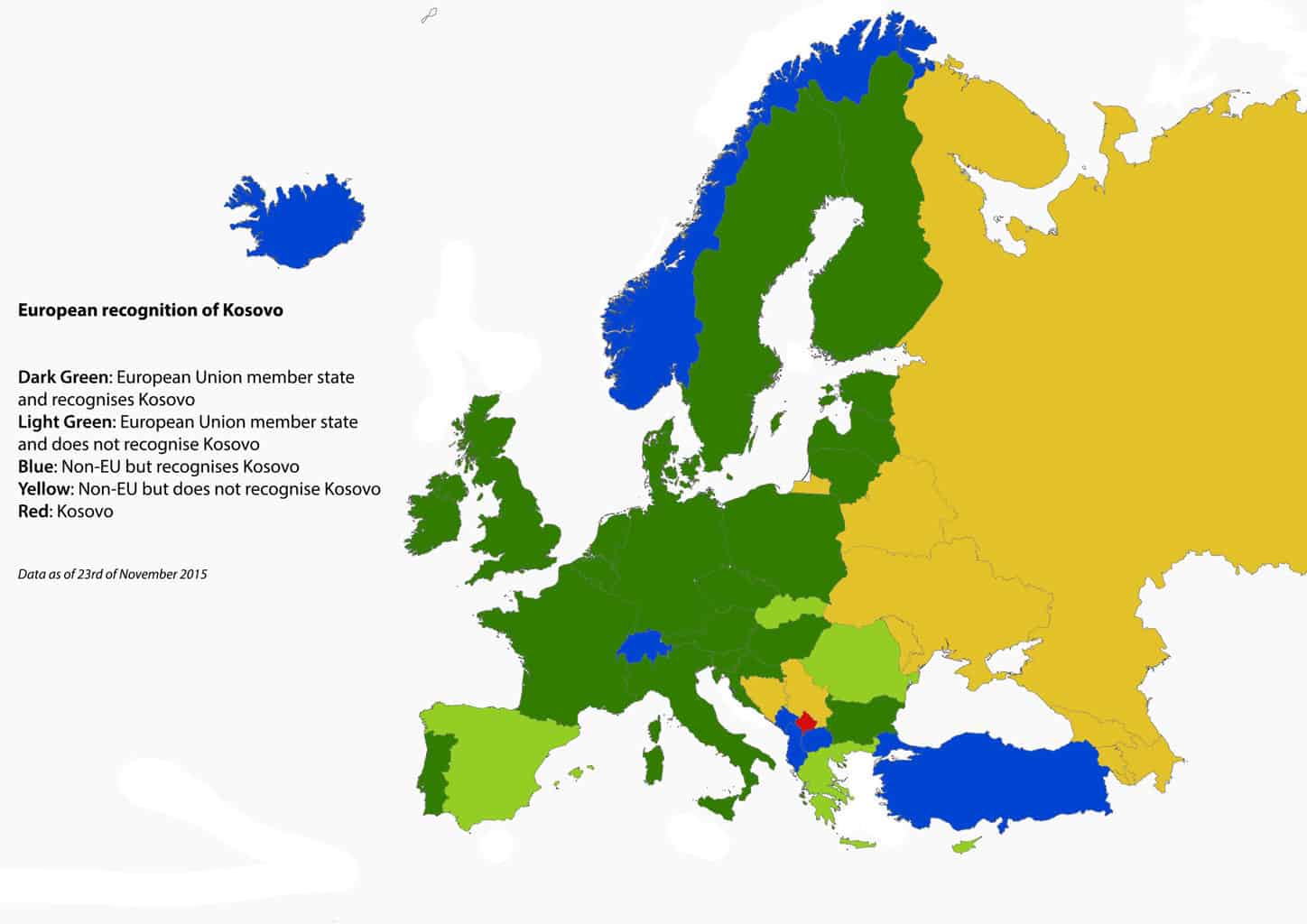

It is in the hope of U.S. Ambassador to Kosovo, Philip S. Kosnett, that Greece, Cyprus, Spain, Romania and Slovakia will change their position on Kosovo’s independence if relations between Belgrade and Pristina improve. Kosnett then compared the Kosovo issue to other disputes in the Balkans and the wider region that the U.S. has mediated in.

“Who would have thought that North Macedonia and Greece would reach an agreement on the name, but it did happen. People thought the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain or Sudan couldn't have relations with Israel, but it did happen,” he said.

However, these are not good examples given by the American ambassador. The sovereignty of North Macedonian territory was not disputed by Greece, but rather the name of the state was. The name dispute cannot be equated with a situation where the U.S. is backing an entity trying to secede 15% of Serbian territory. Also, the three Arab states do not have their sovereignty questioned by Israel. No matter how historical the issues over Israel and the Macedonian question may be, they cannot be put on the same level as Kosovo.

Kosnett's statement, given to Dukagjin Television, was addressed to Albanians who are accustomed to unconditional American support and is characteristic of Washington’s policy towards Serbia. Since the Brussels Agreement in 2013, Pristina expected the U.S. would make the five EU countries recognize Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence.

The 2013 Brussel Agreement, negotiated between former Serbian Prime Minister Ivica Dačić and his Kosovo Albanian counterpart Hashim Thaçi, and mediated by former EU High Representative Catherine Ashton, effectively opened a path for Belgrade and Pristina to normalize their relations since the provinces illegal declaration of independence in 2008.

However, the ambassador expresses a position that is consistent with Washington’s anti-Serb policy. This shows that the ultimate goal is to force Serbia to indirectly recognize the breakaway province through a comprehensive agreement and allowing it to become a member of international organizations. European countries that do not recognize Kosovo's independence would be discouraged to continue this policy. The position of the five EU member states that do not recognize its independence becomes irrelevant if Belgrade continues to allow incentives that further legitimize the Pristina government.

It is unsurprising that this attitude is being actualized on the eve of the 2020 American presidential elections. This indicates that the State Department hopes that it will become official American policy again. Although we cannot know with absolute certainty of this notion, it is indicative that Kosnett is speaking in that direction. It shows that there are strong impulses within the State Department which believes that the entire dispute and the relations between Belgrade and Pristina can be resolved by forcing Serbia to accept Kosovo’s independence.

There is a disproportion in Kosnett's statement between what the American ambassador would like to happen and the actual reality. Some of the EU countries would not recognize Kosovo even if Serbia reached an agreement to implicitly recognize the existence of an independent state in its own territory. But countries that do not have an immediate problem with their own territorial integrity would find themselves in an awkward position to defend their non-recognition if Belgrade is opening up to it.

Greece and Cyprus would probably not recognize Kosovo’s independence so long as Turkey continues occupying northern Cyprus. Spain too is dealing with several separatist movements, including in Catalonia, Basque and Galicia, and will also unlikely change their position on Kosovo. However, if Belgrade allows the breakaway province to be admitted into international organizations, there is a possibility that Romania and Slovakia could be open to recognizing the separatist province’s independence.

It all depends on the position of Belgrade, its strength to resist pressure and to find a long-term solution in negotiations with Pristina with the help of international mediators and within the bounds of international law. The possibly of Belgrade recognizing Kosovo would undo three years of diplomatic manoeuvring that has resulted in 20 countries withdrawing their recognition for the separatist province. As of today, 98 out of 193 countries recognize Kosovo’s independence after the withdrawal of the 20 countries. None-the-less, pressure is beginning to mount against Belgrade, and if it capitulates, the very few remaining EU countries that do not recognize Kosovo may begin doing so.