The Dodecanese (literally: “twelve islands) are a shining beacon of Greece.

Located in the south-eastern Aegean, they stretch from beautiful remote islands (such as Kastellorizo and Symi) to historically and politically significant islands like Rhodes, and encompass a total size of around 2,700 square kilometres and a population of 200,000.

Next year will mark 75 years since they achieved union with the Greek motherland, but the road towards that union was not easy.

One of the most interesting and overlooked periods in the history of the Dodecanese is the Italian occupation of the Greek islands in the early 20th century up until World War 2.

History of the Dodecanese and Italian rule

The islands have historically been inhabited nearly exclusively by Greeks (with occasional small minorities like Jews or Turks) for many thousand years.

This did not stop them from being controlled by various empires such as the Romans, Byzantines, Venetians, Crusaders and ultimately falling into the hands of the Ottomans in the 15th and 16th century.

Despite their 300+ year long rule, the Ottomans never really settled on the Dodecanese (except for some in Rhodes and Kos) and the islanders were left with much autonomy from the Sultan, only paying a special tax.

While the Ottoman Empire was in decline during the 18th and 19th century, the Dodecanese failed to achieve union with the small Greek state at that time because of their remote position close to Anatolia.

Yet the 19th century saw the dawn of another strong geopolitical player in the Mediterranean: a unified Italian Kingdom after the Risorgimento, and it was looking for expansion.

After emerging victorious from the Italo-Turkish War in 1911, the Kingdom seized the North African provinces of Tripolitana and Cyrenaica (later known as Italian Libya) and the Dodecanese islands, known to the Italians as “Isole italiane dell‘Egeo”.

In contrast to other Italian colonies, the Dodecanese were treated quite different - initially there were hardly any violent reprisals against the local population (unlike in Libya or East Africa).

On the contrary, it was seen as if the islands returned to their ancient Greco-Roman roots which inspired a heavy modernization process and enabled the prosperity of the Dodecanese.

The Italians strongly invested in infrastructure, built schools, hospitals (essentially terminating malaria in the Dodecanese), constructed aqueducts, modernised roads and brought electricity.

They also instated modern tourism and funded large scale archaeological projects on the bigger islands like Kos and Rhodes, which were very important in the Ancient world.

The architectural legacy is still present today, especially in Rhodes, as many public works built during the Italian Fascist era have been repurposed as government seats or enterprises.

Some of the most important buildings include the:

- Palazzo Governale,

- Teatro Puccini (now National Theatre),

- Grande Albergo delle Rose (now the Casino Rodos),

- Casa del Fascio (functioning as a City Hall), and

- Nea Agora (“New Market”).

This is in addition to the reconstruction of the medieval cathedral church of the Knights of St. John, among many others.

No such thing as a good colonizer

Having said that, one should not fall into the fallacy of believing in the “good coloniser” because such a thing does not exist.

The Italians, increasingly under Mussolini’s fascist rule (1922 onward), tried to integrate the Dodecanese into the dream of a new Roman Empire and therefore planned a heavy “Italianization.

This led to the repression of local Greeks, like limiting the influence of the Greek Orthodox church, and saw the Italian language become compulsory in local schools and the appointment of “podestas” (Italian mayors).

Italy also started settling Italian colonists, mainly on Rhodes.

While their numbers never exceeded 10,000 (excluding soldiers), it shows the intention in assimilating the Greek Aegean islands into broader Italian culture and rule which under Mussolini was planned to expand even into the Levant and the Middle East.

The Italian administration was fuelled by both nationalist and imperialist sentiments and one should not fall into the trap of believing in the “good coloniser”, it is an Italian revisionist tactic to downplay colonialism under the pretext of “Italiani brava gente”.

In the advent of World War 2 and the subsequent brutal occupation of Greece by the Axis forces 1941 (Germany, Bulgaria and Italy), the Dodecanese remained largely peaceful as they already were under Italian occupation.

This however changed in 1943 with the Allied invasion of Italy (The Kingdom essentially losing the War and switching sides).

The Dodecanese fell under German military control and ended the 31-year long Italian rule (the massacre at Kos being emblematic where the Germans lashed out their frustration at hundreds of Italian officers).

The islands only remained shortly in German hands, with the inevitability of their defeat, the islands went under British military administration in 1945, eventually being ceded to Greece under the Paris Peace Treaty in 1947.

Today Greece and Italy enjoy friendly relations, economically and especially culturally; a bond which is sometimes characterized by the Italian saying of “Una faccia una razza” (literally: one face, one race).

However, most Italians do not even know of their once occupation of the Dodecanese, let alone their territorial ambitions over them.

Still, it serves as an often overlooked and very interesting part of history.

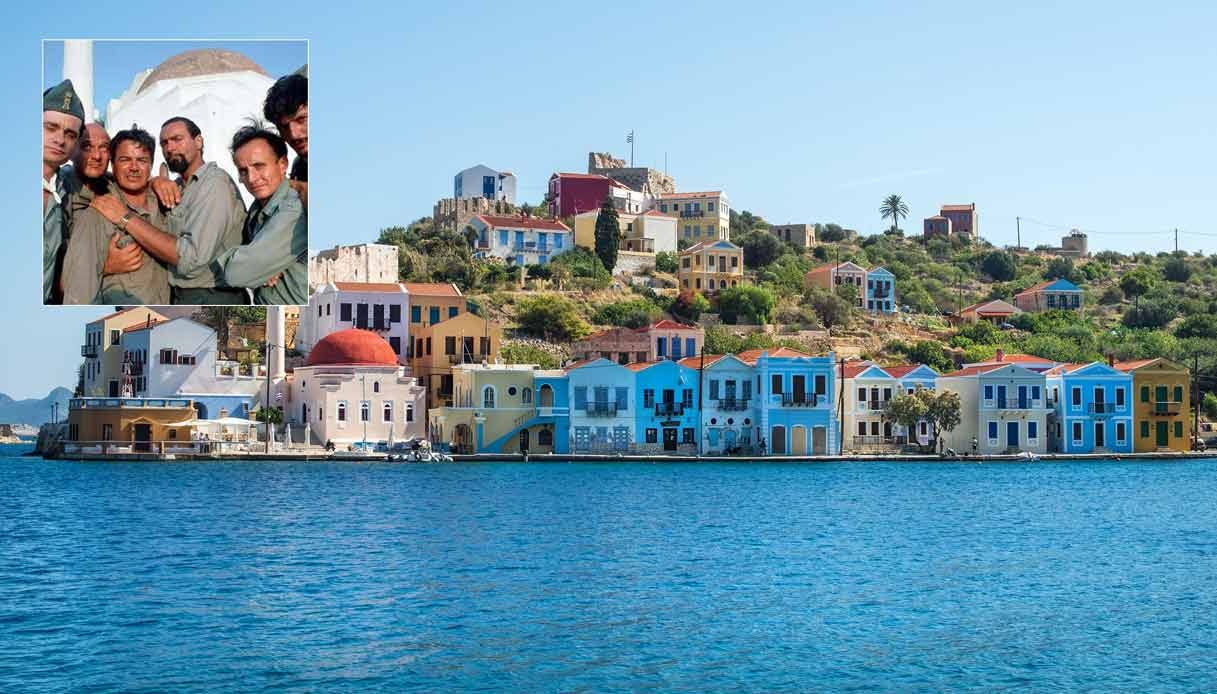

The 1991 film “Mediterraneo”, which won the Oscar Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and was coproduced by Silvio Berlusconi, deals with the Dodecanese during World War 2.

It shows how Italian soldiers interacted with the local Greek population on Kastellorizo.

It is a comedy on Greco-Italian relations, even if it is also an example of the “good coloniser” tactic that underplays the brutality of occupied Greece.

This article first appeared on Achilles Delta, you can follow his Twitter account here.