Greece's demographic crisis and the Convergence of Catastrophes.

Every country has complications and problems that they need to deal with. Yet none of those are as far reaching and important on a level of national preservation as the demographic crisis that Greece, among other (especially European) countries, is facing.

What exactly is the demographic crisis?

At its core, the demographic crisis means the lack of sufficient births (resulting out of low fertility rates) to replace an already aging society.

Its logical consequences are a stagnate, then declining population, which in turn brings larger socioeconomic dilemmas.

Let’s take a look at Greece:

The so called “replacement level fertility”, meaning the female fertility rate at which population remains constant without migration, sits at 2.1 per woman.

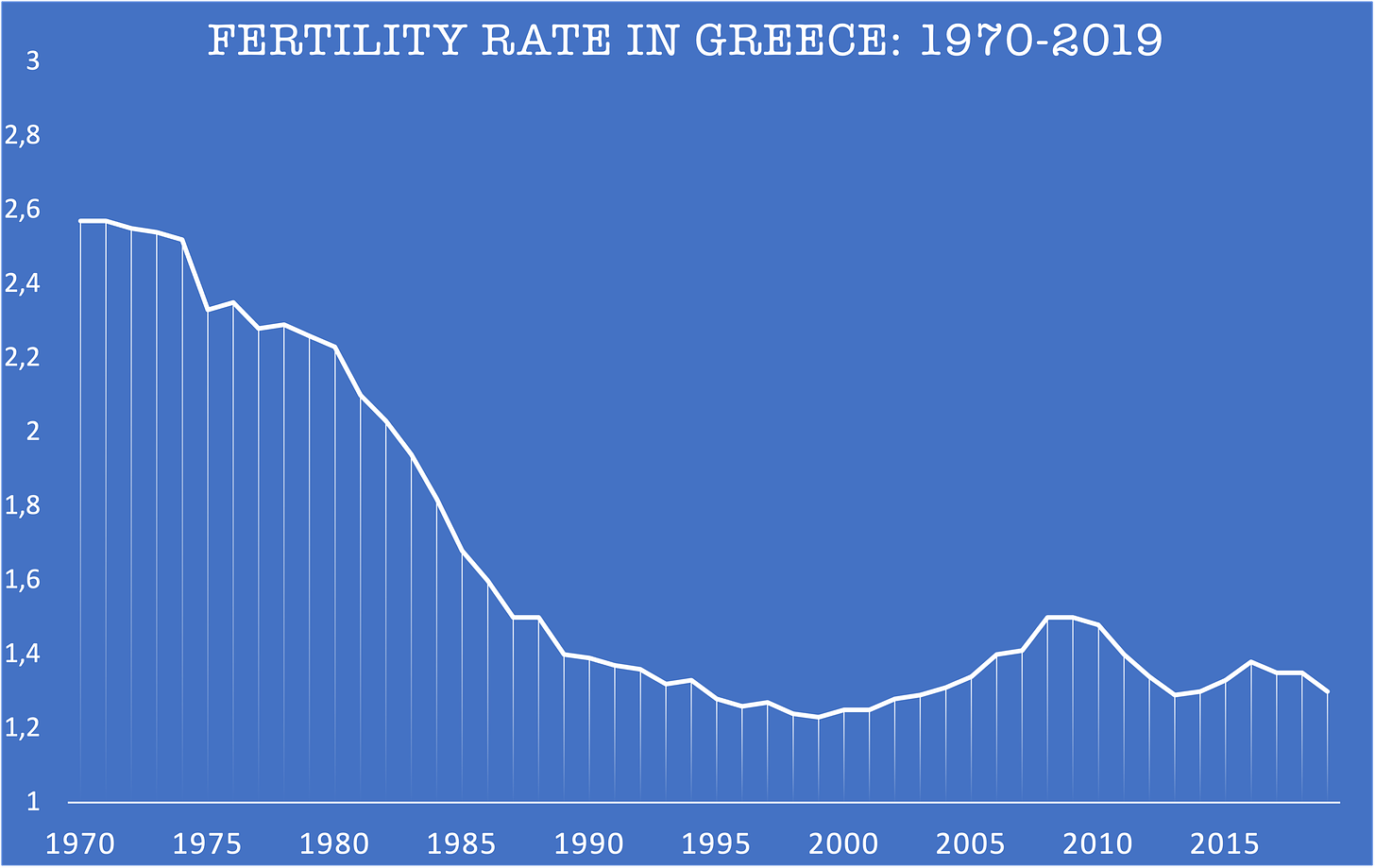

Greece’s current fertility rate sits between 1.3 and 1.4.

In fact, the fertility rate dropped below the replacement level as far back as 1982.

This has led to a significant drop in births per year (from nearly 150,000 in 1979 to barely 85,000 in 2020) and since 2011 to a continuous decline in the national population (from 11,120,000 in 2010 to 10,720,000 in 2020).

Greece is set to lose more than 40,000 people each year in the future.

Such developments are obviously unsustainable in the long run, and not tackling them as early as possible will turn out extremely catastrophic.

The fertility rate of Greek women is one of the lowest in the entire world, and it has been this way for many decades now.

There are many reasons for that, and it is difficult to delineate the exact causes for that (urbanization, industrialization, feminism etc. spring to mind), yet one event seems crucial for understanding it.

When Greece joined the EU in 1981, it had a fertility rate of exactly 2.1; yet not even a decade later it declined down to 1.4.

It looks like the moderate wealth, prosperity and social liberalism that came with the EU also destroyed Greece demographically.

Knowing that the amount of Greeks born every year today is less than half the amount of Greeks born 60 years ago, is a very strange and uncomfortable feeling.

Simply put: not enough babies are being born.

Now of course, Greece is not the only country with these demographic problems; many other European (and some East Asian) countries also face abysmal fertility rates and shrinking populations.

Yet Greece’s case is especially worrying, given its other problems.

Radical consequences and demographic destiny

A stagnating, and even declining population essentially means that your economy cannot grow via consumption.

Other countries, even poor ones can have economic growth simply because of their growing consumer base, resulting out of a growing population with high birthrates.

Greek markets are shrinking, both dramatically in proportion to other (demographically growing) countries and even in itself.

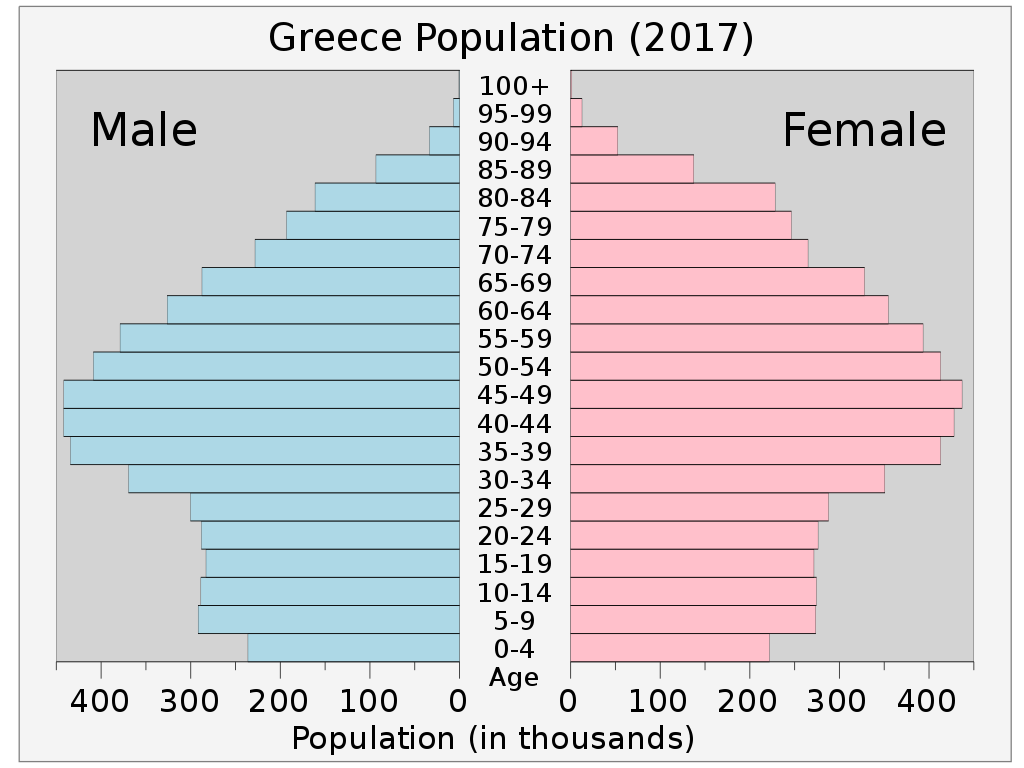

It also means a shrinking workforce, considering that nowadays roughly 20% of the Greek population is aged 65+, compared to only 11% in 1970.

If you add to the fact that many young Greeks, especially educated ones, are leaving the country for better economic opportunities, it seems even more disastrous.

To balance out this age shift, many Western European countries have relied on immigration to “replace” their elder natives, yet immigration raises many other questions concerning national identity, security, integration and assimilation.

Therefore it cannot be taken for granted and as a viable long term solution in a country like Greece.

Given the financial situation of Greece, the picture becomes even bleaker.

If an economy cannot grow via consumption, it has to grow via investment, which is a crucial topic considering Greek debt.

As I said before, Greece’s demographic problem has another facet.

Turkey has been Greece’s primary security threat and geopolitical rival for many decades now (to be fair in its entire existence, but let’s view it out of a post World War II perspective).

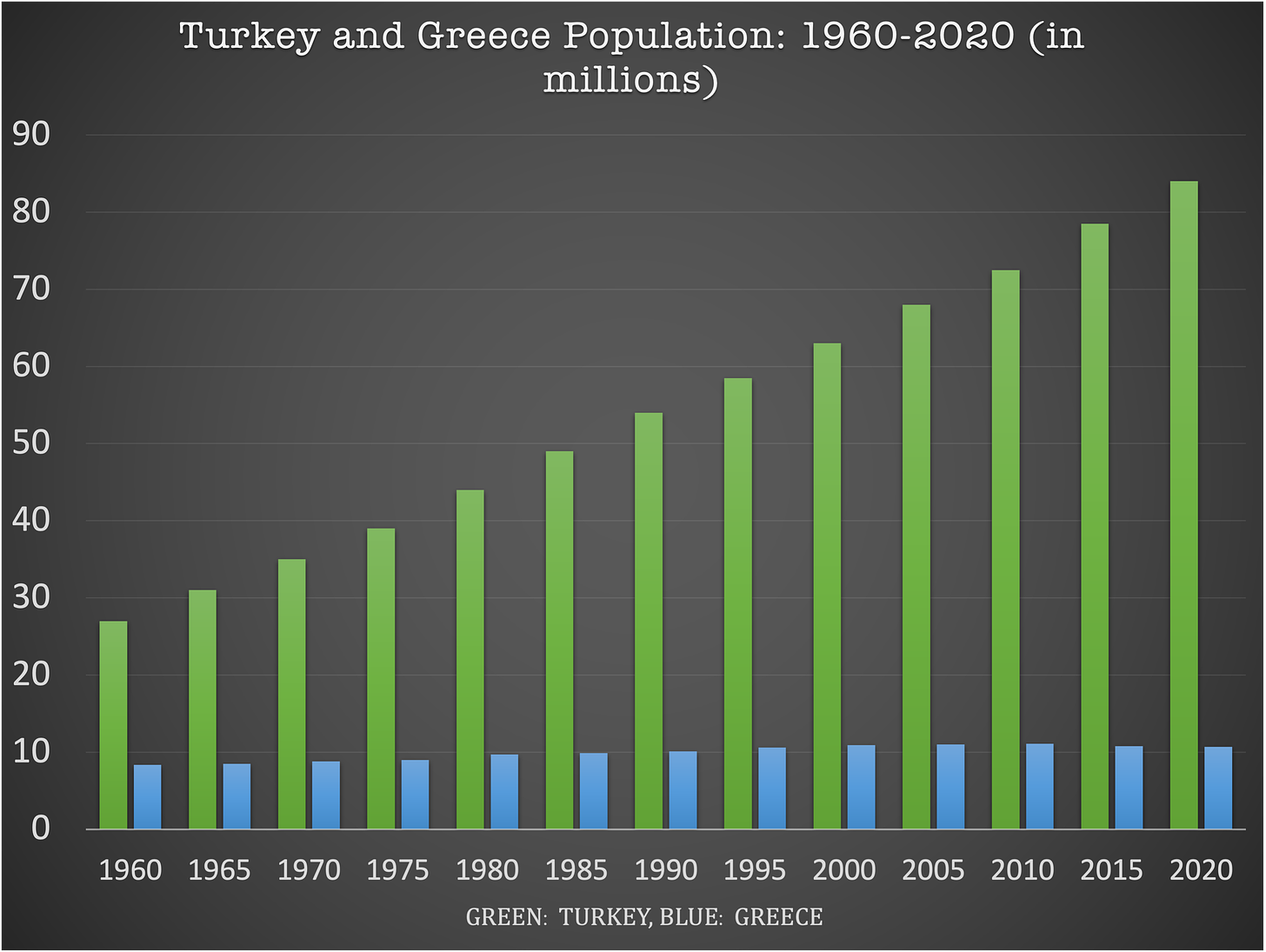

In the 1960s Turkey had a population roughly three times the size of Greece; but while the Greek population started stagnating, the Turkish population continued to grow every year and now is more than eight times the size of Greece.

This unfolding is very worrying out of all perspectives.

To give an illustration, during the Cyprus Invasion of 1974, Turkey had a population of 38 million, during the Imia Crisis of 1996 that had jumped to 60 million, and now it is nearing 85 million.

With this demographic advantage, it is easy for Turkey to build economic and military leverage over Greece.

And no economic or political solution will easily fix that.

While Turkey’s fertility rate has recently also dipped below the 2.1, it is going to be a long time until the population starts stagnating or declining; the country does have an admittedly very healthy demographic outlook.

Last year’s assault on the Greek border, in which Erdogan sent hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants to the Evros in an attempt of demographic warfare, reaches completely new and scary dimensions.

Such problems will only increase and multiply in the future given the current demographic prospects and developments.

One is seeing similar events unfold on the Greek islands and migrant hotspots, where (mostly) elderly islanders are overwhelmed with the amount of foreign men of fighting age arriving on their shores.

It's also interesting to keep in mind that such strategies of demographic warfare have a long tradition in Turkish intelligence operations; as the motto goes: “The Greeks aren’t having babies, so we’ll just send some hundred thousand Muslim migrants to finish them”.

The popular saying “demographics is destiny” doesn’t exist without a reason.

The truth is that out of all problems Greece is facing, this is the most important one as it determines the outcome of nearly all others.

The Greek government has started giving out baby bonuses to boost the birthrate, which is a positive step towards the right direction.

Yet one would need to look at the problem more closely and tackle it in all its different forms to accomplish long term goals.

Making one-income households economically viable so that the mother can stay home.

Promoting it more compelling culturally (such as rather traditional social values) and so on.

The recent developments in Hungary should serve as a blueprint.

Yet even without all the economic, military and social problems this demographic crisis bears as a consequence, it speaks to something much more fundamental at its heart: A population that refuses to reproduce itself is destined to die out.

The health and identity of a nation lies in its demographic renewal.