That we've broken their statues,

that we've driven them out of their temples,

doesn't mean at all that the gods are dead.- IONIAN, Constantine Cavafy

In 1962, Thomas Kuhn published his masterwork "The Structure of Scientific Revolutions", which presented the revolutionary idea that periodic and rather sudden “paradigm shifts” provide whole new ways of understanding things that we have never considered before. He also stated that there are often competing paradigms in circulation – irreconcilable accounts of reality with one account necessarily replacing its predecessor. Consider for example the radical ideas of the earth revolving around the sun, of equal rights for all human beings, or that humans evolved over millions of years and were not created in just six days.

Changing Times: Social Media Movements

We are obviously in such a moment today – with the climate crisis, the #MeToo movement, "Black Lives Matter" and other efforts to change institutional and social inequity and attitudes. We have been lurching toward this moment for years, but the pace has accelerated, and the tipping point, where one outmoded paradigm yields to another, was triggered by the slow, brutal public murder of George Perry Floyd Jr. – in Minneapolis, Minnesota on the 25th of May 2020. Then, the pandemic drove us indoors into isolation, fear, and a new way of working and interacting. At the beginning of the pandemic, the British actor and author Stephen Fry tweeted:

“OK. Until this thing is over, we’ve all got to be helpful, friendly and kind to each other, understood? Hatchets buried. Grievances forgotten. Disputes resolved. Feuds ended. Strangers smiled at. When the final whistle is blown, we can go back to be being mean and beastly. Agreed?”

Now, as we begin to re-emerge, vaccinated, into the community again, I don’t think we can be quite as “beastly” as before. Something has changed. The sight of a playground full of parents, grandparents, and children mingling together happily – if a bit hesitantly, now sparks more powerful emotions than before, as does the sight of an old man sitting alone on a park bench or a nurse in uniform taking the bus home from hospital. Introspection, gratitude, and generosity, taking root in surprising places, have begun to inform our thoughts and actions. Justice is back on the menu, too. The cry of “but it was all perfectly legal!” no longer ends a discussion. We are now forced — and entitled — to ask “But was it right? And what should we do now?”

As a consequence, everything is up for re-evaluation. Even the 200-year-old dispute over the Parthenon Sculptures has taken on new meaning, new urgency, and a whole new index of associations. For instance, the Parthenon is undergoing its own #MeToo moment as the concept of “Consent” has become an accepted metric for how we judge actions performed even centuries ago. “That was just how things were back then” is not good enough. Now we have to do better. Young people today are holding our feet to the fire on a whole range of issues. Trying to adapt to a new paradigm may be awkward and confusing, but it is also an opportunity to put our house in order, for which we should be grateful.

Pericles and the Parthenon: A Quick Review

There are literally thousands of descriptions, interpretations, laments and odes written about the Parthenon. It would probably take longer to read them all than it actually took to build the thing itself. But perhaps it would be helpful to insert here a brief review of the monument before we go dashing off into an exploration of the arguments and issues surrounding it.

In 490 BCE, the city-state of Athens defeated an invading Persian army led by their King Darius. Then, ten years later, it put together an alliance of other Greek city-states to defeat, once and for all, a massive new invasion led by Darius’s son Xerxes. Using the ensuing peace to consolidate this alliance into an empire, Athens also embarked on one of the most ambitious social experiments in history: Democracy.

After being named “strategos” (general) and elected to the highest civil office in Athens, the statesman Pericles introduced a number of social innovations that included subsidizing theatre admission for poor citizens and providing pay for jury duty and other civil service. He also launched an ambitious program of public works centering on the Acropolis, whose earlier temples had been destroyed by the Persians. Pericles, understanding that Athens’ hard-won democracy was special and deserving of celebration, constantly reminded his fellow citizens of the value of the peace they had earned, assuring them: “Be absolutely certain of this: that happiness depends on being free, and freedom depends on being courageous.” But rather than turning Athens into a military state, he focused on transforming it into a model of the good life through education, the arts, and full participation by the citizens in every aspect of public affairs. To symbolize the power and uniqueness of democratic Athens, he convinced the citizens (and other not-quite-so-thrilled alliance members) to finance the construction of the Parthenon and other buildings on the Acropolis.

For the Athenians of Pericles’ time, the Persian invasion of Greece and the sacking of the Acropolis was still deeply traumatic. Constructing the Parthenon was therefore their chance to “build back better” and to declare to themselves and others what it was that Athens stood for and could accomplish. What they didn’t realize was that this moment, which they would immortalize in the Parthenon, was the very peak of their culture, and that plague and war with Sparta would soon clip the wings of empire and even endanger democracy itself. There was still much to admire in post-Periclean Athens, as there is today, but the convergence of creative forces and resources needed to produce the Parthenon was perhaps unique in human history.

Dedicated to the city’s patron goddess Athena, the Parthenon was built using cutting-edge concepts of mathematics, engineering, and aesthetics. It was planned to embody everything that the Athenian people held most dear: truth, beauty, freedom. Using 20,000 tons of gleaming white marble quarried from Mount Pendelicon to the north, the temple was completed in just fifteen years, from 447 to 432 BCE, including the six years required to create its incomparable sculptural decoration. Designed by the sculptor Phidias, who oversaw the architects Iktinos and Callicrates, the Parthenon was decorated with statues and a frieze carved by the era’s greatest artists. However, these sculptures were not simply decorative; they told the story of the Greek people’s kinship with the gods and heroes of mythology. They depicted the founding of the city, celebrated the success of Athenian democracy and civic culture and dramatized the struggle against the forces of darkness and chaos. Possibly unique among buildings in the world, the Parthenon brought together in one living entity all the major forms of art and technology: architecture + sculpture (inseparable until Lord Elgin), mathematics, painting, mythology (metopes and pediments), storytelling (the frieze), politics, religion, drama, civics – and even music by reference. The Parthenon had it all.

Back to the Future: The Present

Today, the first time one sees the Parthenon in person as a student or tourist, it is quite frankly hard to digest. Very little in our daily lives can prepare us for such an encounter. However, it pays to persist and to try to observe the Acropolis at different times of day and night and from different vantage points: from the Hill of Philopappos or the Pnyx, from the top of Mount Lycabettus, from the Parthenon Gallery of the Acropolis Museum, or from the rooftop terrace of a hotel. Then, the temple will start to grow on us, make sense, come increasingly alive, and remind us of our own first encounter with the sublime.

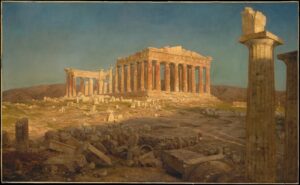

Image: "Parthenon" 1871 by Frederic Edwin Church, The Met, NYC

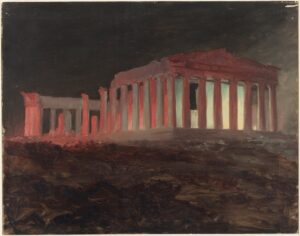

Although the temple is considered the ultimate expression of the “Doric” style, elegant in its direct simplicity, the fun begins when we realize that there really isn’t a straight line in the whole affair. All the elements, especially those wonderful Doric columns, have been tempered and tapered, accentuating the entire structure’s rhythmic connection between math and music and the way its mood changes with the changing light of day. Pendelic marble, renowned for its purity and brilliance, is also remarkable for its iron content. Over the centuries, this iron has gradually reacted to the oxygen in the air and given the exposed surfaces a honey-like glow intensified by dawn, sunset, and moonlight (or fireworks), as in the famous paintings by Frederic Edwin Church. The late-afternoon painting (1871) on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is perhaps worth a visit all by itself. Church’s other Parthenon, also shown here, is a nighttime oil sketch which captures the effects of both moonlight and a fireworks display which took place during his two-week stay Athens in 1869. The painter was prepared for his encounter with the Parthenon by the writings of the German historian Johann Winckelmann, whose conclusion, “The general and most distinctive characteristics of the Greek masterpieces are, finally, a noble simplicity and a quiet grandeur,” sums up in words what Church expressed so powerfully in paint.

Image: Parthenon (1869) Oil sketch by Frederic Edwin Church, Cooper Hewitt Museum, NY

For the Greeks, the Parthenon, from its construction until today, has formed a central part of their identity, representing their heritage and culture in a continuity shared with the remarkable Greek language. After the Greek War of Independence, which began in 1821 and took nine long years of fighting to conclude, the Greek General Ioannis Makriyannis taught himself to read and write in order to pen his memoirs “For the Freedom of the Country”. Referring to the ancient monuments and statues, he declared: “These are what we fought for.” Echoing these sentiments several years later, in 1837, Iakovos Rizos Neroulos (the founder and first President of the Greek Archaeological Society) said: “These stones are more precious than rubies or agates. It is to these stones that we owe our rebirth as a nation.”

For over a century, Greeks have been toiling with dedication to repair some of the damage inflicted on the Parthenon by General Morosini and Lord Elgin. This dedication shows that the Parthenon and its scattered sculptures have always held a special meaning for the Greek people – and also for anyone else who has tried to enter into the spirit of the remarkable Greek culture. The British themselves, having played a key role in helping Greece gain her independence, understand this and over the years have often sought to find a solution to the “Elgin problem”.

In order to better understand why the Parthenon is a symbol of controversy as well as culture, we will take a quick look next week at Lord Elgin’s actions while he was serving as Britain’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire and will explore as well the Ottomans’ attitudes, laws, and traditions regarding the protection of cultural heritage. After all, Elgin had their blessing to remove the sculptures from the Parthenon and ship them off to England, didn’t he? Or did he?

NEXT WEEK'S COLUMN: “We focus on the 'crime and the crime scene' as Greece lived under the Ottomon Empire.

ABOUT THE PARTHENON REPORT | DON MORGAN NIELSEN:

In this bicentennial year since the birth of the modern Greek State, of both pandemic and celebration, Greek City Times is proud to introduce readers to a weekly column by Don Morgan Nielsen to discuss developments in the context of history, politics and culture concerning the 200-year-old effort to bring the Parthenon Sculptures back to Athens.

Classicist, Olympian and strategic advisor, Don Morgan Nielsen is currently working with an international team of colleagues to support Greece’s efforts to repatriate the Parthenon Sculptures.

Click here to read ALL EDITIONS of The Parthenon Report by Don Morgan Nielsen

Feature Image : Copyright Nick Bourdaniotis | Bourdo Photography