It had always been my hope to meet Mikis Theodorakis, humanitarian and composer of the famous Zorba’s Dance and the hauntingly beautiful Mauthausen Cycle, but sadly that is no longer possible with his death Thursday, September 2, 2021, at ninety-six. This desire began in 1968. I was in the US Navy, aboard a ship whose first Mediterranean port of call was the Greek city of Athens, where I, with several hungry shipmates, discovered a taverna in the Plaka, the old part of the city, a warren of shops and small family run establishments. We walked through the open door from the narrow stone street into a small, humble establishment with maybe a dozen tables. A waiter, who looked like he had stepped down from one of the sepia toned photos that hung randomly on the white-washed walls, ushered us to a table in the back. Bushy moustache, white half-apron wrapped around his waist, he did his best to make us feel welcome by using the little English he knew.

Many of the dishes were prepared ahead and displayed behind glass in front of the open kitchen. Dolmades, stuffed grape leaves filled with rice and ground beef; moussaka, an eggplant dish with ground lamb or beef; pastitsio, a lasagna type casserole layered with tubular pasta and beef ragu, and topped with béchamel sauce; sautéed green beans with garlic cloves and tomatoes and taramosalata, a creamy Greek appetiser made with fish roe and eaten with flat bread. My taste buds buzzed and my mouth watered. I was very familiar with the grape leaves, having grown up in a Lebanese family, but the rest were new culinary adventures. We let the waiter bring us various plates of his selection. He didn’t disappoint.

While we ate, a trio of acoustic musicians played melodies that opened my musical mind. They were earthy and plaintive – guitar, bass and bouzouki trading the solo while the other played counter melodies to the lead. Music born from the rebetiko tradition, Greek folk music.

My good friend Al Lohmann said it for us all under his bushy moustache, “If I die tonight, this has been enough.”

Zorba came to mind, and since it was the only Greek song I knew, I asked the trio, “Can you play Zorba?” There was no response, so I asked again, “Zorba?”

The guitarist shook his head no.

“You don’t know Zorba?”

He looked to the waiter who came over to our table to explain why they wouldn’t be playing Zorba.

It was against the law!

Against the law?

It turned out the music of Zorba composer, Mikis Theodorakis, was forbidden to be played or listened to in Greece. “I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore” came to mind.

Why, I wanted to know? Why would a song be outlawed? Okay, somebody now had my attention. Who, I didn’t know. But, I wanted to hear his music and I wanted to know more about the man, the composer.

***

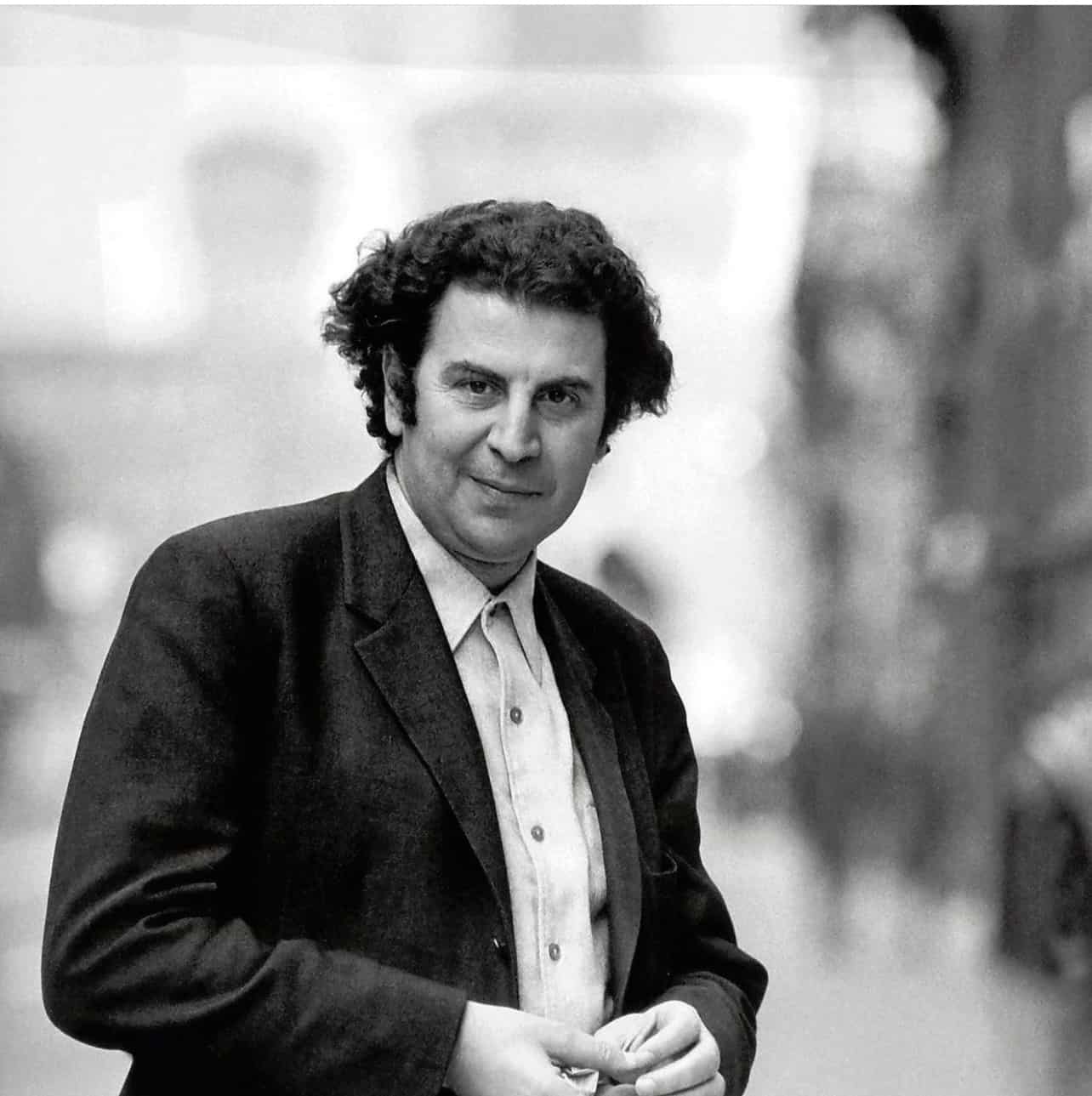

I learned Mikis Theodorakis, the tall, bushy haired, then 42-year old famously popular composer and activist, had spoken out once too often against the ruling military junta. Also known as The Regime of the Colonels — the somebody and the who — it was an untenable position, both for him and the junta. So, in 1967, shortly after the Colonels seized power, they arrested and tortured him, and banned his music and writings.

Theodorakis spent time under house arrest in the mountains far from his Athens home. Then, when the junta realised he was a bird who would not stop singing they interned him in the concentration camp, Oropos, on the island of Macronisos.

As for myself, other than being unable to hear or access anything Theodorakis, I did not sense the civil restrictions and fear under which the Greeks were living.

***

Several years after my first visit, I returned to Greece – to its food, its sun, its people and its music. And, to understand why Theodorakis, who clearly was as tough and resilient as the fictitious Zorba, the character about whom he wrote the song, and identifiable just from its first two notes, why he was so important to the Greek people. So, in 1971, I flew to Athens, as a civilian carrying just a back pack and my guitar.

On my first night there, I sought out the taverna I had come to love during my Navy visits. As I approached the location, I became confused. I didn’t see it. It wasn’t there.

Did I have the wrong address? No, I was sure I was in the right location.

Instead of walking into a place for which I had great affection, one that offered a feeling of family and hospitality, I was standing in front of a disco I found sad and tasteless, and, in my opinion, incongruous with the culture and tradition of the Plaka.

My taverna had closed since I was last there. All the warmth surrounding the memories of my shipmates and me gathered round a table savouring various Greek dishes, flavours new and exotic, drinking Grecian wines, retsina and beer, and on our ship’s return in the late Fall, even eating turkey “because it’s your Thanksgiving”, and listening to the wonderful folk melodies played by “our” trio… all this disappeared. I was frozen in my steps. I stood there deflated, feeling adrift and very alone. My anchor had come loose and my ship had sailed away.

I continued on, hoping to find a place that could replicate “my” taverna’s good food and music. But, all I found was a small restaurant that had recorded music, hoping to appease the tourists with some semblance of the Greek experience, about which they all fantasise.

“Zorba? Theodorakis?”

A quick shake of the head. No!

***

In the next couple of days, I connected with two young women from Canada and Switzerland, and ferried out to the sun-drenched island of Skiathos. There I met Yannis, a Greek guitarist and his wife Marie. Yannis and I played music during much of the week we were there, each time I asking him for a song by Theodorakis. And each time, he politely refusing. They were uncomfortable even speaking his name in public.

Other Greek composers like Manos Hadjidakis were very popular, but none elicited the responses Theodorakis inspired. He was the only one who dared defy the Germans in WW II and the junta during its reign. And, the only one for whom Greeks would risk their own lives. Like the woman who, as my research revealed, would swim out into the sea at night just to sing his songs. Or, the man who blasted Theodorakis’s music from his apartment balcony until the police came, trashed his speakers and arrested him. Even Theodorakis continued to put himself in danger; after he had been released from house arrest, he couldn’t resist poking his finger in the eye of the junta by playing his music one night to an excited crowd in the Plaka, resulting in his re-arrest. All shared while we were swimming in a secluded cove.

***

The week went by faster than I wanted with every passing day bringing something I’d never experienced before. The last day broke dark and dreary with a light rain falling over the island. It was the beginning of September and I could feel autumn in the air. A familiar melancholy took up residence in me as often happened at that time of year. The changing of the seasons. My friends and I rushed to catch the morning ferry back to Athens only to watch it leaving as we arrived at the landing. Standing nearby were Yannis and his family.

He suggested we go back to the house where they’d been staying. We would wait out the rain until the afternoon and only other ferry back to the mainland. So, we climbed the narrow, wet streets of Skiathos, and made our way above the waterfront, sun-bleached stucco houses on either side, their rain-soaked window boxes spilling over with the last blush of colourful, summer flowers. The occasional resident sitting in their window watching us pass by, unsmiling, sun-etched faces locked in their memories.

We arrived at a small stone cottage, owned by an elderly woman who rented a room to tourists. Unlike Yanni and Marie, she spoke no English. She didn’t need to. Her kind, toothless smile spoke for her. The years had carved themselves into the woman’s face, and I couldn’t help think this ilikiomeni, this old woman, must have compelling stories to tell, some joyful, some, perhaps still raw and hurting.

Little goats peeked in an open window as she welcomed me and my companions to her home and brought out mezza – simple, small plates of food, for us to eat.

We had several hours to wait, so we did what we’d been doing during the week; we sang and played, exchanging songs, both Greek and American. And, of course, as I had all week, I asked Yannis if he would play a song by Theodorakis. Rather than say no immediately, he looked over at his wife. Their eyes locked. I could almost feel them mentally ticking off the charges that could be brought against them for violating the ban. Then, a slight nod — Marie to Yannis.

“Okay.”

I wasn’t prepared for what happened next. The old woman drew the simple white, cotton curtains covering her glass-less windows, shuttered them, locked the door and lit a few candles, bringing light to the now darkened room.

Yannis began to sing. It was a soulful, heartbreaking melody under lyrics I didn’t need to understand.

I looked at Marie and the ilikiomeni. They were weeping.

Tears of joy? Tears of longing? Perhaps both. To me, they were tears that seemed to say, I am Greek and this is my music. And, I will play and listen to it. I looked around and saw my fellow travellers crying as well. For years afterward, I couldn’t tell this story without tearing up myself.

I would never forget that moment. It was then that I came to understand the power of music. And, how important Theodorakis is to the Greeks and would become to my life. He clearly reflects the spirit of the Greeks — be strong, and like my grandfather often told me, always have hope. Upon later reflection, it came to me that the song and candle lighting up the darkened room that day, joined the many other singular acts of courage to eventually bring light back to a dark, shadowy cheerless country.

I heard Theodorakis’s music in the junta’s Greece when it was forbidden. I now want to hear it in the people’s Greece where they are free to listen to whatever and whomever they want. And, while it may have not been Zorba I heard that day, sheltering from the rain, it may as well have been. I felt his presence, his strength and determination, his resilience in the song Yannis played.

In 1970, after intense pressure from an international community of celebrated artists, Mikis Theodorakis was released and exiled to Paris, living and working there until the junta’s fall on July 24th, 1974. He returned to Athens that day to a tumultuous and joyous reception, where he lived until he passed away this past week.

***

Several years ago, I sent Theodorakis an email, telling him about these events and received a reply requesting permission to publish my letter on his website, where it resides today. Though Mikis Theodorakis will live in his contributions to the world, and inspire countless lives in the future, for this writer he will always be remembered for offering me the courage to live my life truthfully and creatively.

And, while his time has passed and my chance to meet him as well, this hasn’t been about a destination, it’s been about a journey.

Mikis Theodorakis: Flags to fly at half-mast during three-day national mourning