That we've broken their statues,

that we've driven them out of their temples,

doesn't mean at all that the gods are dead.

- IONIAN, Constantine Cavafy

On October 4th of this very strange year, 2021, George Osborne, former Chancellor of the Exchequer and editor-in-chief of the London Evening Standard, took over from Sir Richard Lambert as the President of the British Museum’s Board of Trustees. In an article in the June 29 edition of The Financial Times entitled “George Osborne’s horrible histories at the British Museum”, the position of Chairman of the Museum’s Board of Trustees is described as: "a ceremonial role that mostly involves raising money and refusing to give the Greeks back the Elgin Marbles". Within the context of this job description, here is how Sir Richard Lambert, himself a former editor of The Financial Times (1991-2001), describes the Trustees’ number one priority and obligation:

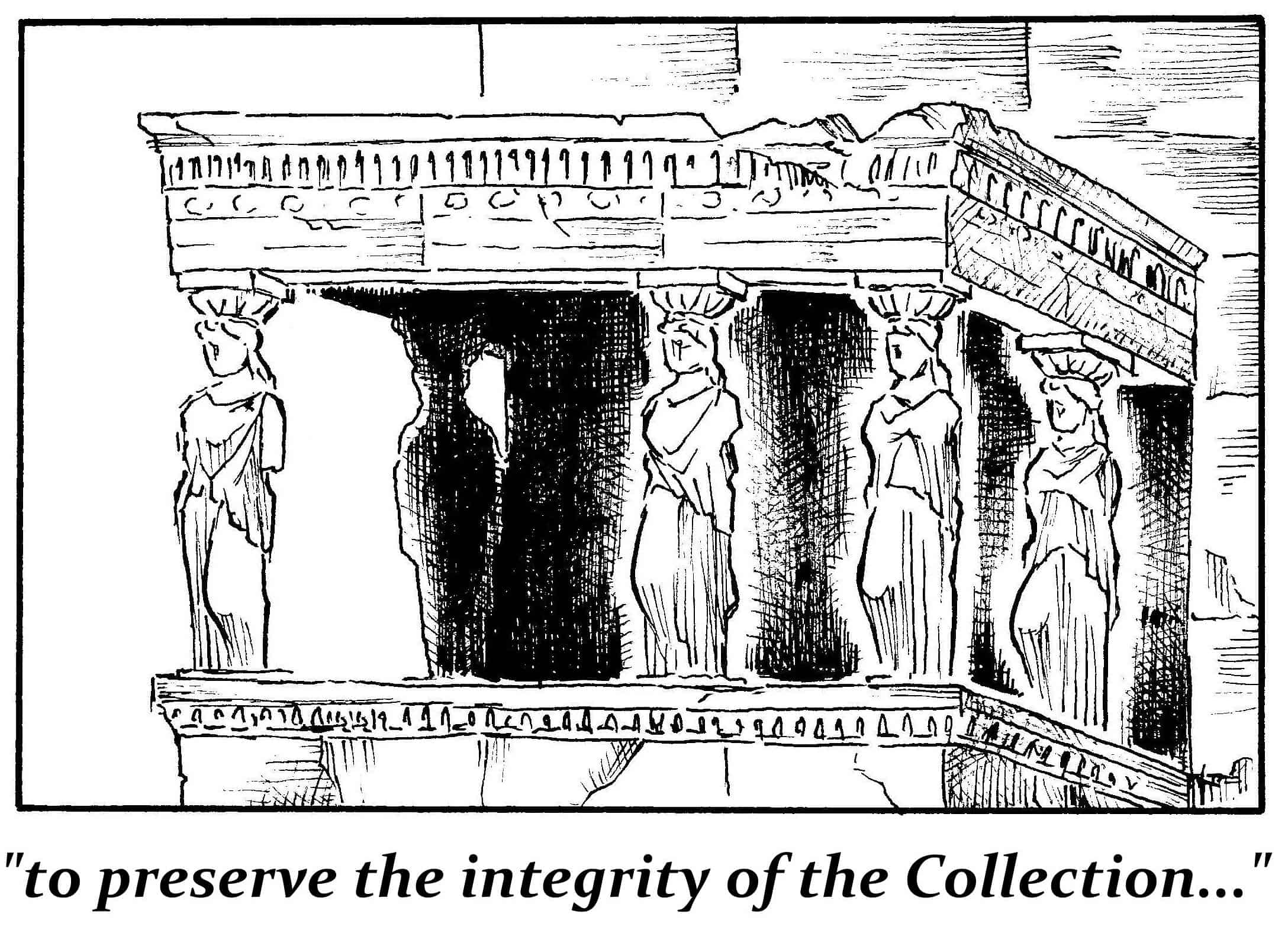

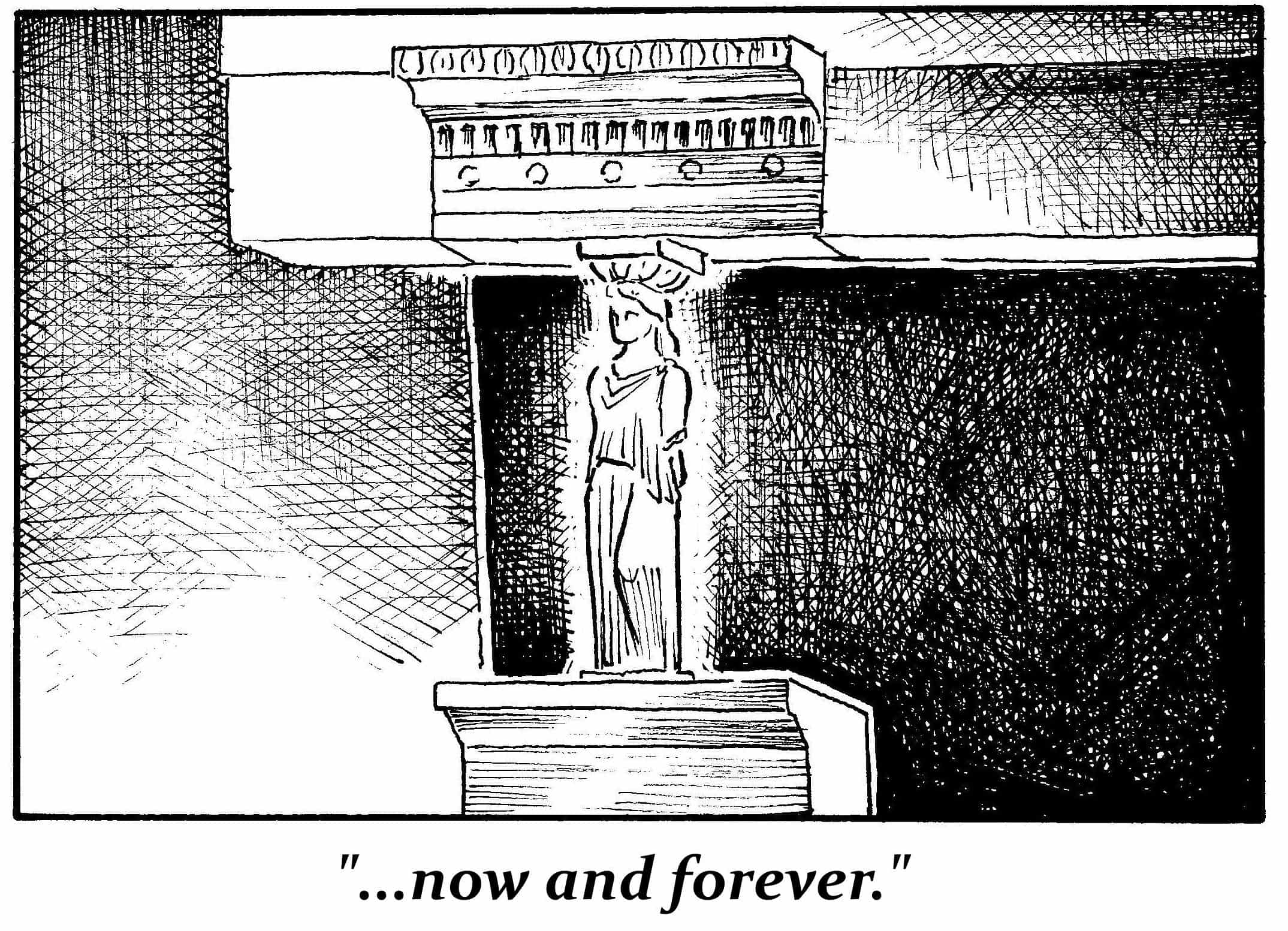

"It is our duty to preserve the integrity of the Collection, now and forever."

Strange choice of words – but before exploring the meaning and implications of Sir Richard’s statement and speculating as to whether or not George Osborne, as his successor, will hew to the same party line, let’s take a look at the Cambridge Dictionary definitions of the word “Integrity”:

- Being honest, with strong moral principles

- The quality of being whole and complete

Integrity #1: Being Honest

It seems that both aspects of the word are involved here, but let’s begin with the first and most common understanding of the word “integrity”, meaning “being honest”. In earlier columns, we have looked at Lord Elgin’s motives in removing the sculptures from the temples of the Acropolis, as described in his correspondence with the overseer of his collecting operations in Athens, Giovanni Battista Lusieri. Elgin had begun a major renovation of his mansion back in Scotland, Broomhall Manor, and wanted lots and lots of marble columns and valuable antiquities in order to turn Broomhall into a model of the newly fashionable Greek Revival style and “the grandest house in Scotland”. Just a few years later, however, in his explanation to the House of Commons Select Committee tasked with deciding whether or not to purchase these sculptures from him using public funds, Elgin claimed that his patriotic purpose in “rescuing” these imperiled antiquities from the “Mischievous Turks” was to preserve them for posterity and to elevate the fine arts in England. Having bought Elgin’s story along with the Sculptures themselves, Parliament had little choice but to pass along this acquisition tale to the British Museum as an “integral” part of the legacy of “the Elgin Marbles”. And from 1816 until today, the Museum has been adding to and improvising upon this tale, both with regard to the motives and legality of the Sculptures’ acquisition – and in its ever-evolving justifications for their retention. As in the Parthenon itself, there is not a single straight line in the Museum’s narrative, and, as a famous carpenter once said, “they have built their house upon the sand.”

“The readers of ‘RIVISTA’ are doubtless aware of the recent movement in England in favour of restoring to Greece the marbles which some 80 years ago were seized and removed from the Acropolis by Lord Elgin… It is to be borne in mind that it is not dignified in a great nation to reap profit from half-truths and half-rights; honesty is the best policy, and honesty in the case of the Elgin Marbles means restitution.” – from the only surviving published work in English by the poet Constantine Cavafy (1891)

Integrity #2: Being Whole and Complete

But when we come to the second meaning of “integrity”, “the quality of being whole and complete”, it is easier to see why the case of the Parthenon Sculptures is so singular and clear. As Frederic Harrison said in his article for the journal “Nineteenth Century”, the Sculptures “are not statues; they are integral parts of a unique building, the most famous in the world.” The Parthenon was conceived, designed and built as a single, multidimensional entity, whose structure and decoration were, until Lord Elgin, inseparable and integral to each other. The building was created to serve as a kind of 3-D map of the Greek story and culture, and the key to interpreting this map lay in its sculptural decoration: the frieze, metopes and sculptures of the pediments. The frieze, in particular, told its part of the story in a continuous loop that ran all the way around the temple. When Elgin dismantled much of the temple to remove the better (and best) part of this sculptural decoration, he also shattered this continuity and destroyed what remained of the Parthenon’s original structural and artistic integrity.

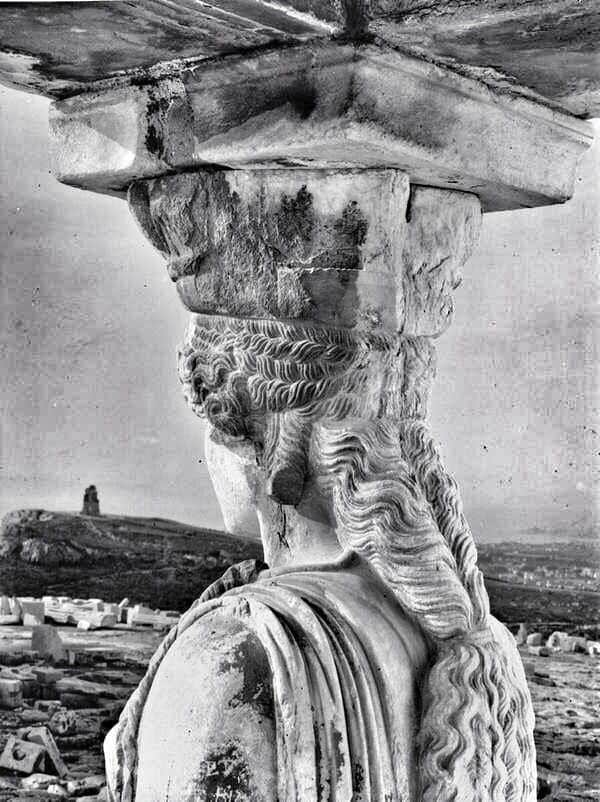

Original Integrity and the Sisterhood of the Caryatids

The same holds true for the Erechtheion, one of whose caryatids Elgin took back to London and another his men broke to pieces and left lying on the ground. This original integrity of the temples of the Acropolis, of the structure and sculptures working together as a whole, is the integrity we should be talking about – rather than the fabricated integrity of a collection made by breaking apart and removing key elements of other peoples’ national shrines and monuments. The Parthenon and the Erechtheion were collections too, in and of themselves. These collections had real integrity, in all senses of the word. First of all, the sculptures were integral to each other, and together they told a story. They were also integral to the structure and meaning of their respective temples, to the identity of the city of Athens and eventually to the independent nation of Greece itself. This integrity was original, organic and intentional. The multiplex compositions conceived by Pericles, Phidias and the artists and architects working under him told a public story and served a very public function. They should not be confused with the individual statues, some created by these same artists, which were meant to stand alone and were usually commissioned by and sold to private patrons or collectors. Looking at the caryatid standing alone in the British Museum today, one might think that this was the case here, of a sculpture meant to be bought and sold and moved about, but she was originally one of six sisters, who together held up the south portico (“The porch of the Maidens”) of one of the world’s most unusual temples – the Erechtheion. Folk legend has it that people living near the Acropolis can hear the remaining five caryatids crying out at night for their lost sister, a cry echoed by Athena’s own little owls (Athene noctua).

However, the dis-integration carried out by Lord Elgin 200 years ago, and the perpetuation of that dis-integration today, is something that can be largely corrected and set right. In 1941, in response to Tory MP Thelma Cazelet-Keir’s question to Prime Minister Winston Churchill about restoring the Sculptures to Greece – the British Government concluded that this was indeed feasible and even a good idea, so long as three conditions might be met: that a museum be built in Athens to properly protect and display the Sculptures; that the Greek Government defray any costs associated with their restitution; and that exact replicas be made to display in Bloomsbury. These conditions have since been met or agreed to, and plans are afoot to substantially up the ante within the context of a radically generous win-win solution. Nothing now stands in the way of doing the right thing and restoring integrity to this great work of art – and to the relations between Greece and Great Britain.

So, whenever a British Museum or Government official is tempted to use the word “integrity” while defending the continued separation of these Sculptures, half in London and half in the Acropolis Museum in Athens, they should stop and consider what they are really saying.

NEXT WEEK: Don Morgan Nielsen looks at the concept of “narrative” and the Sculptures’ role in a great story that was broken and interrupted by Elgin and remains broken and interrupted to this day. In this sense, the “narrative” of the Parthenon Sculptures is closely tied to their “integrity” – their original integrity.

ABOUT THE PARTHENON REPORT | DON MORGAN NIELSEN:

In this bicentennial year since the birth of the modern Greek State, of both pandemic and celebration, Greek City Times is proud to introduce readers to a weekly column by Don Morgan Nielsen to discuss developments in the context of history, politics and culture concerning the 200-year-old effort to bring the Parthenon Sculptures back to Athens.

Classicist, Olympian and strategic advisor, Don Morgan Nielsen is currently working with a growing international team to support Greece’s efforts to repatriate and reunify the Parthenon Sculptures.

Click here to read ALL EDITIONS of The Parthenon Report by Don Morgan Nielsen

Feature Image : Copyright Nick Bourdaniotis | Bourdo Photography