That we've broken their statues,

that we've driven them out of their temples,

doesn't mean at all that the gods are dead.- IONIAN, Constantine Cavafy

After two messy centuries of wars and revolutions of all kinds, the 21st Century arrived bearing promises of innovation, cooperation, healing and justice. Between 1960 and 2000, UN membership doubled; Nelson Mandela peacefully shepherded South Africa to democracy, and the world in general seemed to be trying to put its house in order.

One of the first tasks for newly liberated or newly democratic nations is symbolic in nature and involves reclaiming key elements of their cultural heritage which had “gone missing” during the dark times of colonial occupation or war. This project is far from complete, and pockets of resistance still remain, but museums are playing an increasingly important role in the dialogue between nations and setting an example of inclusion and justice in their communities. How they deal with indigenous peoples and minorities – and how they respond to requests for repatriation – to a great degree shape how they are seen as a force for education and moral leadership. Institutions which lead by example on these issues will find themselves on the right side of history, resolving problems that still linger from the past so that they can focus on the challenges of tomorrow.

By 2002, a growing clamour for the return of “problematic” cultural artefacts held by major western museums, including continued requests by Greece for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures, had reached migraine intensity. In order to provide relief from repatriation claims (without actually having to deal with them), the British Museum put together a coalition of 18 like-minded museums to launch an audacious branding and PR offensive under the title The Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums which states, among other things:

“We should recognize that objects acquired in earlier times must be viewed in the light of different sensitivities and values, reflective of that earlier era. The objects and monumental works that were installed decades and even centuries ago in museums throughout Europe and America were acquired under conditions that are not comparable with current ones. Over time, objects so acquired…have become part of the museums that have cared for them, and by extension part of the heritage of the nations which house them.”

Chutzpah and the Global Object

At the heart of this branding exercise lies the assertion that certain works of art, by virtue of their artistic excellence or historical significance, actually transcend their culture of origin and become “global objects”, which no longer can be said to belong to their source country but actually belong to the whole world – and, by extension, should be kept and displayed in a universal museum that can safeguard and display them for “all humanity”. Naturally, great works of art aspire to or attain a kind of universality, but a universal character shouldn’t be confused with an object’s identity and heritage – and certainly doesn’t justify its removal and retention by a stronger party with a sharp eye for beauty.

Furthermore, according to the Declaration, the Parthenon Sculptures, having been held in Bloomsbury for the past two hundred years, should no longer even be considered the cultural heritage of Greece – but of Britain. Cheeky, but clever.

Deracination by Declaration

On the basis of the Declaration, Hoa Hakananai’a, the Rosetta Stone and the Parthenon frieze are now integral parts of the British Museum and of Britain’s own heritage, best appreciated removed from their original context and placed together for comparison under the same (leaky) roof - in order, theoretically, to help the cosmopolitan visitor understand how different cultures express the human condition and to document the “march of civilisation”. These assertions are too vague and lofty to prove, refute or debate and mainly attempt to place the “universal museum” above the need for dialogue and beyond the range of standard criticism and accountability. To whom can we appeal this title of “universal”, with its implied universal holding rights? God and her angels? A committee of Apollo and the nine muses? The Pope? Isn’t universality like democracy in that it implies not only rights and privileges but universal accountability and responsibility as well? Rather than ending the debate as hoped, the Declaration opened a Pandora’s box of outrage, criticism and renewed scrutiny. After all, if you claim to speak for all humanity, you had better be sure that all humanity agrees with you.

Swift and Predictable Reactions

Hundreds of museums in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas were not amused by these museums’ self-appointment as custodians for the world’s artistic treasures. Geoffrey Lewis, then Chairman of ICOM’s (International Council of Museums) Ethics Committee declared that “the real purpose of the Declaration was to establish a higher degree of immunity from claims for the repatriation of objects from the collections of these museums. The presumption that a museum with universally defined objectives may be considered exempt from such demands is specious. The Declaration is a statement of self-interest made by a group representing some of the world's richest museums; they do not, as they imply, speak for the ‘international museum community’. The debate today is not about the desirability of ‘universal museums’ but about the ability of a people to present their cultural heritage in their own territory.” The general consensus among the international museum community was that the British Museum was fighting to protect its own heritage, not the world’s. The Declaration was felt to be an unhelpful display of arrogance at a time when most museums were trying to become more open to dialogue with source nations and their own communities, more focused on listening than preaching.

Ten years after publication of the Declaration, another forum for the world community issued its own response. The 2012 session of the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted Resolution A/RES/67/80, titled “Return or restitution of cultural property to the country of origin”. The resolution was co-sponsored by 98 member states including Canada, Italy, Mexico, Russia, Spain, and the US. Additionally, a number of these states have complained in response to the Declaration’s claim of universal access that even their citizens wealthy enough to travel abroad are denied access to the most important examples of their own cultural heritage because the UK Home Office disproportionately refuses requests for visitor visas from African countries, the Indian subcontinent, Cuba, Vietnam, Fiji and Thailand – even before the pandemic wreaked havoc on global travel.

Battle of the Books

Such was the outrage at the Declaration’s hubris that even its most eloquent apologist, James Cuno, CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust and author of “Who Owns Antiquity?” stopped referring to “universal” museums and began using the word “encyclopedic” in an effort to claim direct linear descent from the Enlightenment and the Encyclopédie edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert (whose modest aim was "to change the way people think and for people to be able to inform themselves and to know things.”) Springing to the defense of the British Museum’s retention of the Parthenon Sculptures and attacking the efforts of the “narrowly nationalistic” institutions trying to reclaim their countries’ most important antiquities, Cuno concludes that “Antiquities are the cultural property of all humankind, evidence of the world’s ancient past and not that of a particular modern nation. They comprise antiquity, and antiquity knows no borders.”

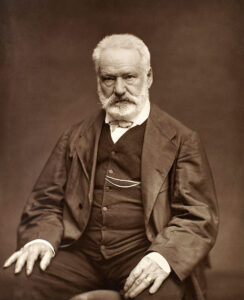

Cuno’s books are elegantly written, with well dressed arguments from the realm of art and aesthetics where he is an acknowledged master, but he misses a vital point, made here by Victor Hugo, on the distinction between the possession of an object and its appreciation, between its use and its beauty – and he entirely ignores the perspective of those whose ancestors created these masterpieces.

“There are two things about a building: its use and its beauty. Its use belongs to its owner; its beauty belongs to the whole world, to you, to me, to us all.”

–Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885)

“Who Owns History?” by Geoffrey Robertson QC, renowned Human Rights barrister and former UN appeals judge, sports a similar title but presents a diametrically dissimilar conclusion. With the clarity and precision of a great jurist and the courtroom tenacity of a modern-day Cicero or Clarence Darrow, Robertson is a worthy foil to the universalists’ lofty claims. In direct response to Cuno’s description of universal, encyclopedic museums as “liberal, cosmopolitan institutions which encourage identification with others in the world and a shared sense of being human, of having in every meaningful way a common history, with a common future” – Robertson says the following:

“Cuno does not understand that this future might be better if museums took a moral approach to it (the question of repatriation), with a common commitment to honour human rights, or that ‘identification with others in the world’ might involve giving back some of their stolen property.”

What Is Truly Universal?

Doing the right thing does not need eloquent apologists or grandiose declarations, and yet it is the most universal concept of all. It is as simple and solid as rock, on which a better future might be built. Here is what Steven M. Dettelbach, U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Ohio, had to say in January 2013 at a ceremony to mark the return to Italy of a looted vase that had been one of the most prized objects in the Toledo Museum of Art:

"I want every museum, every business and every school child here in Toledo to see and understand that today is about living up to a very basic principle. When you find out that something is not rightfully yours – no matter how special, no matter how beautiful or no matter how costly that thing might be – you give it back".

NEXT WEEK: Don Morgan Nielsen will conduct a brief, final summary of the main arguments for and against the return of the Parthenon Sculptures.

ABOUT THE PARTHENON REPORT | DON MORGAN NIELSEN:

In this bicentennial year since the birth of the modern Greek State, of both pandemic and celebration, Greek City Times is proud to introduce readers to a weekly column by Don Morgan Nielsen to discuss developments in the context of history, politics and culture concerning the 200-year-old effort to bring the Parthenon Sculptures back to Athens.

Classicist, Olympian and strategic advisor, Don Morgan Nielsen is currently working with a growing international team to support Greece’s efforts to repatriate and reunify the Parthenon Sculptures.

Featured Image: Copyright Nick Bourdaniotis | Bourdo Photography

Click here to read ALL EDITIONS of The Parthenon Report by Don Morgan Nielsen