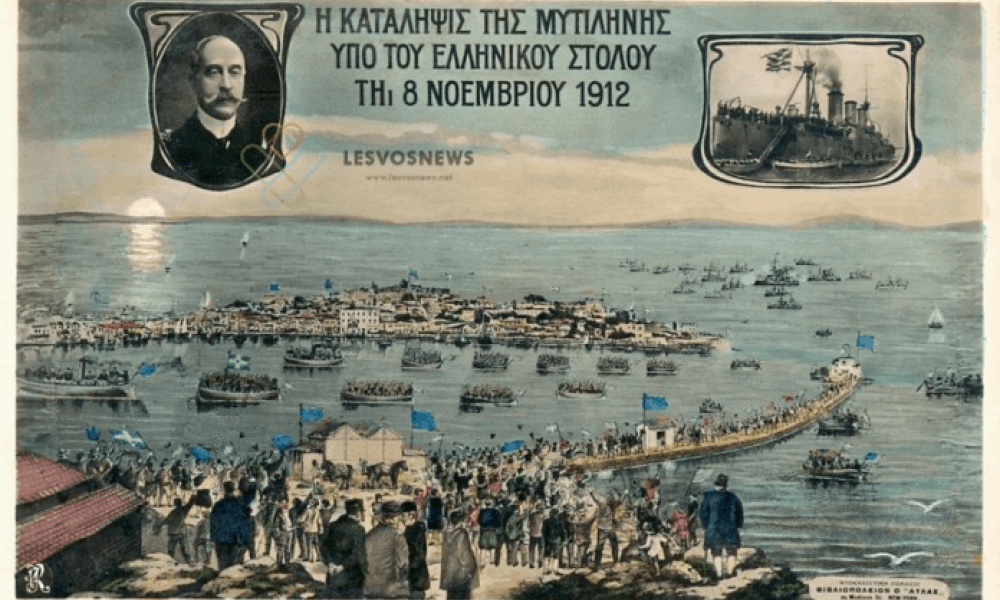

The Greek fleet, led by Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis, started from the bay of Moudros in Lemnos on the night of November 7 and anchored in the early hours of November 8, 1912 outside the port of Mytilene in Lesvos.

Among the Greek ships, the flagship of the fleet was the famous Georgios Averoff battleship who on its own liberated several Greek islands from the clutches of the Ottomans.

After the delivery of Koundouriotis' ultimatum to the Ottoman authorities of the island, with which the immediate surrender of the city was requested, a meeting was held between the Ottoman authorities and the Christian and Muslim dignitaries of Mytilene.

At this meeting it was decided to withdraw the small Ottoman armed forces inside the island and to occupy Mytilene without bloodshed in order to avoid the unnecessary bloodshed of the unarmed population.

The disembarkation of the Greek Marines and sailors began at 12:30 pm, under frantic festivities that took place in the so-called Petroskala, which was located at the site of today's Customs Building.

A eulogy was held in the metropolitan church of Agios Athanasios, in which the Metropolitan of Mytilene, Cyril, officiated, chanting "Christ is Risen" together with all those present.

The Plomari Militia

Immediately, with their announcement, the Greek authorities declared the union of Lesvos with Greece and declared equality for all the inhabitants, Christians and Muslims.

One of the first measures of the Greek administration was the issuance of a commemorative series of stamps.

The issue was marked with the Ottoman postage stamps confiscated with the phrase: "Greek Occupation of Mytilene".

The word "occupation" signified the temporary nature of Lesvos' integration into Greece, since the international treaty, which finally ratified this integration, was signed 11 years later, in 1923 with the Treaty of Lausanne.

However, the fate of the two islands of the Northeast Aegean, namely Imvros and Tenedos, were different with the above treaty as they were awarded to Turkey.

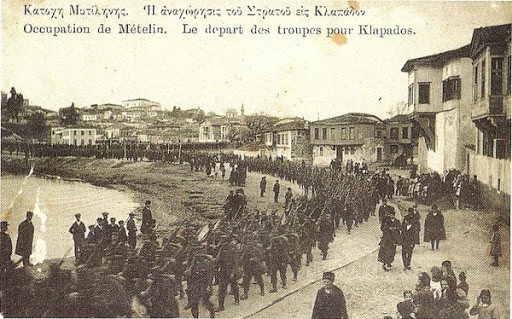

The number of Greek forces that landed on Lesvos not exceed 1,600 men. Because the Ottoman army numbered 1,500-2,000 men, it was decided not to make the final clash before reinforcements and ammunition arrived.

When the Greek army landed in Lesvos on November 8, 1912, several Christian patriots were put at the disposal of the Greek army, which equipped them with the aim of using them as a militia in the villages and as a counterweight to the Muslim guerrilla corps.

Thus, acts of terrorism against the civilian population were not lacking either by the Christians or by the Muslim insurgents in the areas of their action, with the result that an elusive countryside experienced moments of barbarism.

For this reason, the Greek authorities demanded the disarmament of the Christian guerrilla corps and punished several militants who took the lead in incidents against the civilian Muslim population.

The Ottoman regular military forces were fortified in their camp in Klapados, a Muslim village that no longer exists today and was located in the wider region of Lafiona.

However, the Christian inhabitants of the still Turkish-occupied part of the island had no doubt about the final outcome of the battle.

The Greek army had been significantly reinforced by about 1,500 men and many local volunteers. The main body of the volunteers was the famous Lesvian battalion which consisted of 210 Lesvian immigrants who had come returned from America to help liberate their homeland.

After the arrival of the coveted reinforcements at the end of November, the Greek army marched towards the fortified Ottoman camp in Klapados.

The Ottoman camp of Klapados did not withstand a long offensive by the Greek army, which began on December 6 and was accompanied by targeted artillery fire.

The bombing of the camp was complemented by amazingly accurate shots fired by Greek warships off the coast of Petra.

The surrender Ottoman army finally signed the surrender of Lesvos on the morning of December 8, 1912 at the Petsofas hill, southeast of Klapados.