That we've broken their statues,

that we've driven them out of their temples,

doesn't mean at all that the gods are dead.- IONIAN, Constantine Cavafy

This week’s column takes its title from a remarkable book by British writer, war-hero and master story-teller Patrick Leigh Fermor, who taught me crucial lessons in hospitality at his home in Kardamyli, Greece when I was a young teacher in Athens exploring the Peloponnese during school holidays in an old Russian jeep filled with books and with a large Maine Coon cat named Livestock in the passenger seat.

During a dozen visits over several years, the talk spilled laterally in all directions but often circled back to the subject of gift-giving, generosity and the Greek tradition of “philoxenia” or “guest-friendship”.

Fermor’s main thesis, always demonstrated with flair, was that the custom of giving and sharing, opening one’s heart and home to strangers and guests, was a central concept of ancient Greek culture. You were expected to welcome travelers into your home – for they could be gods in disguise, as in the famous myth of Baucis and Philemon depicted by Rubens above. A proper welcome included presenting travelers with a meal, a place to rest and often gifts – and only after they had eaten and drunk their fill would they be asked to tell their story. When the code of hospitality was violated (as when Trojan prince Paris ran off with Helen, the wife of his Greek host), war ensued, and the delicate fabric of social ties and relationships unraveled. However, the spirit of generosity, magnanimity and ritual gift-giving that had created such ties could also recreate or repair them and was the key to both domestic and foreign relations. Without the codes and rituals of hospitality, however, only the laws of the jungle remain, with the weak at the mercy of the strong.

The modern museum is learning this secret of hospitality as well, opening its doors to a wider public, listening instead of preaching, and even employing the art of giving to create new and lasting ties with source countries. Let’s look at a few examples of how museums have been using the return of important artifacts to build relationships for the future.

In 1995, delegates from the Lakota Sioux nation approached Glasgow Museums to request the return of a Ghost Dance Shirt – an important historical artifact that played a key role in their most sacred tribal ritual. Their request was refused, with the Museum citing legal ownership of the shirt. Glasgow City Council, however, set up a working group to examine the case more thoroughly; a public hearing was held in which Museum and tribal representatives presented their views, and the Museum’s board of directors decided that, while under no legal obligation to return the shirt, other values might be more important than possession. Both City Council members and the public voiced their support for the return, and the Ghost Dance Shirt was repatriated in 1999 in the form of a gift to the Lakota Sioux tribe from the people of Glasgow. But the story didn’t end there and, in fact, became more interesting. Lakota artists made a replica shirt, which they presented to the Museum and which is now on display with its full history – including the story of its return. More important, a relationship with the tribe was established that continues to this day, with great public interest, support and participation.

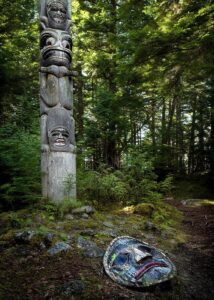

A totem pole comes home

Another tale of return more closely resembles the case of the Parthenon Sculptures and involves a totem pole created by the Haisla First Nation in British Columbia, Canada. Totem poles, like the Parthenon Sculptures, tell a story that is important to the tribe, using powerful images that have mythical, spiritual and historical significance. In the 1870s, Olaf Hansson, a Swedish diplomat stationed in Canada, requested permission from the federal authorities to take a native totem pole back to Sweden, and permission was duly granted. As with the removal of the Parthenon’s sculptures from Athens, the removal of the totem pole was made without the consent of the native community and was a “source of grief for the people of the Haisla Nation”, according to tribal elders. After years of discussion, however, Sweden’s Museum of Ethnography returned the pole to the Haisla people as a gift, and carvers from the tribe traveled to Sweden to create another pole for the Museum and to engage with the schools and local artists in a series of exchanges that has enriched both communities. At the dedication ceremony for the new totem pole in 2006, the Swedish Minister of Culture noted that this experience “has given us new friends – as well as cause to consider the importance of respect and cooperation in our dealing with one another in the present day and age.”

While critics may scoff at the example of “small museums returning minor artefacts”, none of the returns and exchanges currently taking place around the world are considered “minor” by the source communities which are welcoming home vital parts of their heritage – often with joy and ceremonies that rival the return of the prodigal son. Moreover, those museums which have treated source communities with understanding and magnanimity have shared the fatted calf as special guests at an ongoing feast of cultural exchange.

Such repatriations hold the power to heal wounds that major museums seldom fully understand. When Emmanuel Macron announced his commitment to return much of Africa’s cultural heritage, Prince Kum’a Ndumbe III of Cameroon’s Duala people, who have been separated from their most important cultural artefacts for nearly 100 years, said: “This is not just about the return of African art. When someone has stolen your soul, it is difficult to survive as a people.” The Prince considers Macron’s gesture “a huge step toward healing the wounds of Africa.”

Some of the world’s largest and greatest museums are now rising to the challenge as well, among them New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (“the Met”), which elected to return six of its most prized objects, including the famed “Sarpedon” or “Euphronios” Krater to Italy in exchange for long-term loans of a greater number of fine antiquities – and a far closer working relationship with that country. The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Republic of Italy Agreement of February 21, 2006 is now considered a landmark example of a win-win solution. Philippe de Montebello, the Director of the Museum at the time, praised the arrangement as evidence of Italian generosity, emphasizing that more works were loaned by Italy than the museum returned, and that new doors of exchange and opportunity had opened in the process. Even the most cynical New York journalists concurred. This agreement offered valuable insights into the process and value of repatriation and led many institutions to reevaluate their concepts of ownership. It may also point to a future where permanent collections are somewhat de-emphasized in favor of sharing rather than simply possessing, and where relationships, rather than objects, become the focus of museum policy.

Listening and Learning

In a similar action under Director Thomas P. Campbell (2009-2017), the Met repatriated several important artefacts to Cambodia and is currently preparing to return even more. In exchange, the Museum has received dozens of statues and other art work for special exhibitions and has established a working relationship with the country, which is still in the process of healing its wounds and building its institutions after years of devastating civil war in the 1970s. The Museum’s proactive and collaborative stance has put it on the right side of history and enabled the Met to develop close ties with this important source nation while avoiding a widening scandal over art looted from Khmer temples during the Cambodian Civil War. At a recent press conference on new efforts to recover looted art, the Cambodian Minister of Culture Phoeurng Sackona declared: “These are items that have a soul, and it’s very important for them to be home to help restore the Khmer culture. We want to write the history of every statue that was taken – for the true benefit of humanity.” The Met is listening carefully to such voices from Asia and Africa because it has learned that among the many different and often competing values of an object, its value as a bridge to another culture and a new relationship is perhaps its greatest value of all.

Echoing the experience of other museum directors around the world, Timothy Rub, the Director of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, recently announced that the Museum will return a ceremonial shield to the Czech Republic following a long look into its provenance and much discussion: “A work that had been lost during the turmoil of World War II is being happily restituted, and out of this has come an exceptional scholarly partnership.”

Finally, among dozens of ongoing discussions about the repatriation of objects, this announcement by Ngaire Blankensberg, Director of The Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of African Art, perhaps best sums up the stakes for both sides: “I can confirm that we have taken down the Benin bronzes we had on display, and we are fully committed to repatriation. We cannot build for the future without making our best efforts at healing the wounds of the past.” There was no condescending talk about “long-term loans” or curatorial evasions like “retain and explain”. These acts are about giving and generosity, which is very different from trading or loaning. Generosity begets gratitude, and this is a powerful combination.

Sometimes, however, the wisest comments come from the unlikeliest sources. In a statement to the New York Times International edition (August 30, 2020), British Museum Director Hartwig Fischer had this to say (inadvertently perhaps) about handling contentious issues involving the Museum’s collections:

“People will always complain; you just have to do the right thing.”

NEXT WEEK: Don Morgan Nielsen explores “The Future of the Museum”, both the book of that title by András Szántó and the challenges and opportunities faced by one of society’s most important institutions – the museum.

ABOUT THE PARTHENON REPORT | DON MORGAN NIELSEN:

In this bicentennial year since the birth of the modern Greek State, of both pandemic and celebration, Greek City Times is proud to introduce readers to a weekly column by Don Morgan Nielsen to discuss developments in the context of history, politics and culture concerning the 200-year-old effort to bring the Parthenon Sculptures back to Athens.

Classicist, Olympian and strategic advisor, Don Morgan Nielsen is currently working with a growing international team to support Greece’s efforts to repatriate and reunify the Parthenon Sculptures.

Featured Image: Copyright Nick Bourdaniotis | Bourdo Photography

Click here to read ALL EDITIONS of The Parthenon Report by Don Morgan Nielsen