That we've broken their statues,

that we've driven them out of their temples,

doesn't mean at all that the gods are dead.- IONIAN, Constantine Cavafy

At the end of the Duveen Gallery in the British Museum, past the pieces of disembodied sculpture hovering above the crowd, you come to a massive wall, like the one now standing between Britain and Greece. Over the past five months, we have engaged in a long and winding conversation about this 'wall'. We have explored its history, viewed it from all possible angles and are now left with the question: where do we go from here? What is to be done with this wall, and if it must come down (it must), what can we build in its place that will be better and more beautiful?

This question leads back 2,500 years to Themistocles surveying the devastation left behind on the Acropolis after the Persians had taken the city and destroyed its temples, as described here by Herodotus (VIII.53):

“Those Persians who had come up first betook themselves to the gates, which they opened, and slew the suppliants; and when they had laid all the Athenians low, they plundered the temple and burnt the whole of the acropolis.”

Themistocles’ first order of business after defeating the Persians was to build a protective wall around the city and to expand and strengthen the ramparts of the Acropolis using parts of the temples destroyed in the previous year’s invasion. In a row near the top of the north wall he placed 24 column drums from the old Parthenon as a monument and reminder, lest anyone forget. And this, more or less, is how we propose the Parthenon Sculptures now be used – to repair and extend Greece’s friendship with Britain, not as a wall but as a bridge to a new and more expansive relationship based on justice and generosity.

In the three decades following the final defeat of the Persian land and naval forces, Athens created something thrillingly new, but still terribly important today: Democracy. For a people who have lived through multiple invasions and occupations, earthquakes, famine and fire, tyrannies, bankruptcies and military dictatorships – the Parthenon has remained a point of reference, a talisman and symbol of the values that the Greek people hold most dear. The Doric column, which reached the peak of its development in the Parthenon, symbolized for them what it means to stand upright and bear a great weight.

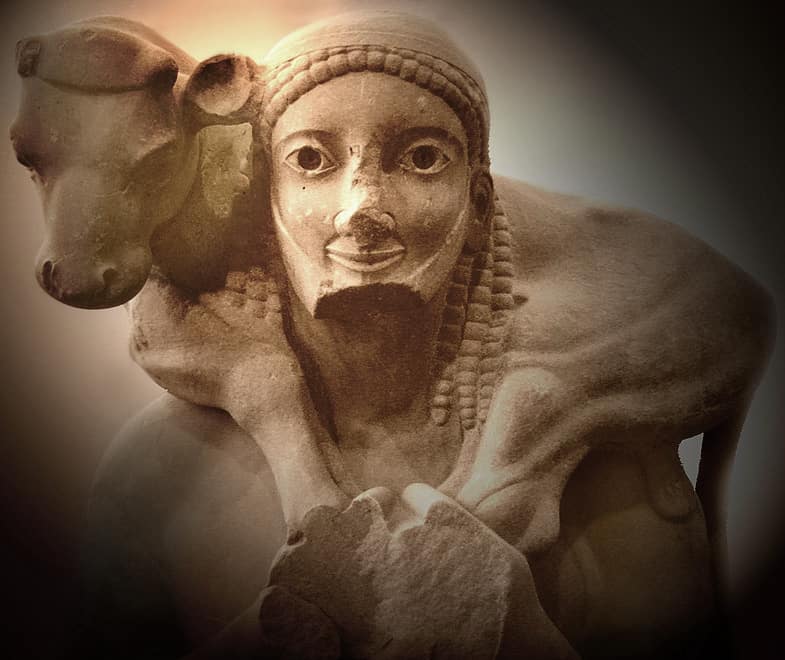

The sculptures of the pediments and metopes depict the founding myths of Athens and the struggle of reason and civilisation against the forces of chaos. Finally, the long procession of the frieze represents the public ritual of democracy, which, as Pericles understood, is fragile and requires constant effort to protect and maintain. This is not just a theoretical concept. People can still recall the sound of tanks rolling down the streets of Athens during the military dictatorship of 1967-74.

Meaning and Possibility

This is the meaning of the Parthenon and its sculptures to the Greek people – and why their return and reunification is so vitally important to them. It is not because the Greeks are paragons of principle and perfection – any more than Americans are the embodiment of their own aspirations of “liberty and justice for all” or that every Englishman is a living example of fair play. What we aspire to, however, is far more important than the frail reality of what we are. As Robert Musil (1880 – 1942) said in “The Man without Qualities”: “If there is a sense of reality, there must also be a sense of possibility.” For the Greek people, the Parthenon Sculptures represent this sense of possibility.

A Gathering Storm

In recent years, there has been a growing consensus that the taking and keeping of other peoples’ cultural heritage – without their consent – is unacceptable, and that arguments to the contrary are merely legalistic excuses and justifications. The Greeks are not alone in calling for the Sculptures’ return. Voices from all quarters are converging on this point, animated by Lord Mansfield’s famous exhortation:

“Let justice be done, though the heavens fall.”

Beyond justice, however, Greece also cares about Britain’s wellbeing and friendship. Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis is a serious man handling crises on several fronts with calm determination. In bringing up the subject of the Parthenon Sculptures with his British counterpart Boris Johnson, Mitsotakis underlined the importance he places on this issue and his intention to use every means at his disposal to reunite the Sculptures in Athens, including legal action if necessary. With historical trends on his side, a strong mandate from the Greek people, and popular opinion in Britain overwhelming in favour of the Sculptures’ return, Mitsotakis is seizing the moment and urging Johnson to do the same.

In one of the most telling signs that the time is indeed right for a just and generous resolution to this dispute, two respected journalists writing for leading British papers have both arrived at this same conclusion from two very different perspectives.

On November 19, Gordon Rayner, Associate Editor at The Daily Telegraph, wrote an article about Mitsotakis’ visit and the prospects for the Sculptures’ return: “Are we about to lose our marbles?”. A day later, Simon Jenkins of The Guardian gave a masterclass on the issue in his article “Give the Parthenon marbles back to Greece – tech advances mean there are no more excuses.”

These and other recent articles absolve me of the need to revisit the details of this case. In 20 columns over the past 5 months, everything has already been said that needs saying about the Parthenon Sculptures and the logic of their return. So, let’s turn to the future for a moment and contemplate a win-win solution under consideration for when the British Government and Museum decide to remove this albatross from around their neck and move forward. When they do, they are unlikely to find more reliable or sympathetic partners for this undertaking than Prime Minister Mitsotakis or Professor Nicholas Stamboulides, the Director of the Acropolis Museum. The world is ready for a solution, and as Shakespeare said (Hamlet, Act 5, Scene 2):

“The readiness is all.”

Radical Generosity: A Win-Win Solution

Quietly, behind all the public statements and interviews, serious preparations have been underway for a number of years to develop a win-win solution that would harness the full force of Greek gratitude and international generosity, a solution which would not cause the heavens to fall but would instead strengthen the British Museum and help it become an international hub for innovation.

Under such a solution, Greece would provide Identical copies of returned antiquities, plus a steady stream of exquisite artefacts on a rotating basis so that the Museum would always have something fresh and fascinating to display. Virtual extensions to the existing galleries, using VR, AR and other emerging technologies, would allow visitors to travel through time and space to explore the ancient world, while scholarships, exchange programs and new archaeological digs would not only spark a renaissance in British-Greek relations but extend to schools and museums in other countries as well. At the heart of these initiatives lies planning for serious international financial support so that the return of the Sculptures becomes a catalyst and first step to something far greater. Patience is still required – and plenty of quiet discussion.

To conclude our long conversation, however, I would like to share a personal story about the power of returning something precious to its original owner – and how the resulting gratitude and generosity can shape lives (and sometimes history). When I was eleven, my faithful but none-too-bright St. Bernard “Manfred”, who appeared briefly as a puppy in the first of these columns, met an untimely end running to meet the school bus.

I was between cats at the time, and the absence of animal companionship made life sad and dull. One night, however, about a month after Manfred’s demise, I heard whimpering outside. Rushing downstairs, I opened the back door to find a muddy beagle, shivering and in obvious distress from several injuries. We rousted the local vet from her bed, and after a long night of beagle-repair, she gave our visitor, whom I had already named “William”, a 50-50 chance of survival. Over the next two weeks, I became William’s full-time nurse and as the injuries began to heal, his physical therapist. Soon, we were friends and partners in all the standard boy-dog activities, such as swimming, fishing and playing in the forest.

Growing up, the bond between a boy and his dog is a sacred thing, and so when my grandfather returned from town one day with a serious expression on his face and said he had some bad news concerning William, my heart sank. At the hardware store he had noticed a flier featuring William’s picture and had called the number listed, talked with the farmer at the other end, and arranged for us to bring William back to his old home the next day. On the long morning drive, William sat on my lap with his head out the window while I hugged him and silently cried. But when we arrived, the joy of their reunion overcame my own pain, and I knew William would be happy.

Almost a year later, a pick-up truck pulled into the yard, and William’s farmer came to the kitchen door carrying a cardboard box with a beagle puppy in it – his thanks for nursing, loving and returning his dog. The next day, when we made our first trip to the vet and then the feed store for dog food, I found that accounts had been set up at both places – a kind of scholarship fund for William Junior. This was my first experience of the healing power of restitution and the force of gratitude it inspires. This is what we will see, on a far grander scale, if the Parthenon Sculptures are returned to Greece.

We conclude The Parthenon Report and look forward to connecting with our readers again next year!

If you have any suggestions, feedback or ideas concerning the whole issue of the Parthenon Sculptures or The Parthenon Report please email: [email protected]

ABOUT THE PARTHENON REPORT | DON MORGAN NIELSEN:

In this bicentennial year since the birth of the modern Greek State, of both pandemic and celebration, Greek City Times is proud to introduce readers to a weekly column by Don Morgan Nielsen to discuss developments in the context of history, politics and culture concerning the 200-year-old effort to bring the Parthenon Sculptures back to Athens.

Classicist, Olympian and strategic advisor, Don Morgan Nielsen is currently working with a growing international team to support Greece’s efforts to repatriate and reunify the Parthenon Sculptures.

Featured Image: Copyright Nick Bourdaniotis | Bourdo Photography

Click here to read ALL EDITIONS of The Parthenon Report by Don Morgan Nielsen