It is world-famous for the Roman ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii, destroyed through the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 C.E., however the newest vacationer appeal in Naples presentations an excessively another aspect of the town.

Opening in June, the Ipogeo dei Cristallini — Hypogeum of Cristallini Sideroad — is a part of a historical cemetery, situated simply outdoor the partitions of Neapolis, as the town used to be referred to as 2,300 years in the past.

Some 2,000 years ago, this lively Naples neighbourhood was a very different place. Situated just outside the walls of Neapolis—the Greek city so respected that even under the Romans, its Hellenistic culture was allowed to flourish—it was once a hilly area composed of volcanic rock.

For centuries, civilizations on the Italian Peninsula have dug into it to sculpt tombs, places of worship and even cave-style dwellings.

The Sanità is no different: Ancient Neapolis’ Greek residents used this area, just outside the city walls, as a necropolis.

Streets now pulsating with life were, back then, river-carved paths between hillocks of tuff. As the Greeks built grand family tombs, those paths became improvised roads in a city of the dead.

Eventually buried by a series of natural disasters, the necropolis’ exact size is unclear. But Luigi La Rocca, head of the Soprintendenza, a government department tasked with overseeing Naples’ archaeological and cultural heritage, says it would have featured “dozens” of tombs.

Multiple bodies were laid to rest in each tomb; whether they belonged to families or members of cultural and political groups remains unknown.

In use from the late fourth century B.C.E. to the early first century C.E., first by the Greeks and then the Romans, the archaeological site is “one of the most important” in Naples, according to La Rocca. Later this year, a small stretch of the long-lost cemetery is set to open to the public for the first time, shedding new light on Naples’ history and ancient Greek artistry.

The four soon-to-be-unveiled graves lie almost 40 feet below Via dei Cristallini, the street that houses the aristocratic di Donato family’s 19th-century palace. Each of the tombs consists of an upper chamber, where Roman funerary urns sit in niches above benches carved for Greek mourners, and a lower burial chamber, where bodies were laid to rest during the Hellenistic period.

Both were filled with statues, perhaps of ancestors, and sculpted eggs and pomegranates—symbols of resurrection. In ancient times, the upper chambers were road level, while the burial spaces were underground.

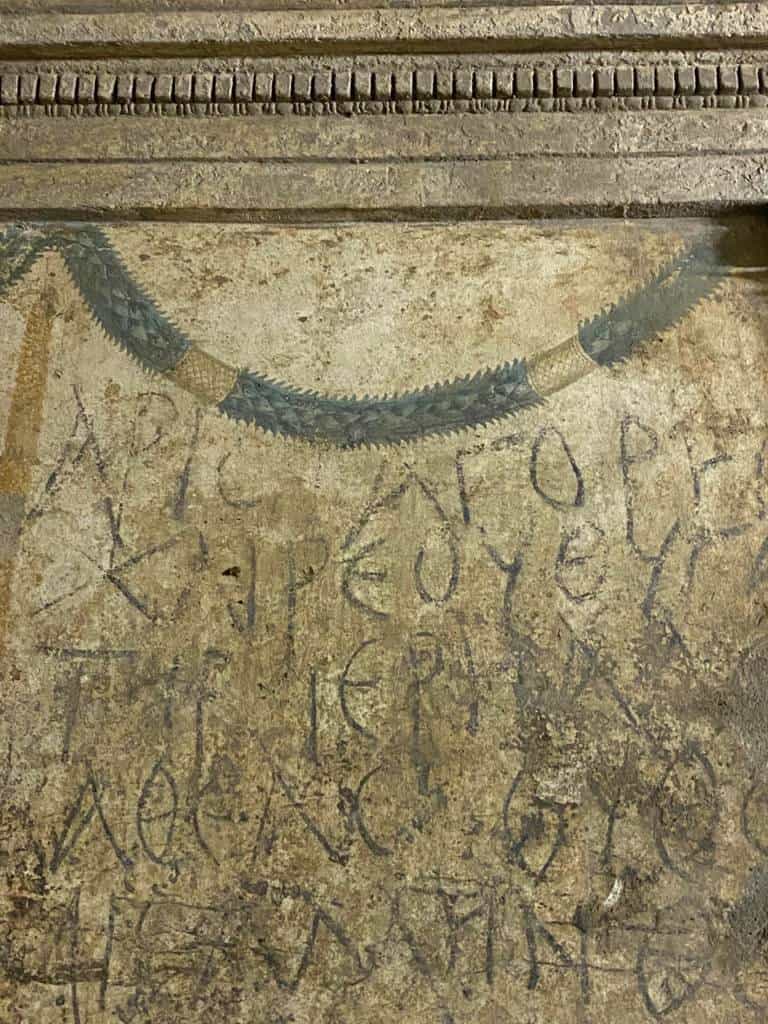

Christened the Ipogeo dei Cristallini, or Hypogeum of Cristallini Street, by modern observers, the tombs’ walls are frescoed with garlands, trompe l’oeil paintings and names scrawled in Greek—a roll call of the dead. In the best-preserved chamber, a gorgon keeps a watchful eye, ready to ward off enemies for all eternity.

“It feels very emotional, descending into the bowels of a city that’s so alive up above, and seeing something as they left it in the first century,” says La Rocca. The site was one of the first he visited after taking up his post in 2019, keen to see if there was any way of opening it up to the public.

“The tombs are almost perfectly conserved, and it’s a direct, living testament to activities in the Greek era,” La Rocca adds. “It was one of the most important and most interesting sites that I thought the Soprintendenza needed to let people know about.” Luckily, the site’s owners were already on the same page.

Workers probably stumbled onto the tombs in the 1700s, when a hole drilled in the garden above destroyed the dividing wall between two chambers. Quickly forgotten, they were officially rediscovered in 1889, when Baron Giovanni di Donato, ancestor of the current owners, dug in the garden in search of a water source for his palazzo.

It’s a unique site, says Federica Giacomini, who travelled from Rome to supervise the ICR’s investigations.

“Ancient Greek painting is almost completely lost—even in Greece, there’s almost nothing left,” Giacomini adds. “Today we have architecture and sculpture as a testimony of Greek art, but we know from sources that painting was equally important. Even though this is decorative, not figurative painting, it’s very refined. So it’s a very unusual context, a rarity, and very precious.”

MANN director Paolo Giulierini agrees. As the caretaker of thousands of objects from Pompeii, he is keenly aware of what he deems an “imbalance” in how Naples and its neighbours are perceived. Though the ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum may lead modern observers to view the area as a typically Roman region, Giulierini argues that Neapolis was “much more important” than those other two towns—a Greek centre of excellence that “stayed Greek until the second century C.E.”

What’s more, he says, the quality of the Cristallini tombs is so exceptional that it confirms Neapolis’ high standing in the Mediterranean region. They are closest to painted tombs found in Alexander the Great’s home territory of Macedonia, meaning they were “directly commissioned, probably from Macedonian maestros, for the Neapolitan elite.”

“The hypogeum teaches us that Naples was a top-ranking cultural city in the [ancient] Mediterranean,” Giulierini adds.