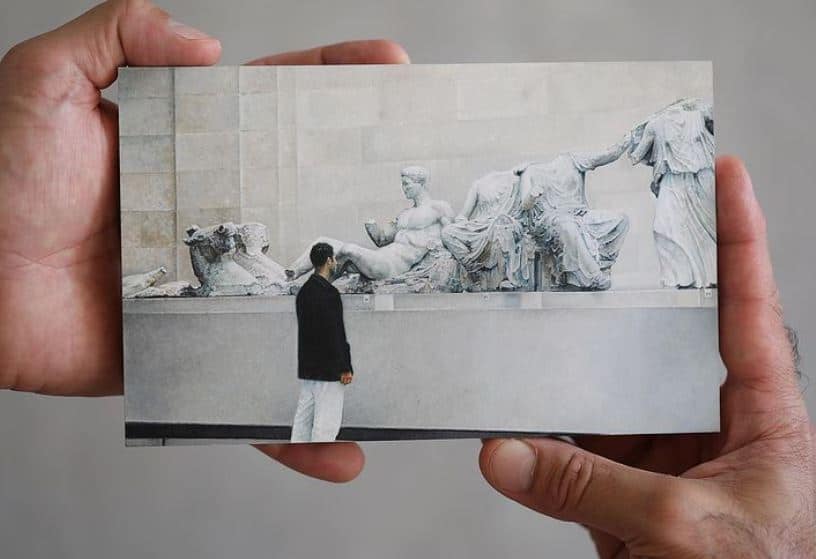

His entry, “At the British Museum”, a miniature self-portrait of the artist crafted in painstakingly photorealistic style, depicts the artist in a contemplative mood standing in front of the sculptures from the Parthenon’s West Pediment in the museum’s Duveen Gallery. You would think that you’re viewing an actual photograph.

Just over 200 years ago a young Romantic poet had stood in the British Museum in London and gazed upon the so-called Elgin Collection of Parthenon Marbles that were controversially and illegally removed from the Parthenon in Athens by Lord Elgin and his men, commencing in 1801.

John Keats stood in differential awe as he contemplated the majesty and sublime beauty of these ancient Greek masterpieces. Keats proceeded to pen a sonnet, On Seeing the Elgin Marbles, marking the occasion of his viewing of the ancient sculptures. His mind was dizzy with swirling ideas and an “indescribable feud” within him as he wrestled with the “dim conceived glories of the brain”. And then in Ode on a Grecian Urn Keats’ sylvan historian is so moved that he can only but enquire: "What men or gods are these?"

Michael Zavros' painting was inspired in part by the artist’s first visit to the British Museum in 2001. According to Zavros:

“People often photograph themselves in front of grand monuments, staking a claim on history and their moment with it. But this tiny painting represents a fleeting, humble and troubled moment before the great marbles of the Parthenon. I was away from home and so were they.”

“People often photograph themselves in front of grand monuments, staking a claim on history and their moment with it. But this tiny painting represents a fleeting, humble and troubled moment before the great marbles of the Parthenon. I was away from home and so were they.”

But the artist also finds inspiration in the activities of others, most notably his “passionate cousin”, Elly Symons, who, as a member of the Australian Parthenon Association, is part of a group of Australian Greeks who are leading the campaign for the reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures.

Zavros also pays tribute to the ABC podcast series by Marc Fennell, Stuff the British Stole, and the episode dealing with the theft of the Parthenon Sculptures, arguably the British Museum’s greatest trophy.

The hyperrealism of Zavros’ work is not simply a reflection of his love of beauty and aesthetics, but a commentary, in the words of one art gallery director, of the artist’s concerns about extremely topical and sometimes really challenging issues around beauty and contemporary society.

In Michael Zavros’ own words:

“Today we live in a world where museums are busily trying to repatriate their ill-gotten trophies to their rightful homes. Meanwhile, in contemporary culture we desperately try to atone for the sins of the past. So how does my provenance, as a second-generation Greek Cypriot boy, whose father’s homeland was stolen by Turkey, inform what I make? This painting is not intended as a political statement, but you cannot avoid seeing it through the lens of current discussions about cultural theft. I feel connected but also at a remove from this moment and from my own history.”

Michael Zavros, like John Keats before him, has used the sculptures' unsurpassed beauty to convey the theme of his artistic work. The stillness and silence of the Parthenon Marbles speak of a past civilisation that may be long dead but is paradoxically still alive in the marbled immortality of the sculptures. Keats sought to engage the truth of the creative Romantic imagination and the reality of human experience when he delivered the immortal words: "Beauty is truth, truth beauty."

Zavros’ delightful photorealist work reproduces that sentiment.

We all look forward to the day when the sculptures are finally returned to Athens and reunited in the Acropolis Museum in their natural and historical context. For, as John Keats famously wrote, a “thing of beauty is a joy forever".

In the meantime, Michael Zavros’ painting will go on display in the Art Gallery of NSW, itself a building heavily influenced by neo-Greek Revival architecture and featuring the names of famous artists and sculptors lettered in bronze below the entablature of the Gallery.

Ironically, one of those prominently featured is Phidias (also spelt Pheidias), the great Athenian sculptor who oversaw the sculptural design and decoration of the Parthenon and the creation of the perfect Phidian forms.

The entry in the Archibald Prize of Michael Zavros’ work, “At the British Museum”, is both timely and perfect.

Phidias and Keats would be impressed.

George Vardas is Co-Vice President, Australian Parthenon Association and

Co-Founder, Acropolis Research Group