The Chairman of the Trustees of the British Museum, George Osborne, has suggested that there is a “deal to be done” with Greece over a sharing arrangement which could see the Parthenon Sculptures divided between London and Athens.

Appearing on the UK new channel LBC (Leading Britain’s Conversation) Osborne, who was appointed to the Chair in late 2021, said:

“I think there is a deal to be done where we can tell both stories, in Athens and in London, if we both approach this without a load of preconditions, without a load of red lines. We sit down as sensible people. We can arrange something that makes the most of the Parthenon marbles. If either side says there is no give at all, then there won’t be a deal.”

But he also added a cautionary rider when he declared that in the British Museum the sculptures “tell a story about civilisation compared to all the other civilisations, China, India, other parts of the Mediterranean; in Greece they only tell the story of Greek civilisation”.

When the interviewer suggested that this could mean you would move some of the sculptures to Greece, at least for a while, and then back to London Osborne replied that such an arrangement may be possible, adding that “sensible people should come up with something where you can see them in their splendour in Athens, and see them among the splendours of other civilisations in London”.

Is this a defining change of direction by the British Museum?

George Osborne has previously set out the museum's position.

The immediate reaction in Athens was predictable. The President of the Acropolis Museum, Professor Dimitris Pandermalis, dismissed the proposal for a sharing agreement between Athens and London, describing it as a “manoeuvre to stop the noise around the sculptures without being a real solution".

David Hill, the Chair of the Australian Parthenon Association and the founding chair of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures, cautiously welcomed Osborne’s gesture and the suggestion that the British Museum Trustees are prepared to talk. According to Hill:

“It is encouraging that the British Museum wants to engage in sensible talks after decades of refusing to even sit down with their Greek counterparts. However, the current idea that has been floated about sharing the sculptures is preposterous and would not solve this important cultural heritage dispute.”

Can there be a deal?

George Osborne was formerly the Chancellor of the Exchequer and First Secretary of State in the UK Government until he left parliament in 2017. When he was appointed to the Board of Trustees of the British Museum, one commentator in the conservative Financial Times sardonically remarked:

“Osborne has even been named chair of the museum, a ceremonial role that mostly involves raising money and refusing to give the Greeks back the Elgin Marbles”.

In February 2022 Osborne was reported to be working on plans to raise funds for a proposed £1 billion long-term renovation and modernisation of the British Museum as part of the so-called “Rosetta Project” which has been devised by the museum’s director Hartwig Fischer. This project envisages galleries focusing less on European history and more on cultural artefacts from Africa and South America as part of a major shift in how the self-proclaimed 'museum of and for the world' projects itself in the future.

George Osborne has also been active in other capacities. In April this year Osborne, as a partner in the boutique investment banker and advisory group Robey Warshaw, was involved in a bid to buy the Chelsea football club from the sanctioned Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich.

But is the resolution of the 'Elgin Marbles' conundrum just another “deal” that sensible parties can reach in spreading the sculptures between Athens and London to different cultural audiences? And does "sharing" mean loans and/or outright transfer of some of the sculptures?

The stark reality is that when George Osborne speaks of pre-conditions and red lines, it is the British Museum that must first move from its long-held position, which is seemingly set in stone, that the sculptures tell a different story in London and any future deal struck must involve a sharing of the marbles.

The issue is much more complicated than a multi-million dollar corporate merger and acquisition, as history teaches us.

British imperial condescension

Twenty years ago, in 2002, the then Greek Culture Minister, Evangelos Venizelos, met with the chair of the British Museum, Sir John Boyd, to discuss the possibility of sharing collections by way of joint curatorial responsibility for the sculptures once they were reunited in the yet to be built New Acropolis Museum in Athens. The response from Bloomsbury was brutal. Venizelos was informed that there is a “prima facie presumption against the lending of key objects in the Museum’s collection” and in this case the Parthenon sculptures were regarded as being among a “group of key objects, indispensable to the Museum’s essential, universal purpose.” Boyd added that he could not envisage the circumstances under which the Trustees would regard it as being in the Museum’s interest, or consistent with its duty, to endorse a loan, permanent or temporary, of the Parthenon sculptures in its collections.

This mindset has been entrenched in Bloomsbury. Ian Jenkins, the former Senior Curator of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum, once wrote that the acquisition of the 'Elgin Marbles' was “arguably the single most important event in the history of the British Museum” and the sculptures themselves were the “most beautiful man-made creations in existence”. But he also contended that at the museum the sculptures had completed a "rite of passage" and had been transformed from architectural ornament to museum art object and now serve to act as a reference point for other cultural artefacts on display at the British Museum.

And so it is that the acquisition of the Elgin collection of Parthenon Sculptures by the British Government - followed by their transfer to the British Museum in 1816 - and the claim that these sculptures are now more a part of the British cultural psyche than when they adorned the Parthenon temple for 2,500 years is the central theme in British Museum-inspired revisionist histories.

This attitude sadly pervades the narrative pushed by the British Museum over the years and continues to resonate in their pronouncements. When George Osborne says that the sculptures tell a story about other civilisations and attempts to downplay the heritage significance of the sculptures in the Acropolis Museum, he is merely echoing statements uttered by his predecessors.

Can the marbles be shared?

The British Museum literally needs to step up.

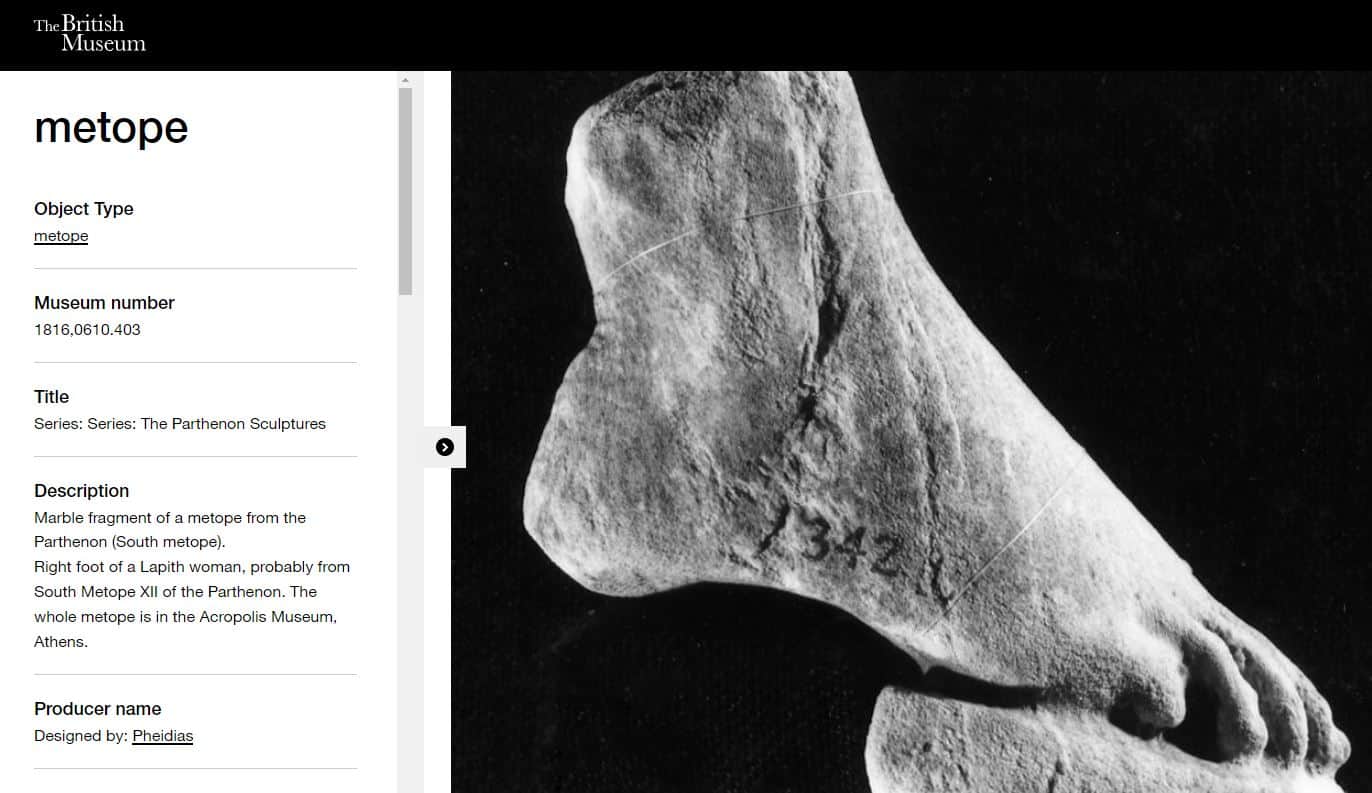

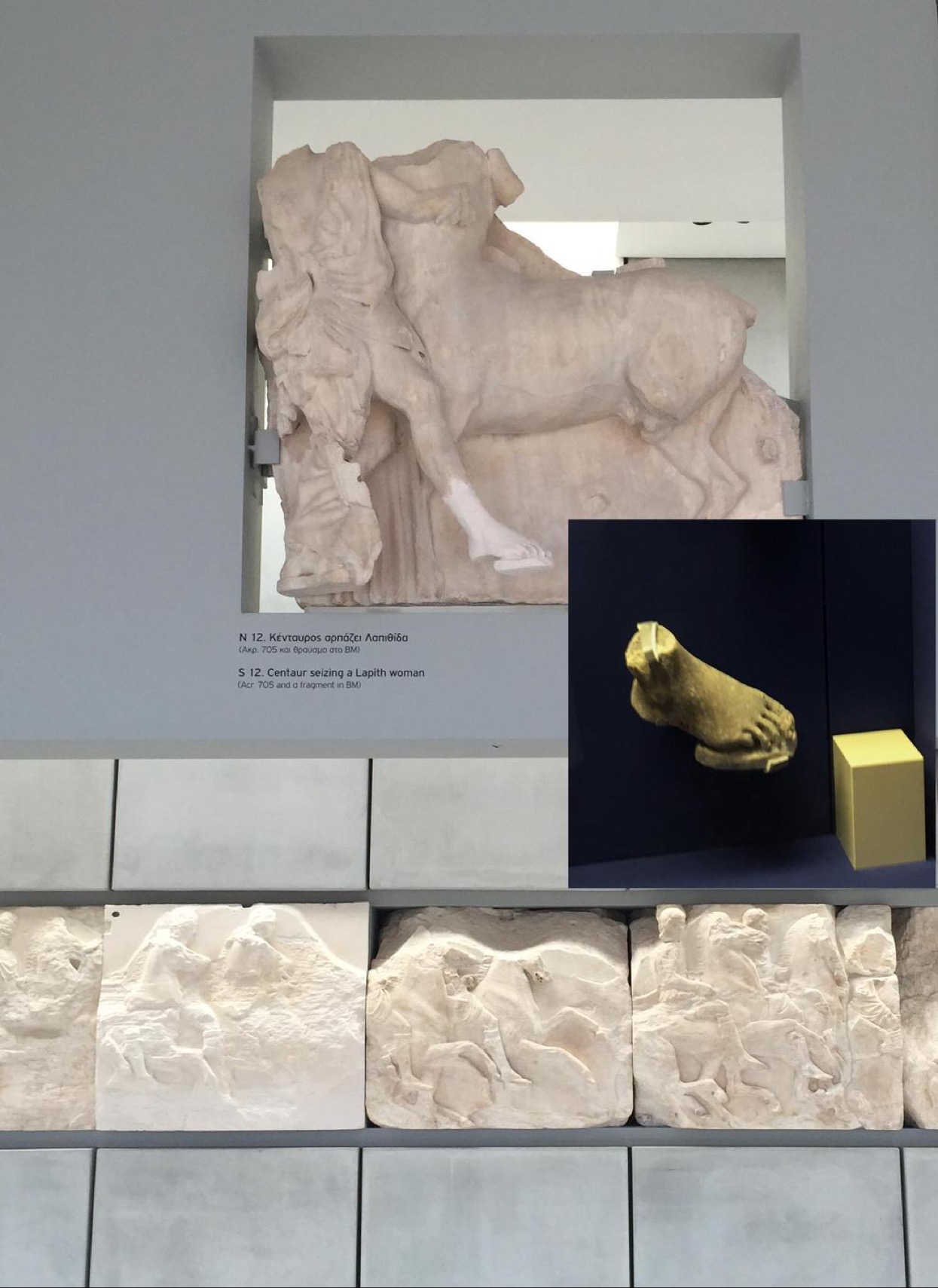

Visitors to the Duveen Gallery in the British Museum must first pass two dimly-lit vestibules on either side to the entrance to the main gallery. There they will find glass wall display cabinets featuring fragments from the Parthenon taken by Elgin’s men. One such fragment is a foot.

In the Guide to the Sculptures of the Parthenon in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities published in 1886 by the British Museum, under the heading “Marble Fragments of Metopes”, this lonely object is identified as the right foot of female figure with the forepart of the sole of her sandal.

As we learn from the guide, the foot belongs to the original metope (no. XII) which adorned the exterior of the Parthenon and which is actually in Athens. The metope depicts a mythical Centaur attempting to abduct a Lapith maiden. The marble sculpture is dramatic. The Centaur grasps the maiden’s left arm with his left hand and while the left foreleg is firmly planted on the ground his right foreleg clasps the left leg of the distraught maiden, pressing at the back of the knee, so as to throw her off balance.

We also learn that it has not been possible to attach the marble foot to its place on the cast of the metope held by the British Museum on account of its weight.

When you visit the magnificent Acropolis Museum in Athens, the surviving metope sculpture is on display in its natural context (together with a cast of the foot to convey the full meaning and sensibility of the sculpture to the viewer). Sadly, the original foot and sandal still languish in a sterile display cabinet in Bloomsbury.

So much for being able to compare the “splendours” of other civilisations in the British Museum.

Another example is the torso of Poseidon from the pedimental sculptures on the Parthenon. The legendary God of the Sea is literally torn between Athens and London (as depicted below on images taken by the author).

What is certain is that it does tell a different story in London - one of imperious detachment and colonial indifference.

The world was recently reminded of this after the UK Ministry of Culture had written to its Greek counterpart in late April, ahead of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee meeting in May 2022, inviting talks to begin at ministerial level only to follow up with avowed denials that any discussions, let alone a meaningful dialogue, would take place. The UK Government’s stated position was that whilst it was happy to discuss cultural co-operation with the Greeks, the Parthenon Sculptures would not be on the agenda of official talks.

And the British Museum from the sidelines was quick to repeat its ancient monologue that the sculptures were legally acquired by Lord Elgin, that they legally belong to the British Museum and the museum is prevented by its own legislation from de-accessioning any parts of its collection.

The Greek Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis (image: ERT)

Only a day earlier, the Greek Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, in a wide-ranging interview given inside the spectacular Acropolis Museum, reiterated the Greek government’s position and urged the British to be bold by offering the Parthenon Sculptures to Greece in order to symbolise the significance and importance of the Athenian Democracy (which gave rise to these Phidian forms) in the wider context and global debate on the need to modernise and strengthen today's democracy in the 21st century.

The last word must go to the renown English columnist, Simon Jenkins, who nails it in the Guardian newspaper:

"One thing is clear. Having half the marbles under the shadow of the Acropolis in Athens and the other half in a frigid Bloomsbury chamber is wrong. It is not sharing a work of art; it is splitting one. This cavalcade of masterpieces should be properly shown together, and that means at the site of their creation, in Athens. Loaned, swapped, sold or whatever, they should go back to Greece. It is understandable that the Greeks have never ceased begging for their return."

I would like to think that sensible and long-overdue discussions can now take place but without the imperious claims by the UK cultural establishment that the Parthenon Sculptures really belong in London and are no longer relevant in Athens.

That is a red line too far.

George Vardas is Co-Vice President, Australian Parthenon Association and Co-Founder, Acropolis Research Group