Does the British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, secretly endorse the return of the Parthenon Sculptures (formerly known as the Elgin Marbles), as recent news coverage suggests?

Both the Greek and UK press have run a story based on some intrepid research by the London correspondent for Ta Nea, Yannis Andritsopoulos, who dug into the archives of the Oxford Union and uncovered several letters written by Johnson when he was the President of the Union in 1986.

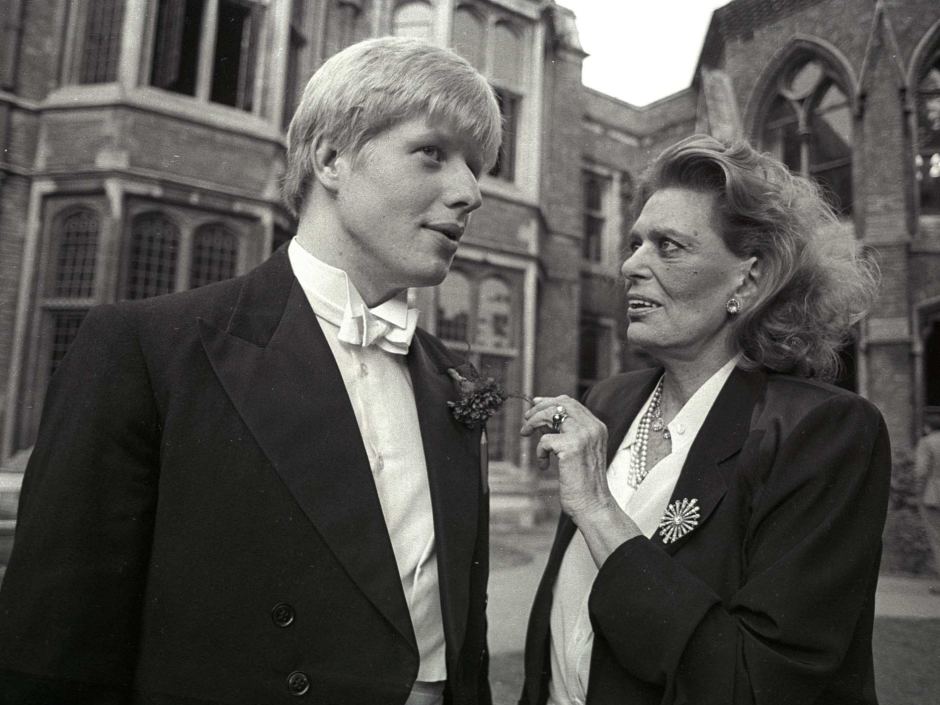

There is a famous photo of a very young Boris listening intently to the Greek Minister of Culture, Melina Mercouri, when she went to Oxford in 1986 to take part in a debate on the return of the Parthenon Sculptures looted by Lord Elgin at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Boris was clearly enamoured by Mercouri and this infatuation gushed over into letters which he wrote to the Greek cultural icon asking her to attend the debate because it would be an “important step” in her campaign for the return of the sculptures and that a successful motion “would send a clear message to the British government that their policy is unacceptable to cultured people”, as though it would have a major bearing on the future of the campaign.

And what was that message? In Johnson’s own words:

“There is absolutely no reason why the Elgin Marbles, superlatively the most important and beautiful treasures left to us by the ancient world, should not be returned immediately from the British Museum to their rightful home in Athens”

The British Prime Minister is known to have a predilection for Classical Greece – with a bust of the famous Athenian statesman Pericles (who ironically oversaw the building of the Parthenon 2,500 years ago) in his office - and the letters written almost 40 years ago are now offered as evidence of a latent Oxonian predisposition for return that now exists in No. 10 Downing Street.

Alas, I am afraid not.

Boris Johnson, even as a 20 year old undergraduate, had grand ideas of his own privileged self-importance and destiny. He went to Oxford University directly from the Eton College - an elite public school - and at his second attempt became president of the Oxford Union. As the Conservative politician Michael Heseltine once remarked, being president of the Union was an opportunity to mix with influential figures and the "first step to being prime minister".

In the book “Chums: How a Tiny Caste of Oxford Tories Took Over the UK” by Simon Kuper we learn that Johnson was part of what the author calls the “Oxocracy” along with other Tories such as Michael Gove, Dominic Cummings and Jacob Rees-Mogg. A more apt description would be ‘upper class toffs’.

As Kuper recounts, at the Oxford Union a speaker might prepare one side of a debate, and then on the day suddenly have to switch to the other side to replace an opponent who had dropped out. It was this rhetorical tradition that prompted the Irish poet Louis MacNeice to comment that having been to Oxford you can never really again believe anything that anyone says.

This may explain why Boris Johnson actually wrote essays for both sides of the Brexit debate when he plied his trade as a journalist at the Telegraph before opting to come down on the side of Brexit in 2016. As Kuper notes, Johnson has spent his whole life seizing the main chance with whatever policies were to hand and “went with the tide while becoming the wave”.

When it comes to the tide of cultural property restitution, Johnson’s views have been laid bare since his student days.

In October 1998 Boris Johnson interviewed Ian Jenkins, then the senior curator of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum, for the Telegraph in the wake of revelations by William St Clair of damage to the sculptures in the Duveen Gallery in the 1930s caused by over-zealous cleaning and scraping. Johnson disparagingly dismissed the mercurial St Clair as an “amateur historian” and readily embraced Jenkins’ description of the marbles as the “pictorial representation of England as a free society and the liberator of other peoples”.

In his paean to Jenkins, Johnson added “anyone who cares about civilization should offer daily prayers of thanks to Lord Elgin who rescued so many treasures from the lime kiln when he went to Athens in 1801”.

In 2004, Johnson, as the MP for Henley, showed his true feelings when he posed this rehearsed question to then UK Culture Minister, Tessa Jowell:

“Does the Minister agree that there is no point whatsoever in sending the Parthenon marbles back to Athens, since there is no prospect of those sculptures ever being viewed in situ on the temple? To do so would be to rip the heart out of the British Museum, which is one of the great cultural landmarks of Europe.”

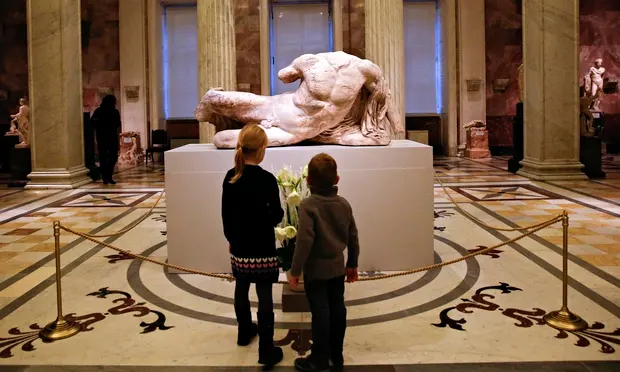

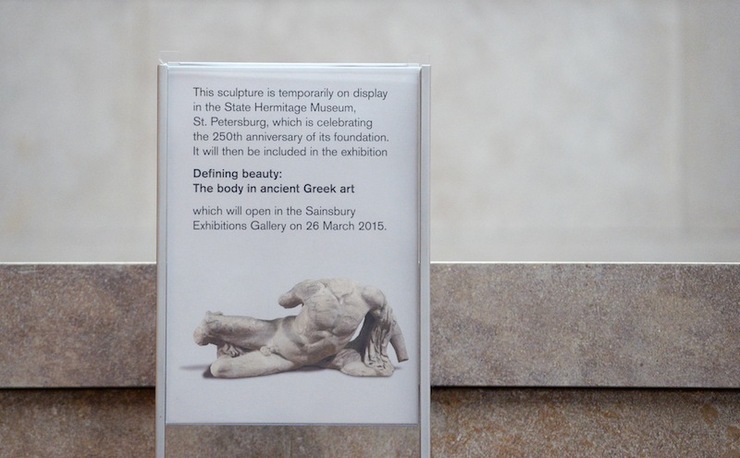

When the British Museum controversially sent the pedimental statute of Ilissos to the Hermitage in Russia in December 2014, Boris Johnson, who was now the Mayor of London, was critical of the timing (after Putin had made his first barbaric inroads into the Ukraine) but still lauded the British Museum because of its independence from government. Describing the Duveen Galleries as the “holy of holies, the innermost shrine of that cultural temple” Johnson wrote that the British Museum’s was free to loan Ilissos to Russia and concluded “that shows exactly why the Elgin Marbles belong and shall remain in London”.

As Prime Minister, nothing has changed. In late 2021 Johnson informed his Greek counterpart, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, in steadfast Bloomsbury-speak, that the British Museum operates independently of the government and that the UK government maintains that the sculptures were legally acquired by Lord Elgin under the appropriate laws of the time and have been legally owned by the British Museum's trustees ever since.

Boris Johnson simply cannot be trusted. A third of his own Conservative Party parliamentary colleagues recently supported a no confidence motion to remove him. His position on important issues fluctuates like the tide and Britons are starting to realise that the chief spruiker of Brexit may be leading them into a financial abyss.

And when it comes to the Parthenon Sculptures, it is apparent that the real Boris Johnson still stands with the British Tory establishment and is not about to lose his marbles.

George Vardas is Co-Vice President, Australian Parthenon Association and Co-Founder, Acropolis Research Group