A brisk walk from Omonia in the heart of Athens takes you to Stadiou Street. Once upon a time, you'd encounter high end boutiques and fancy cafes on this strip that leads to Syntagma, where the imposing Parliament shadows the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

A profile of Christos Ikonomou

Nowadays, you'll find two-bit euro shops, shuttered kiosks and broken glass at your feet. Outside the blasted slabs of the once-elegant Attikon cinema, you can run your fingers across the crenulated metal barrier that's been spray painted with defiance: 'Freedom is Won with Weapons'. This snapshot of Greece, equal parts democracy to destruction- serves as a backdrop to artists of every kind: anti-fascist rappers, graffiti muralists, and writers.

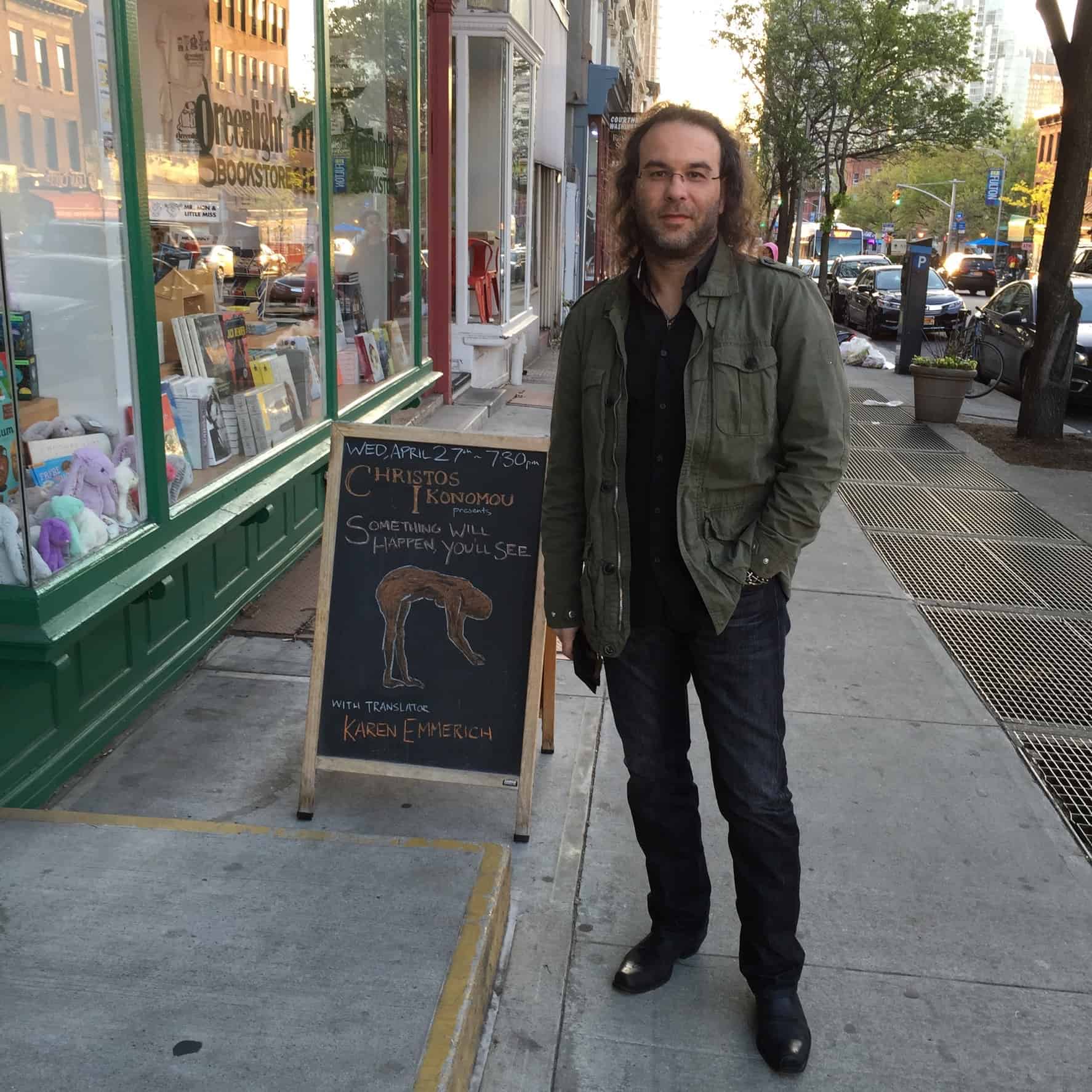

Here I met Christos Ikonomou on a scorching day in July. Over a cool frappe inside the Ianos bookstore on Stadiou I interviewed this rising star of Greek literature. Accolades have been heaped upon his short stories for good reason, they are acutely drawn portraits- lives of quiet desperation of Greeks that resonate with intensity, emotion and truth.

At Ianos Ikonomou gives creative writing classes to aspiring authors, when not bolted to his desk on the outskirts of the city (Ianos thankfully survives, yet the terminal decline of the Eleftheroudakis chain of bookshops, active since 1868 a citadel of culture has been catastrophic). Ikonomou related his upbringing and being shifted around the country according to his father's placement in the Greek army. As a military man his father was transferred to Souda Bay where the American base continues as an arm of US influence in the Mediterranean.

In fact, the authoritarian regime of the junta (and its ties to the CIA) is long gone, but its repercussions remain strong amongst everyday Greeks: the distrust of the state remains, be it the government, the police or the judiciary. Add to that a crippled education system, the corruption of politics beginning at university level (Ikonomou called them skilo-kommota) and there's little hope left for a better civil society. Greece exited that particular nightmare of the 20th century, only to emerge into another oppressed time, decades later. Grist for the mill for writers to document reality beyond the headlines.

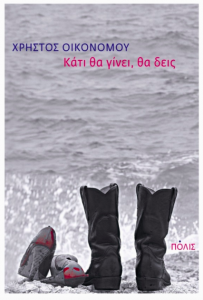

Something Will Happen, You’ll See consists of sixteen intricately woven tales that make up a tapestry of Greece during a fraught period of history. Seven years in the making and published in Greece in 2010 to wide acclaim (translated into English without losing any of its surface grit), these short stories have been described by critics as 'a bucket of cold water to the face'.

Don't expect redemptive tales set on Aegean islands be it of the Shirley Valentine type nor bombastic Zorbas philosophising on the beach (although Ikonomou hugely respects Nikos Kazantzakis). Inspired by Thus Spake Zarathustra and the fabulist tales of Jules Verne, Ikonomou journeys to the interior worlds of the battered psyches of Greeks under the pump. Existential struggles at the most vicarious level are illustrated with minimal fuss. Modest victories are borne from excruciating realities. Of course the writing was on the wall for Greece before 2010 when the bailouts/austerity/economic recession blew away the hazoharoumeni 'happy- silly' culture that prevailed during the Athens Olympics in 2004.

In Ikonomou's portraits of ravaged lives, you'll find ex-workers 'as disposable as cigarette butts', parents on a shoe-string budget trying to satisfy the growls of hunger from their kids, and the suppressed violence of the aging in queues to clinics that have had their resources decimated. There's no need to spell it out, the crisis is not stated, it's evoked by the fear of the phone ringing from creditors, the angst over an envelope lying on the kitchen table that carries the threat of electricity disconnection and the anxiety in measuring one’s life in 15 day chunks awaiting a wage payment that may never arrive.

Ikonomou's stories are set in the Perama zone, a part of Attica that “spreads out in front of you like a dirty, wrinkled blanket” and so removed from the tourist view of Athens says Ikonomou, that even Athenians regard this territory as 'exotic'. Halyvourgeia Steelworks, Skaramangas Shipbuilding and the Hellenic Oil Refineries are situated in the congested precinct west of the Acropolis that pollutes even ancient icons; Elefsina lost its appeal when chimneys and smelters encircled its mysterious ruins.

Suburbs like Aspropyrgos have since become wild west outposts thanks to de-industrialisation. Streetlights here emit a sickly yellow beam, creating melancholy or threat should you happen to accidently drive through (Golden Dawn gloomily advertises a branch office in Aspropyrgos, and this neo Nazi organisation has made significant inroads in tapping working class resentment, a conversion from the Communist Party that Ikonomou derides as pathetic). Ikonomou writes 'it rains hatred over Amfiali' suggesting suburbs like Perama and Nikaia and Amfiali are places prone to random violence. In 'Placard and Broomstick', we see the futile protest for a co-worker’s electrocution in these very suburbs, and the co-workers who stab each other in the back to preserve their job. The vernacular Ikonomou uses is the poetry of the grim suburbs: malakas, putanes, pousti stand beside people 'who are streinz'.

And yet curiously, Something Will Happen, You’ll See is a love letter to the port of Piraeus. The yellow bollards, piers lashed by waves, taut ropes, the smell of diesel refuelling bulky carriers, and the rumble of semi-trailers as they enter the hull is writing at its most concrete. The port remains a site of enchantment rather than the marble fort high up on the Acropolis. The port is where "the sea meets the land, where everything is both together and apart, where people come together or part”. From the perspective of the grim suburbs, aspirations are horizontal, not vertical. The port, with its promise of transcendence over the blue horizon, is a poke in the eye to the city's fort and temple, that mesmerises foreigners and nationalists alike.

At the Acropolis, the hierarchy of gods to mere mortals stands tall. But the gods in Ikonomou's narratives have fled. Each individual must bear the weight of his past or roll his traumas uphill. Don't expect salvation here, only the savouring of tiny victories like a chocolate Easter egg for the young and a cigarette passed between strangers for the old. We must imagine Sisyphus happy on a futile quest wrote Camus in the 1940s. Ikonomou you'd suspect would continue to agree.

Along with an anthology of new Greek Poetry Austerity Measures (published by Penguin this year), Greece's fraught era is addressed in various tones and registers by writers of all kinds under 50, suggesting that the literary is undergoing a renaissance. Regrettably, Ikonomou believes emerging writers don't have faith in themselves or regard the act of authorship as crucial to the health of society. For me, the economic crisis has created a crucible that has concentrated minds on the essentials. I felt an underlying resilience amongst Greeks doing it tough. I often heard whispers, "something good will come about the crisis; you'll see."

*Christos Ikonomou; Something Will Happen, You'll See (trans. Karen Emmerich)