The way one writes about their history reflects the way they perceive their place and role in time and space. In this respect, historiography is historical consciousness. And if there is a hierophanic life-order – or what we usually call religion – which is rooted in historical consciousness, that certainly is Christianity. Orthodoxy, in particular, is treated many a time as that member of the Christian family with the least developed sense of its own historicity, but such an understanding is rather superficial and biased.

The way one writes about their history reflects the way they perceive their place and role in time and space. In this respect, historiography is historical consciousness. And if there is a hierophanic life-order – or what we usually call religion – which is rooted in historical consciousness, that certainly is Christianity. Orthodoxy, in particular, is treated many a time as that member of the Christian family with the least developed sense of its own historicity, but such an understanding is rather superficial and biased.

In reality, the Orthodox Church has its own sense of history, a sense which in the case of modern times – let’s say the 20th century – speaks volumes as to how dominant ecclesiastical groups or interests have shaped the perceptions of the faithful and framed the understanding of events that are supposedly the most important.

I would like to draw attention to events, movements and trends that have been overlooked or at least not appreciated as much as they deserve, leading thus to a somehow distorted representation of modern global Orthodoxy. Thus, I am not interested in what one can find in books on modern Orthodox history (mainly with regards to prelates and the interface between the Church and the State), but in what one cannot or would not normally find there.

Modern Martyrdom

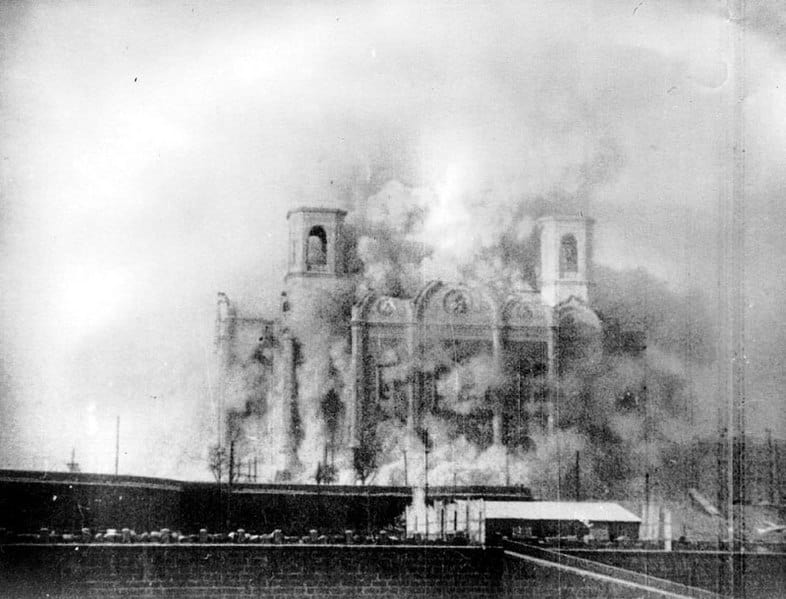

There are hardly any modern ecclesiastical histories in which persecutions against the faithful on the part of communist regimes feature prominently or even adequately. I can confidently say that one would be disappointed if they were to trace the interest of the ecclesiastical historian on this specific subject.

To be sure, the martyrs of the 20th century are mentioned here and there in some other theological genres (mostly pastoral or hagiographical), but they do not constitute a proper subject for the Church historian. I wonder why. Isn’t ‘the blood of the martyrs [always] the seed of the Church’, to recall the famous phrase of Tertullian? I suppose so, but this does not seem to have been enough for the Church historians that study the 20th century.

Nevertheless, the persecutions of the Orthodox faithful under the communist regimes should hold a place in our historical consciousness similar, if not greater, than the one the ancient martyrs hold in the historical memory of the liturgical tradition and the theological consciousness of the Church. And to be quite blunt, political tactfulness, expediency or correctness should not blind us as to the triumphant moments of the Church or undermine the cherished memory of countless brothers and sisters in Christ.

Modern Theology

A movement directly related to the communist persecution of the Orthodox faith was the flourishing of theology and religious thinking within the Russian diaspora. In the early 20th century, a substantial number of theologians and/or philosophers went into self-exile in Western Europe, especially France. St Sergius Institute in Paris will become an emblematic centre for the cultivation and promotion of Orthodox theology vis-a-vis the developments in Western thinking, art and science.

The intellectual figures involved (S. Bulgakov, J. Meyendorff, G. Florovsky, A. Schmemann, P. Evdokimov, to name a few) in this institution, but also the figures of the broader Russian diasporic community (such as V. Lossky, N. Berdyaev and M. Skobtsova) were instrumental in forming the most potent, influential and creative Orthodox theological movement of the 20th century – with a wide range of influences until nowadays. It would not be an exaggeration to say that it is thanks to the Russian émigré theologians that the whole of modern Orthodox theology has been accustomed to a specifically modern way of thinking.

However, this tremendous intellectual enterprise hardly features in histories of modern Orthodoxy; one might come across some minor or major references to it in broader works on the history of European ideas, but there is hardly an appraisal of its contributions to the life, the course and the historical profile of modern Orthodoxy. As if there could ever be an Orthodoxy without a concomitant theological consciousness!

Modern Sainthood

If the Slavic Orthodox world has had its martyrs, the Greek Orthodox world has had its genocide. The Young Turks regime will attempt systematically to exterminate all indigenous Orthodox presence in Asia Minor and Pontus, leading thus to the biggest catastrophe in the history of Hellenism and the most deplorable destruction of age-long ecclesiastical life. Not only ancient Christian centres will be literally wiped off the map, but perhaps more tellingly the Ecumenical Patriarchate will lose most of its flock in just a few years.

Apart from the horrible consequences of this development per se, it will open the way for two major phenomena in 20th century Orthodoxy. The first is the activation of the Ecumenical Patriarchate’s jurisdictional responsibility over new global territories – a theme which for obvious reasons does take up a good number of pages in modern ecclesiastical histories – whereas the second is the transplantation, so to speak, of Orthodox piety from one to the other side of the Aegean Sea in the form of some of the most original examples of modern sainthood (St Georgios of Drama, St Paisios the Athonite, St Iakovos of Evia, St Sofia of Kleisoura).

Imagine, now, if only modern ecclesiastical histories were written in light of where the Church is really manifest, that is, in the lives of saints such as the aforementioned ones and not in the worldly dealings of Church authorities! But I suppose this is a history we won’t be reading for some time to come...

Modern Disputes

Another milestone in modern Orthodoxy that is totally missing from the relevant historical literature is the schism of the Old Calendarists or Old Feasters. Since 1924, when the Church of Greece (and other local Churches) adopted the revised Julian calendar for liturgical life, many faithful resisted and formed what they believed (and still believe) to be the True Orthodox Church. Especially in Greece this development has been a total mess both in itself – creating splinter groups upon splinter groups and radical fundamentalist responses in practice and theory – but also in its relation to the broader society and Church, for the State reacted with measures of severe persecution, discrimination and other means of exclusion.

The main issue is that this schism was created virtually out of nothing, and instead of being healed through a spirit of brotherly care and love it was further consolidated through official – both on the part of State and Church – policies. A hundred years afterwards, the problem still exists, there is no interest in solving it, and there is a suspicious – if anything – silence as to its historical character and dynamics. In other words, another aspect of modern Orthodoxy that receives no mention whatsoever, although it has affected so negatively the lives of millions of faithful throughout the last century!

Mission: Creating the Future of Orthodoxy

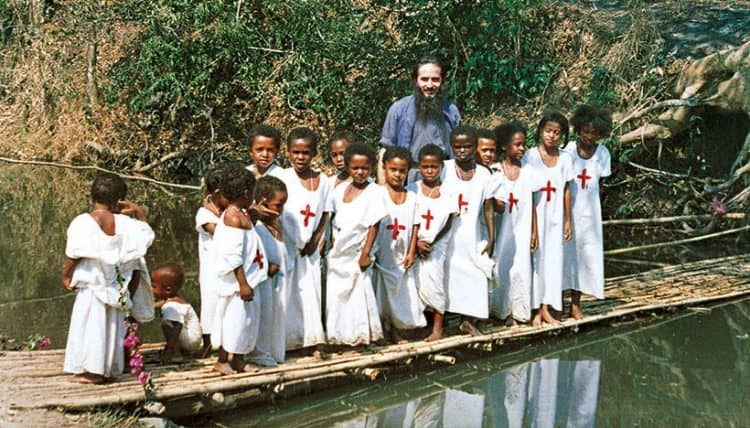

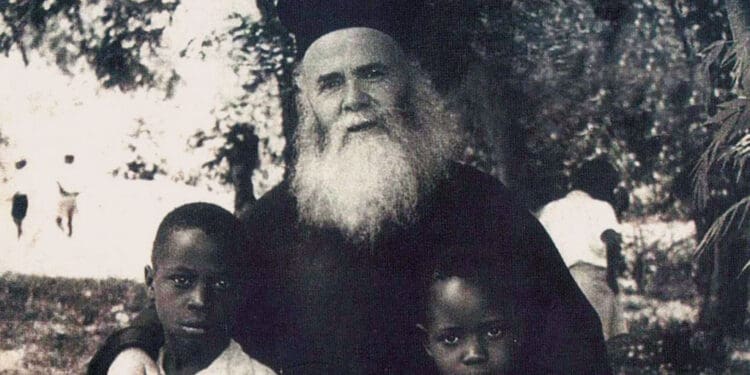

Last but not least, I would like to mention Orthodox missionary activity in the 20th century. This is an amazing (hi)story that no one has ever told or written as an integral part of the history of the modern Orthodox Church. Again, we find references here and there, but not a truly historical and at the same time ecclesial appreciation of its impetus and pathfinding qualities. How many of us know that there are millions of Orthodox Christians in Africa right now? How many of us realise that the hour of Orthodoxy in Asia is close at hand? It has been through the sacrifices of men and women, nuns and priests, laypeople and clerics, that Orthodoxy has spread miraculously throughout non-traditionally Orthodox lands, creating the future centre for Orthodoxy in the Global South.

In any case, the examples I have chosen to discuss are meant only as an occasion for reflection; an occasion for our imagination to envision what it would mean if we were to rewrite our Orthodox history from the perspective of modern martyrdom, progressive theology, the trauma of genocide, the burden of schism and the hope of totally new local Churches. But before that, we need to ask and answer the tough questions.

Why did God allow faith to be so severely persecuted in traditionally Orthodox countries? Why did God allow the destruction of so many centuries of Church life? Does God want us to come up with a new paradigm of theology? What kind of sainthood can overcome the ‘terror of history’? Are we to boast about Christian unity when we haven’t established it amongst us in the first place? Does the future of Orthodoxy lie far away from its past, ‘where the streets have no name’ yet?

ABOUT | INSIGHTS INTO GLOBAL ORTHODOXY with Dr Vassilis Adrahtas

"Insights into Global Orthodoxy" is a weekly column that features opinion articles that on the one hand capture the pulse of global Orthodoxy from the perspective of local sensitivities, needs and/or limitations, and on the other hand delve into the local pragmatics and significance of Orthodoxy in light of global trends and prerogatives.

Dr Vassilis Adrahtas holds a PhD in Studies in Religion (USyd) and a PhD in the Sociology of Religion (Panteion). He has taught at several universities in Australia and overseas. Since 2015 he has been teaching ancient Greek Religion and Myth at the University of New South Wales and Islamic Studies at Western Sydney University. He has published ten books. He has extensive experience in the print media as editor-in-chief, and columnist, and for a while he worked as a radio producer. He lives in Sydney, Australia, his birthplace.