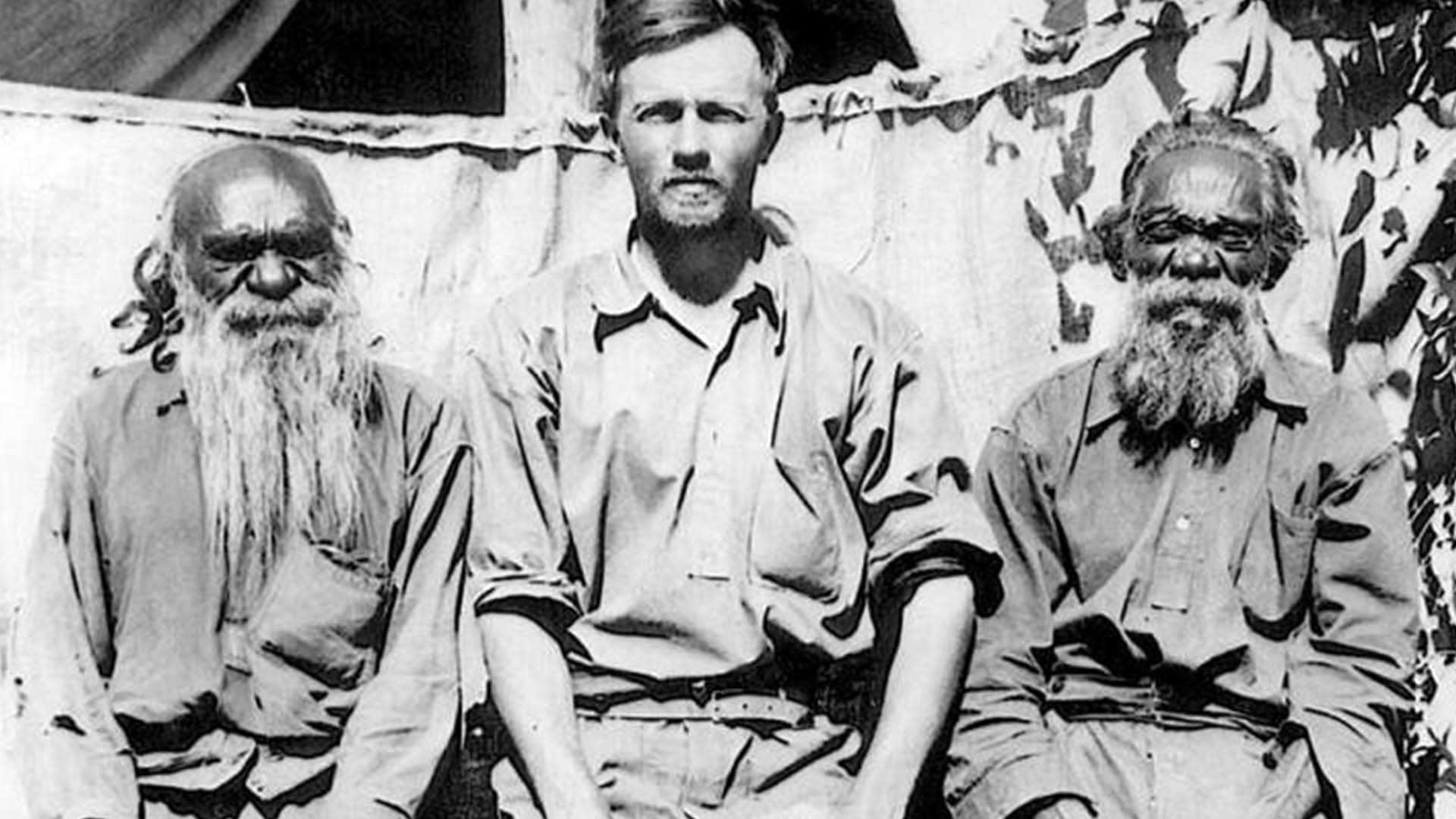

Amateur ethnographer Francis Gillen, along with anthropologist Baldwin Spencer, were the first to mention the term alcheringa as back as the last decade of the 19th century, in order to denote what the Arrernte and other Indigenous Australian peoples of the Central Desert regarded as their far distant past or the ‘dream times’. There are lots of misconceptions involved therein, but it seems that the term does signify what I would dub an immemorial backdrop to the realisation of Indigenous life-worlds. The whole semantics of the term become even more complicated if one considers the range of diverse meanings that it acquired post/colonially – from eternal to uncreated to God himself.

To be sure, altjirrinja (which is a better rendition of the Arrernte word) has been pivotal in the conceptualisation of the Dreaming and, by extension, the latter’s impact on Australian popular culture. In this respect, temporality and dream-like qualities are probably here to stay with the term: it instinctively evokes the notion of a primordial time – something very close to the expression in illo tempore (‘in that time’), as Romanian historian of religion Mircea Eliade would say – and it also comes with strong connotations of an altered consciousness experience, something like a special dream-state. Do we need to get rid of these assumptions? Not necessarily, but they shouldn’t monopolise or, even more, they shouldn't be the focus of our understanding.

To be sure, the Dreaming is what Indigenous Australians would recognise as their Sacred; a Sacred that is seen as present in the here-and-now through its diverse and multiple dreamings. But insofar as altjirrinja is concerned, this Sacred and its concomitant manifestations are experienced primarily as eternal, uncreated and self-originating – yet, at the same time, as happening, appearing and becoming. For the outsider this might look like a paradox, but for the insider it is not; it is but the natural duality of life. In other words, altjirrinja is the word the Arrernte would use when faced with the invisible constant of the visible fluidity of all things around them.

Seeing Things Otherwise

The dreaming connotations of altjirrinja show, if anything, that the term is about seeing and beholding – something special, for that matter, and in an exceptional way. If by ‘dreaming’ one intends to refer to a way of witnessing certain things, people, events or actions, that relates to who someone is and holds great importance for them, then the term does serve its purpose. But the crucial point is: What sort of way are we talking about? What way is this that renders everything it encompasses so paradigmatic? Anthropologist W. E. H. Stanner is the one who has offered the most insightful answer in this connection. According to him – to put it as straightforward as possible – anything constitutes altjirrinja as long as they present themselves as everywhen, that is, when their any-and-each-time realisation is their every-and-all-time existence.

This sounds quite like what we could call ‘eternity’ in a Western cultural context (in the broad sense of the term). This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it might be misleading, especially if ‘eternity’ is taken to presuppose some kind of temporality, for in the Arrernte case – and more generally the Indigenous one – the truth is the other way around, that is, their sense of temporality presupposes their experience of the ‘eternal’ altjirrinja. Thus, in the context of the Arrernte life-world whatever happens – in everyday life, in ceremony and, even more importantly, in ritual – is supposed to reveal the pattern or structure that provides everything with their distinctive and irreducible form. In this respect, altjirrinja is the eidos, that is, the abiding form of something, that irrupts into one’s field of perception and consciousness. And as such it truly constitutes an E-vent – the coming out of its source, of its own self!

Pointing towards an Eschatological Envisioning

Seeing things otherwise is something implied by the Arrernte phrase altjire rama, namely, ‘to behold the eternal’, which makes one automatically think of the place and importance that the vision of God has in the Christian tradition – and, for that matter, the Orthodox Christian tradition. Thanks to the Orthodox hesychast movement (an ascetic-theological movement of the 14th century that put forward as a criterion of Orthodoxy the teaching that God is literally visible in the form of His uncreated energies) the experience of Divine visuality through transformed human vision is something that could be explored creatively in relation to the Indigenous experiencing of heightened hierophanic vision. Although the former is about God and the latter is about this or that aspect of reality, they could be thought of as sides of the same coin: hesychasm emphasises the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of transformation, whereas Arrernte hierophanics stresses the state of transformation per se.

Altjirrinja ngambakala is another expression that translates into ‘what comes out of its own eternity’, which based on what I have already reflected upon could equally be rendered as ‘what comes out of its own abidingness’. But where is this abidingness? Where should we locate it? In the past, the present or the future? For Indigenous peoples these questions are redundant, for the abidingness of things happens any time, each time, every time and all time; in other terms, time is not really an issue… On the other hand, though, when the Christian Eschaton is considered, namely, the all-encompassing and all-pervading presence of Jesus Christ, which is experienced as an Event-from-the-Future, one wonders if the temporal register of the whole thing is really a problem for an Orthodox – Arrernte hierophanic dialogue. I firmly believe that it is not, for in terms of eschatology the future Eschaton-Christ is always associated with the here-and-now of the faithful – it constitutes an ever-present!

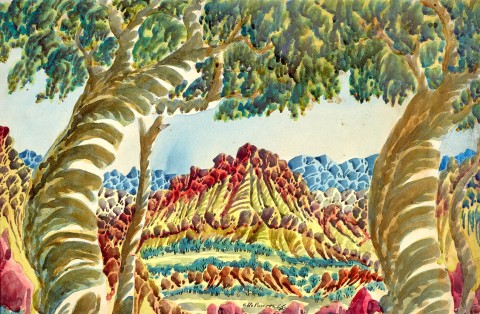

The Indigenous every-when and the Orthodox ever-present can indeed meet and fuse into an integral whole. This would most likely lead to the envisioning of an Indigenous Kingdom of Heaven. The focus in such a hierophanic experience would not be on God or the future; nor would it be on the specificity of place or its paradigmatic nature. Rather, it would be on the transformed vision of nature’s abiding condition in the person of Jesus Christ. In this case, Jesus Christ would be seen as the altjirrinja par excellence, out of which the cosmos and humanity would emerge in their abidingness as the Kingdom of God, perceived and enjoyed by everyone’s dreaming-like vision.

It seems, thus, that the ongoing tension and opposition between Indigenous Topos and Christian Utopia can be resolved and transcended on the basis and in light of an Orthodox understanding of eschatology, that is, one that privileges the internalisation of the meta-historical promise of Utopia so that its actualisation may come true within the Topos of history.

ABOUT | INSIGHTS INTO GLOBAL ORTHODOXY with Dr Vassilis Adrahtas

"Insights into Global Orthodoxy" is a weekly column that features opinion articles that on the one hand capture the pulse of global Orthodoxy from the perspective of local sensitivities, needs and/or limitations, and on the other hand delve into the local pragmatics and significance of Orthodoxy in light of global trends and prerogatives.

Dr Vassilis Adrahtas holds a PhD in Studies in Religion (USyd) and a PhD in the Sociology of Religion (Panteion). He has taught at several universities in Australia and overseas. Since 2015 he has been teaching ancient Greek Religion and Myth at the University of New South Wales and Islamic Studies at Western Sydney University. He has published ten books. He has extensive experience in the print media as editor-in-chief, and columnist, and for a while he worked as a radio producer. He lives in Sydney, Australia, his birthplace.