The magnificent temple on the Acropolis of Athens, known as the Parthenon, was built between 447 and 432 BC in the Age of Pericles, and it was dedicated to the city’s patron deity Athena.

The temple was constructed to house the new cult statue of the goddess by Pheidias and to proclaim to the world the success of Athens as leader of the coalition of Greek forces which had defeated the invading Persian armies of Darius and Xerxes. The temple would remain in use for more than a thousand years, and despite the ravages of time, explosions, looting, and pollution damage, it still dominates the modern city of Athens, a magnificent testimony to the glory and renown the city enjoyed throughout antiquity.

The project to build a new temple to replace the damaged buildings of the Acropolis following the Persian attack on the city in 480 BC and restart the aborted temple project begun in 490 BC was instigated by Pericles and funded by the surplus from the war treasury of the Delian League, a political alliance of Greek city-states that had formed together to repel the threat of Persian invasion. Over time the confederation transformed into the Athenian Empire, and Pericles and therefore had no qualms in using the League’s funds to embark on a massive building project to glorify Athens.

The Acropolis itself measures some 300 by 150 metres and is 70 metres high at its maximum. The temple, which would sit on the highest part of the Acropolis, was designed by the architects Iktinos and Kallikratis, and the project was overseen by the sculptor Pheidias. Pentelic marble from the nearby Mt. Pentelicus was used for the building, and never before had so much marble (22,000 tons) been used in a Greek temple. Pentelic marble was known for its pure white appearance and fine grain. It also contains traces of iron which over time has oxidised, giving the marble a soft honey colour, a quality particularly evident at sunrise and sunset.

The name Parthenon derives from one of Athena’s many epithets: Athena Parthenos, meaning Virgin. Parthenon means ‘house of Parthenos’ which was the name given in the 5th century BC to the chamber inside the temple which housed the cult statue. The temple itself was known as the mega neos or ‘large temple’ or alternatively as Hekatompedos neos, which referred to the length of the inner cella: 100 ancient feet. From the 4th century BC the whole building acquired the name Parthenon.

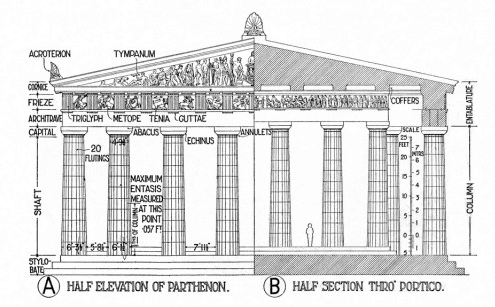

PARTHENON DESIGN & DIMENSIONS →

NO PREVIOUS GREEK TEMPLE WAS SO RICHLY DECORATED WITH SCULPTURE

The Parthenon would become the largest Doric Greek temple, although it was innovative in that it mixed the two architectural styles of Doric and the newer Ionic. The temple measured 30.88 m by 69.5 m and was constructed using a 4:9 ratio in several aspects. The diameter of the columns in relation to the space between columns, the height of the building in relation to its width, and the width of the inner cella in relation to its length are all 4:9. Other sophisticated architectural techniques were used to combat the problem that anything on that scale of size when perfectly straight seems from a distance to be curved. To give the illusion of true straight lines, the columns lean ever so slightly inwards, a feature which also gives a lifting effect to the building making it appear lighter than its construction material would suggest. Also, the stylobate or floor of the temple is not exactly flat but rises slightly in the centre. The columns also have entasis, that is, a slight fattening in their middle, and the four corner columns are imperceptibly fatter than the other columns. The combination of these refinements makes the temple seem perfectly straight, symmetrically in harmony, and gives the entire building a certain vibrancy.

The outer columns of the temple were Doric with eight seen from the front and back and 17 seen from the sides. This was in contrast to the normal 6x13 Doric arrangement, and they were also slimmer and closer together than usual. Within, the inner cella (or opisthodomos) was fronted by six columns at the back and front. It was entered through large wooden doors embellished with decorations in bronze, ivory, and gold. The cella consisted of two separated rooms. The smaller room contained four Ionic columns to support the roof section and was used as the city’s treasury. The larger room housed the cult statue and was surrounded by a Doric colonnade on three sides. The roof was constructed using cedar wood beams and marble tiles and would have been decorated with acroteria (of palms or figures) at the corners and central apexes. The roof corners also carried lion-headed spouts to drain away water.

PARTHENON DECORATIVE SCULPTURE →

The temple was unprecedented in both the quantity and quality of architectural sculpture used to decorate it. No previous Greek temple was so richly decorated. The Parthenon had 92 metopes carved in high relief (each was on average 1.2 m x 1.25 m square with relief of 25 cm in depth), a frieze running around all four sides of the building, and both pediments filled with monumental sculpture.

The subjects of the sculpture reflected the turbulent times that Athens had and still faced. Defeating the Persians at Marathon in 490 BC, at Salamis in 480 BC, and at Plataea in 479 BC, the Parthenon was symbolic of the superiority of Greek culture against ‘barbarian’ foreign forces. This conflict between order and chaos was symbolised in particular by the sculptures on the metopes running around the exterior of the temple, 32 along the long sides and 14 on each of the short. These depicted the Olympian gods fighting the giants (East metopes - the most important, as this was the side where the principal temple entrance was), Greeks, probably including Theseus, fighting Amazons (West metopes), The Fall of Troy (North metopes), and Greeks fighting Centaurs, possibly at the wedding of the king of the Lapiths Perithous (South metopes).

The frieze ran around all four sides of the building (an Ionic feature). Beginning at the southwest corner, the narrative follows around the two sides, meeting again at the far end. It presents a total of 160 m of sculpture with 380 figures and 220 animals, principally horses. This was more usual for a treasury building and perhaps reflects the Parthenon’s double function as a religious temple and a treasury. The frieze was different from all previous temples in that all sides depicted a single subject, in this case, the Panathenaic procession which was held in Athens every four years and which delivered a new, specially woven robe (peplos) to the ancient wooden cult statue of Athena housed in the Erechtheion. The subject itself was a unique choice, as usually scenes from Greek mythology were chosen to decorate buildings. Depicted in the procession are dignitaries, musicians, horsemen, charioteers, and the Olympian Gods with Athena centre stage. To mitigate the difficulty in viewing the frieze at such a steep angle from the narrow space between cella and outer columns, the background was painted blue and the relief varied so that the carving was always deeper at the top. Also, all of the sculptures were brightly painted, mostly using blue red and gold. Details such as weapons and horses reigns were added in bronze and coloured glass was used for eyes.

THE MOST IMPORTANT SCULPTURE WAS NOT OUTSIDE BUT INSIDE THE TEMPLE

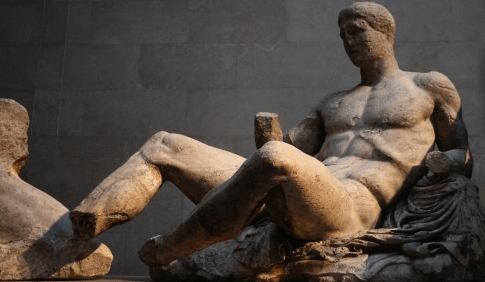

The pediments of the temple measured 28.55 m in length with a maximum height of 3.45 m at their centre. They were filled with around 50 figures sculpted in the round, an unprecedented quantity of sculpture. Only eleven figures survive and their condition is so poor that many are difficult to identify with certainty. With the aid of descriptions by Pausanias of the 2nd century AD, it is, however, possible to identify the general subjects. The east pediment as a whole depicts the birth of Athena and the west side the competition between Athena and Poseidon to become the patron of the great city. One of the problems of pediments for the sculptor is the diminished space at the corners of the triangle. Once again, the Parthenon presented a unique solution by dissolving the figures into an imaginary sea (e.g. the figure of Okeanus) or having the sculpture overlap the lower edge of the pediment (e.g. the horse head).

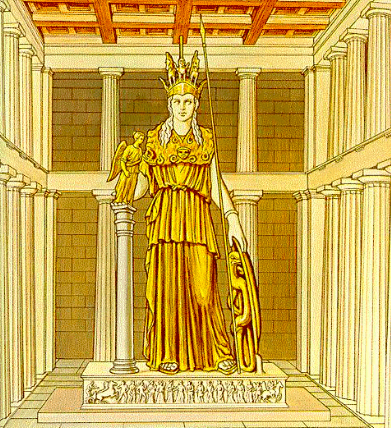

STATUE OF ATHENA→

The most important sculpture of the Parthenon though was not outside but inside. There is evidence that the temple was built to measure in order to accommodate the chryselephantine statue of Athena by Pheidias. This was a gigantic statue over 12 m high and made of carved ivory for flesh parts and gold (1140 kilos or 44 talents of it) for everything else, all wrapped around a wooden core. The gold parts could also be easily removed if necessary in times of financial necessity. The statue stood on a pedestal measuring 4.09 by 8.04 metres. The statue has been lost (it may have been removed in the 5th century AD and taken to Constantinople), but smaller Roman copies survive, and they show Athena standing majestic, fully armed, wearing an aegis with the head of Medusa prominent, holding Nike in her right hand and with a shield in her left hand depicting scenes from the Battles of the Amazons and the Giants. A large coiled snake resided behind the shield. On her helmet stood a sphinx and two griffins. In front of the statue was a large shallow basin of water, which not only added the humidity necessary for the preservation of the ivory but also acted as a reflector of light coming through the doorway. The statue must have been nothing less than awe-inspiring and the richness of it - both artistically and literally - must have sent a very clear message of the wealth and power of the city that could produce such a tribute to their patron god.

The Parthenon serenely fulfilled its function as the religious centre of Athens for over a thousand years. However, in the 5th century AD, the pagan temple was converted into a church by the early Christians. An apse was added to the east end which required the removal of part of the east frieze. Many of the metopes on the other sides of the building were deliberately damaged and figures in the central part of the east pediment were removed. Windows were set into the walls, destroying more parts of the frieze, and a bell tower was added to the west end.

LATER HISTORY →

In its new form, the building survived for another thousand years. Then in 1458 AD the occupying Turks converted the building into a mosque and so added a minaret in the southwest corner. In 1674 AD a visiting Flemish artist (possibly one Jacques Carey) took drawings of much of the sculpture, an extremely fortuitous action considering the disaster that was about to strike.

In 1687 AD the Venetian army under General Francesco Morosini besieged the acropolis which had been occupied by Turkish forces who used the Parthenon as a powder magazine. On the 26th of September, a direct hit from a Venetian shell ignited the magazine and the massive explosion ripped apart the Parthenon. All the interior walls except the east side were blown out, columns collapsed on the north and south sides, carrying with them half of the metopes. If that wasn’t enough, Morosini further damaged the central figures of the west pediment in an unsuccessful attempt to loot them and smashed to pieces the horses from the west pediment when his lifting tackle collapsed. From the rubble, the Turks cleared a space and built a smaller mosque, but no attempt was made to gather together the fallen ruins or protect them from any casual artefact robber. Frequently, in the 18th century AD, foreign tourists helped themselves to a souvenir from the celebrated ruin.

It was in this context of neglect that Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, paid the indifferent Turkish authorities for the right to take away a large collection of sculpture, inscriptions, and architectural pieces from the Acropolis. In 1816 AD the British Government bought the collection, now known as the Elgin Marbles, which now resides in the British Museum of London. Elgin took away 14 metopes (mostly from the south side), a large number of the best-preserved slabs from the frieze (and casts of the rest), and some figures from the pediments (notably the torso sections of Athena, Poseidon, and Hermes, a reasonably well preserved Dionysos, and a horse head). The other pieces of sculpture left at the site suffered the fate of exposure to weather, and particularly in the late 20th century CE, the ruinous effects of chronic air pollution.

Indeed, it was not until 1993 AD that the remaining frieze slabs were removed from the exposed ruin for what is said to be ‘safer keeping’. However, the most important pieces now reside in the Acropolis Museum, a purpose-built state-of-the-art exhibition space which opened in 2011 AD and stands in full view of the ruined temple just 300m away, still majestically dominating the skyline of Athens. Pericles had made no idle boast then when he emphatically stated that ‘...we shall be the marvel of the present day and of ages yet to come.

*This article was written by Mark Cartwright, “Parthenon,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, last modified October 28, 2012, https://www.ancient.eu /parthenon/.

*Mark holds an M.A. in Greek philosophy and his special interests include ceramics, the ancient Americas, and world mythology.

Statue of Athena Parthenos to be brought to life at the Acropolis Museum