A researcher at the University of Zagreb treated her breast cancer with an unproven therapy based on viruses that she cultivated in her lab.

A female scientist experimented on herself and was cured of breast cancer.

The researcher at the University of Zagreb, Beata Halasi, combated breast cancer with an unproven therapy based on viruses cultured in her lab.

In the summer of 2020, when she learned that her breast cancer had returned, she made a bold decision. As a virologist at the University of Zagreb in Croatia, she knew that researchers worldwide were testing virus-based cancer therapies to avoid the devastating side effects of conventional treatments like chemotherapy.

Halasi, whose livelihood involves studying viruses, decided to try some on herself.

With the approval of her oncologists, she experimented on herself and worked with colleagues to inject two types of viruses cultivated in a lab, as reported by the scientific journal Nature. Over several weeks, her treatment made the tumor shrink, eventually allowing surgeons to remove it.

In a study documenting her experiment, published in August in the scientific journal "Vaccines," Halasi and her colleagues mentioned that the "unconventional" therapy has kept her cancer in remission for nearly four years.

Bioethics experts told the Washington Post that they disagree with Halasi's decision to enter the historically controversial tradition of self-experimentation in medicine and publish her results. Although she had unique qualifications to weigh the decision and conduct the tests on herself, she might not have had the objectivity of a detached researcher since she was the subject of the trial. Her study on just one patient is unlikely to provide enough information to draw conclusions about the treatments she tested.

"From my perspective, self-experimentation is not fundamentally unethical," said Alta Charo, a professor emeritus of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. "It may be ill-advised. It could indeed be driven by an unrealistically high set of expectations… But I don't view it as inherently unethical."

Halasi and two of her co-authors did not respond to requests for comment, but Nature identified her as the researcher who was the study's subject. Halasi's study refers to her as "a 50-year-old self-experimenting female virologist" and is the only author fitting this description.

Research into using viruses to treat cancer dates back over a decade. The Food and Drug Administration first approved a form of oncolytic virus therapy — using viruses modified to specifically attack cancer cells — for skin cancer treatment in 2015. Since then, research has aimed to broaden the range of cancers this therapy can address. However, clinical trials for new treatments like this are limited, Halasi and her colleagues wrote in their study, often conducted on patients whose health might already be compromised by conventional treatments like chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Halasi, however, was in a different situation. She was several years past her 2016 breast cancer diagnosis and subsequent chemotherapy. She was a rare subject with the means and expertise to produce and administer her experimental viral therapy.

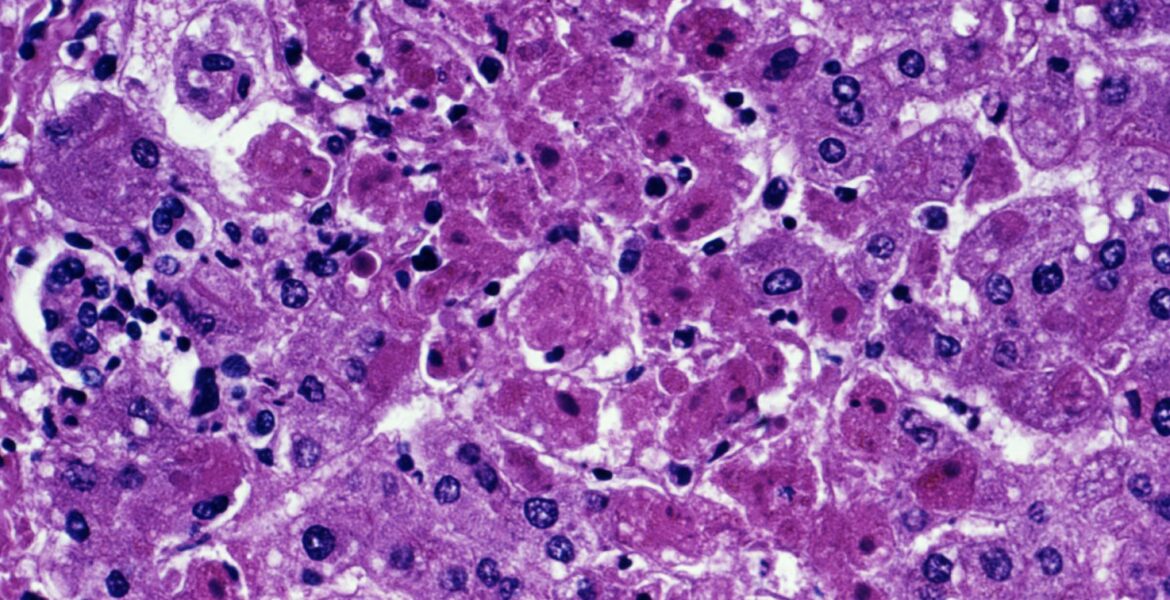

Her study used two types of viruses — a measles strain used in vaccines and the vesicular stomatitis virus, which affects animals — both produced in her lab, according to the study. The viruses were injected directly into the tumor at various intervals over about six weeks.

Approximately 11 days into the treatment regime, Halasi's tumor began to shrink and continued to reduce gradually until it was small enough to be surgically removed after the six-week injections concluded.

It was an extraordinary result, the study notes — the treatment had few serious side effects, except for one day when Halasi developed a fever, allowing surgeons to remove the tumor without further growth or spread within her body.

Halasi's breast cancer had recurred twice after her initial diagnosis in 2016. The study notes that since the viral treatment, she has been cancer-free for 45 months.

With her experiment, Halasi joins a long line of researchers who have tested medical theories on themselves. Their efforts have led to important medical discoveries — and in some cases, harm or death. Jesse Lazear, an American doctor studying yellow fever in the 19th century, died after allowing himself to be bitten by a mosquito to prove how the disease was transmitted. Peruvian medical student Daniel Carrión died in 1885 after infecting himself with Carrión's disease, which was later named after him.

Halasi's self-experimentation did not appear to be as dangerous as those fatal examples, said Hank Greely, director of Stanford University's Center for Law and the Biosciences. However, he emphasized that critics might still question whether a researcher in Halasi's position could provide the necessary consent to become a test subject and evaluate the potential benefits and harms of an experiment without bias.

In the past, it was considered a bad idea for doctors to treat family members or themselves because they lack the objectivity needed to do a good job, Greely explained. "The same applies to self-experimentation."

Halasi and her co-authors wrote that the study was not submitted to an ethics review board since it involved self-experimentation and that the subject was "fully aware of her disease and the available therapies" and "wished to try an innovative approach in a scientifically sound manner."