In the Iliad and the Odyssey, Troy appears as a great, widespread city defended by mighty walls and towers. The fortress enclosed an area extensive enough to provide room not only for its own large population but also for the numerous allies who assembled to help repel the Achaean aggression and found space for their chariots, horses, and all other equipment.

Some scholars have calculated that more than fifty thousand people could be accommodated as envisaged in the poems. The city had wide streets, and an open agora, or square, was laid out in the upper part of the citadel, outside King Priam's 'splendid palace'.

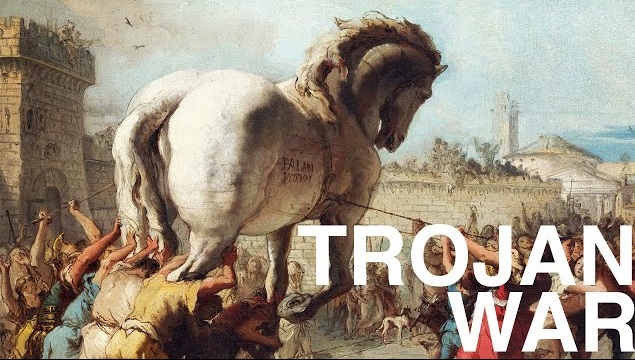

When the Achaean champions emerged from the famous wooden horse and captured Troy, Odysseus and Menelaus proceeded straight to that house. After a desperate struggle, they slew Deiphobus and recovered Helen, the beautiful.

In the Iliad, a Dardanian Gate is mentioned three times, presumably having been so named because it opened onto the road that led to Dardania, far away towards the south on the slopes of Mount Ida 'with the many springs'.

In one passage, the goddess Hera derides the Achaeans as helpless without Achilles, for when he was taking part in the struggle, the Trojans were frightened even to come out in front of the Dardanian Gate. Still, they boldly ventured to the ships now that he was absent.

Hector vainly sought to reach the shelter of this same Dardanian Gate each time he passed it as he fled before his pursuer, Achilles, three times around the walls of Troy.

And when Hector was slain, and Achilles dragged the body in the dust behind his chariot, it was from the Dardanian Gate that Priam wished to go forth to plead for honourable treatment and was with difficulty held back by his own people.

Although the Homeric poems provide no systematic description of the city, some - if not much - authentic information is undoubtedly preserved and frequently attached to one name or the other, Ilios or Troy. Troy is a 'broad city', 'with wide streets'; it has 'lofty gates' and fine towers'; it is a 'great city', 'the city of Priam', 'the city of the Trojans', and it also possesses - 'deep rich soil'. Ilios is 'holy' and 'sacred'; 'steep', 'sheer', and 'frowning'; but a 'well-built' city, 'comfortable to live in', though 'very windy'; it is likewise lovely', and it 'has good foals.'

The possession of good horses and the ability to tame them thus evidently came to be regarded as notable characteristics of the people of Troy.

All these casual, scattered bits of information about Troy and the Trojans (and about the Achaeans) that may be gleaned from the Homeric poems must be revised to what one might desire. It is mainly of a general and typical nature, such as any poet might freely imagine about any royal stronghold, king, and people. On the other hand, many items of detailed and distinctive knowledge and memory seem unlikely to have been independently invented by pure poetic fancy.

The brilliant achievements of several men of outstanding ability and genius have profoundly affected the views that scholars must now take regarding Homer and Homeric problems as well as the history of the Late Bronze Age in the Aegean. Most spectacular, perhaps, was Michael Ventris's discovery in June 1952 that the clay tablets from Knossos and Pylos, inscribed in the Linear B script, are documents written in an early form of Greek. Thus, the Hellenic language is shown to have been used in a Mycenaean palace.

Martin Nilsson had already long ago pointed out that almost all the great concentrations of Greek myths cluster about the palaces and populous cities that flourished in the Mycenaean Age, convincingly demonstrating that the origin of Greek mythology must go back to that era.

It can no longer be doubted that there really was an actual historical Trojan War in which a coalition of Achaeans, or Mycenaeans, under a king whose overlordship was recognised, fought against the people of Troy and their allies.

Folk memory may have exaggerated the magnitude and duration of the struggle in later times, and the numbers of the participants have been very overgenerously estimated in the epic poems.

Many major as well as minor incidents were undoubtedly invented and introduced into the tale in its course through the centuries.

But the internal evidence of the Iliad itself, in the abundant structural and linguistic survivals it contains, is sufficient, even without the testimony of archaeology, to demonstrate not only that the tradition of the expedition against Troy must have a basis of historical fact, but furthermore that a good many of the individual heroes - though probably not all - who are mentioned in the poems were drawn from real personalities as they were observed by accompanying minstrels at the time of the events in which they played their parts.

By A. Jones

READ MORE: Smyrna: The History of Asia Minor's Greatest Greek City.