The Parthenon Marbles, or more commonly but mistakenly known as the "Elgin Marbles", will be "much better preserved" if they remain in the British Museum, according to a renowned Greek historian.

Acquired from the Acropolis of Athens by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century, the 2,500-year-old statues are one of the museum’s most prized exhibits. But under plans drawn up by its chairman George Osborne, they could soon be sent back to Greece.

Dr Dimitris Michalopoulos, a former director of the Athens City Museum, argued that the disputed artifacts should remain in Britain, reported the Daily Mail.

"As I am fairly acquainted with Greek museums, I am convinced the Elgin Marbles are much better preserved in the British Museum than in any Greek one," the academic said.

According to the 70-year-old Athens-born historian, if the statues were sent to Greece on a loan basis, they would "never be returned" to the UK.

"I think British public opinion, in a manifestation of traditional British gallantry, is henceforth inclined to give them back to Greece. Nonetheless... the matter has an outstanding political aspect, let alone the legal, moral and religious ones," Michalopoulos added.

Greece has been calling for the return of the marbles for decades, stolen when the Mediterranean country was still under Ottoman occupation.

UK law prevents the British Museum giving away objects in its collection. But former chancellor Mr Osborne is understood to be in talks to loan the statues in exchange for other ancient artworks.

The British Museum said "constructive discussions are on-going". A government spokesman said: "The Parthenon Sculptures are legally owned by the trustees of the British Museum. Decisions relating to its collections are a matter for the trustees."

George Osborne – former UK chancellor and now chair of trustees at the British Museum – is reported to have negotiated the repatriation of the 2,500-year-old Parthenon marbles to Athens.

The deal, struck with the Greek prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, is not yet finalised. But it is thought that the sculptures will leave London “sooner rather than later” and it is planned that the British Museum will receive some ancient artefacts in return.

Early in the 19th century, the marbles were removed from the Parthenon by employees of Lord Elgin, then the British ambassador to the Ottoman empire. There is evidence that he wanted them to decorate Broomhall House, his estate in Scotland.

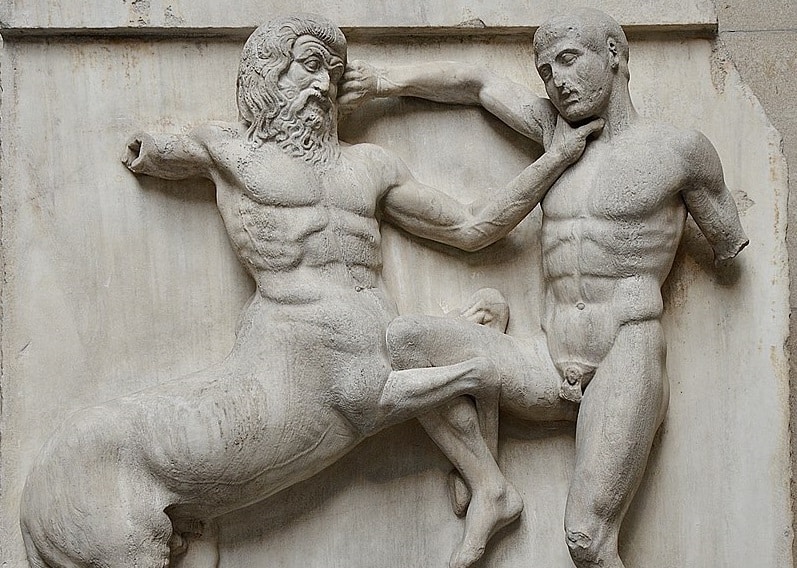

But Lord Elgin ran short of cash. After extended bartering, he eventually sold the sculptures, images of both gods and mythic battle, to the British government for £36,000 – much less than the costs he incurred in removing them from the Acropolis.

The sculptures were deposited in the British Museum, under the care of its trustees.

Last year, around the same time that Osborne’s negotiations started, the Greek prime minister had tabled repatriation as an item for discussion at a Downing Street meeting with Boris Johnson.

Whatever the backroom role of the British government, repatriation would not be possible without Osborne’s positive support. This is true, even while the former chancellor’s motivation might not be entirely selfless.

He now – like Lord Elgin – has the chance to associate his name with the artworks in perpetuity.

This potential personal ambition is not legally straightforward. The British Museum is formally a charity and Osborne must put the best interests of the organisation before all else. He must account for any negative consequences flowing from repatriation.

The issue is not clear cut. Although the museum will lose its prize exhibit, and may have less visitors, the return of the marbles will generate intense press publicity – and perhaps some goodwill – around the world.

READ MORE: Thessaloniki Metro: Impressive images from the excavations of the ancient city.