Identity, kaimo (regret), family secrets. The road not taken. The split-second life presents you with the fleeting chance to divulge information that can change a life. These are concepts that have fascinated me, and they have coloured Greek Australian scientist turned author’s Peter Papathanasiou’s life with striking hues. At times distinct, at times a breathtaking blur of shades interwoven together.

At the age of 25 years old, he was living the life of a dedicated, studious, scientist, spending endless hours in the lab. Meticulous in his methodology and with the ethic of a workaholic. When his mother beckoned him for a talk one afternoon, he sensed it would be about something important. As he beheld her sitting on the edge of her bed, feet atop the blue rug which had travelled thousands of kilometres with his mother when she had arrived, he did not expect to find out that she was not his biological mother. That the woman he had called ‘mama’ his whole life was, in fact, his aunty who had officially adopted him from her brother and his wife. At that time both his biological parents had died, and with their passing, the opportunity for Papathanasiou to meet them and get to know them lost forever.

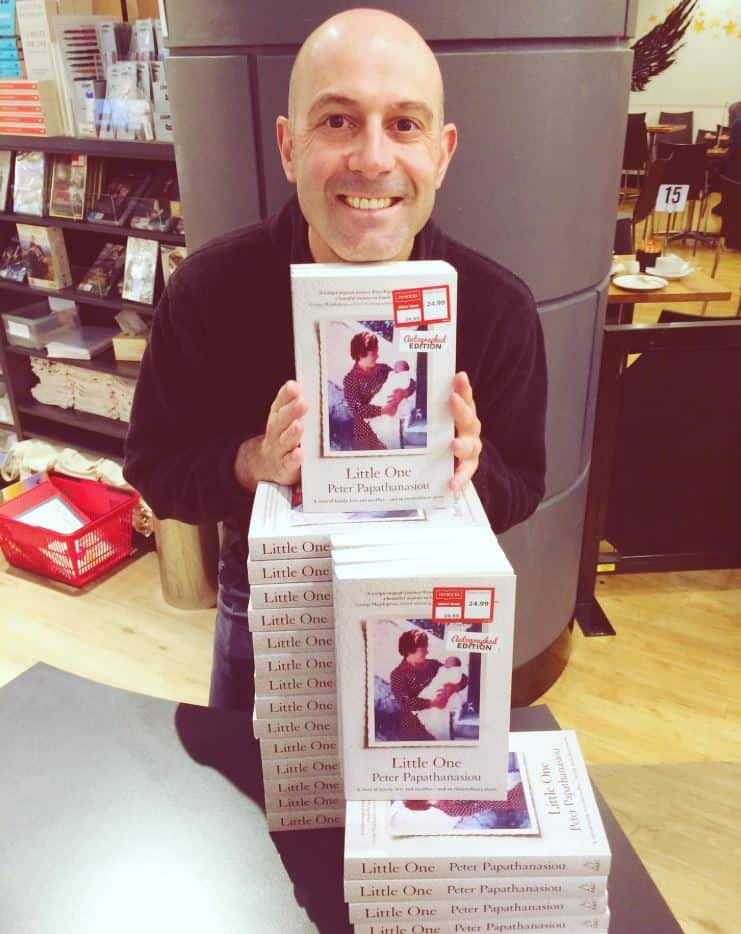

Channelling his emotions and experiences into writing a memoir led to a career change. With his book, Little One came a love of writing and he has since dedicated his time to becoming a writer. Little One does not read like a debut novel, rather the works of a seasoned career writer. With its perfect prose soaking up the events and emotions like a sponge to store for the reader, and imagery so bright it remains in your mind long after you have finished the story, Papathanasiou’s decision to allow his every emotion and thought to be recorded so freely and publicly makes for compelling reading. His writing style is a joy to read, and his life events have all the markings of an epic film.

After chancing upon his story, I could not wait to interview him. The anticipation of peeling away the layers of meaning that have informed his journey and his writing coursed through my veins. From the moment I read about his family and life, I was hooked. It is a moving tale of love, family, sacrifice, tenacity, endurance, forgiveness, inspiration. It is filled with sadness and hope and tinged with bittersweet tones that ultimately make way for joy.

According to Papathanasiou, writing Little One was important for several reasons. “First, because I enjoy writing and love reading, and always have ever since I was at primary school,” he says. “Second, I wanted to honour the sacrifice and devotion of my parents, both my adoptive parents in Australia and my biological parents in Greece. Third, I wanted to document the story for my own children in the hope they might read it when they grow up and fully appreciate where they came from, their ancestors.” Lastly, he wrote it to inspire other people to write their own family stories. “There are so many interesting stories from the past, secrets, and mysteries in people’s families,” he says. “Even if you don’t find a publisher, you can self-publish these days. Either way, I think it’s important to write these stories down somewhere so they are documented and not lost forever.

“Little One was about a significant event in my life, but there was no doubt many other events in the history of my family that are now gone, buried with the people who lived them. And you never know – there may also be a publisher who is very, very interested in your story.”

In recording these true-life events, Papathanasiou has managed to paint a complete picture of each backdrop. From the detailed historical milestones in Greece to the village traditions, even the fragrances, and colours of the countryside. The level of detail in the descriptions grants the reader with education while simultaneously transporting them into the scene with ease and imagination.

“Researching Little One was extensive and came through a number of different avenues,” Papathanasiou says. “Of course, it helps to have lived the story, so it began with writing notes over many years about the events that I experienced and my associated emotions. Where I hadn’t taken notes, I looked up old emails and letters, and also spoke with my friends. Speaking with my adoptive mum Elizabeth – my mum – was also very important since I decided to write half the book in her voice; there are many chapters which precede my birth in 1974, and I found it most effective to write those in my mum’s voice as a first-person narrator (‘I’) than as a third-person narrator (‘Elizabeth’). I found it easiest to research Mum’s side of the story by sitting with her and recording her recollections on a tape recorder as she spoke over numerous sessions.”

Where there were gaps in her story, Papathanasiou spoke with his brother Georgios in Greece. For historical events like the 1923 Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey and the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus, he researched using reference books and reputable internet sources. “Travelling to Greece on many occasions was also crucial to capturing the finer details like the landscape, the township, and local residents,” he says. I was ‘that guy’ walking around with a notebook in hand!”

‘Kaimo’(regret) has permeated Greek culture for generations and is handled eloquently in Little One. Sympathizing with the characters, it is inevitable to ponder what is the best way to resolve this heaviness of kaimo. I wanted to know what Papathanasiou thinks helped his entire family work through it?

“I think a life without the weight of kaimois impossible to live; every one, in one way or another, regrets something that they either did or didn’t do at some point in their lives, whether it be a decision about a personal relationship or a job opportunity or something else,” he says. “Sharing our regrets is a way of ‘cleaning out our emotional closets’ in the hope of reconciling unresolved issues. Writing a book could potentially be seen as the ultimate way by which to share one’s kaimo, and many people have asked me if I wrote Little One as a form of therapy, which I completely understand, although that wasn’t my primary motivation.

“I think the main thing that helped my family work through its kaimo was the thought that despite the outcome of any one individual decision made across many generations, the heart was always in the right place. No one can see into the future, but you can look back at why certain decisions were made, and my family always seemed to be comfortable with the reasons, which came from a position of love and the desire to do good.”

Many documentaries and books about adoption such as Long Lost Family, have showcased the quest for identity. ‘Who am I?” “Where have I come from?”. This is an extra layer of identity to the issues grappled by many second and third-generation Greek Australians who often find themselves in a tug of war between their Greek identity and their Australian identity. This is the same for migrants all around the world who have established new lives for themselves in a foreign country.

As the son of migrants, and also having processed the information of his adoption, Papathanasiou is an ideal candidate to answer the question of what he has learned about identity. “This is a very good question. When I was 24 years old and discovered I was adopted, this threw up all manner of questions about who I was and who I could’ve been “ he says. “Add to this was the fact that I had grown up in Australia from a Greek family, which meant I had one foot in each country, with an identity that could’ve been considered ‘hyphenated’ (Greek-Australian). And lastly, being in my mid-20s was still a time in life when I was working out my future and emerging as an adult. As you can see, there were a lot of balls in the air!

“Now, it’s some 20 years later, and the balls have generally landed. I travelled to Greece on many occasions to meet my two older brothers – the two versions of myself that I could’ve been had I not been adopted – and realised that although we were similar in some respects, we were also clearly different in others. Being older, I’m now also more mature, and so less concerned with trying to pinpoint my position in the universe.

“In modern-day Australia, those with a Greek heritage are now also less conspicuous than they were last century; the cultures have blended, and another generation has emerged, which I see with my own children. In short, I have learned that identity is who I am, and it doesn’t require a precise label because it’s multi-faceted and complex.”

Papathanasiou is open about the fact that he could’ve done a few things differently. In the book, he cites the time where, as a child, his aunt in Greece (which was his biological mother, unbeknownst to him at the time) asked to speak to him on the phone and he refused not realizing the significance. I am curious if the clarity of hindsight has changed his emotions when reflecting on these events. “When my mum first told me the truth behind my adoption, I experienced a wide range of emotions including shock, anger, deception, fear, regret, intrigue and excitement,” he says. “Over time, these emotions have diminished in intensity; as the old saying goes, time is a great healer. But that also came with educating myself and finding out more about my family story.

“My emotions were all too raw in 1999 when I found out the truth, and two decades is a long time since then, and has included four trips to northern Greece to spend time with my brothers and hometown. Above all, the emotion which now endures is that of connection and hope. My brothers and I are close, which is something I’m grateful for, and which I know both sets of parents would be proud to see. And Mum is stoic and now nearly 90 years old. Any resentment that I felt towards her in the heat of the moment when I was in my volatile early 20s is now gone, replaced by awe and respect for all that she did.”

With Little One proving to be a cathartic experience, I ask if he experienced any epiphanies throughout the writing process. “Epiphany is such a weighty word that I am reluctant to use,” he says. “But I definitely discovered some significant details that I didn’t know about my family through writing Little One which came from being inquisitive for the purposes of writing the book – if it weren’t for that, I wouldn’t have asked otherwise. From that perspective, the book definitely served as a vehicle by which to find out more about my family; an excuse, if you will.

“On reflection, there were some major revelations. Historically, it was my grandparents’ harrowing trek out of Turkey as Orthodox refugees during the 1923 Population Exchange; I hadn’t realised I had something like that floating through my veins. I also hadn’t realised how the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974 impacted my baptism and return to Australia, but it makes complete sense given it happened only a month after I was born and Greece went into lockdown. And personally, it was crushing to hear my brother describe my biological family’s emotions when my adoptive mum took me to Australia as a six-month-old: ‘No one spoke for three days after you left.’ It was like a period of mourning as if I had died. This was despite my adoption being agreed to by all parties – my biological family still wasn’t prepared for the vacuum I left when I was taken away.”

Considering the magnitude of switching from scientific to creative, I am eager to uncover what inspires Peter. “I like to write things with substance. In other words, I’m usually inspired to write about topics and themes that touch upon the issues that make us human,” he says. “This is another reason why writing a book about family, identity, and adoption resonated with me, and why I’ve also written and published a number of short articles on subjects like climate change, anxiety, sleep, parenthood, music, body donation, animal experimentation, stray animals, religion and migration. The book still has to be entertaining, compelling and well-executed, but I find that the most satisfying books that I read are usually those that make me feel like I have been taken on a journey and learned something about the world through a series of characters and situations.

“Escapism has its place too, and I enjoy those stories as much as the next person! But I am more inspired by the world around me and committed to, hopefully, making it a better place through writing.

Since its release last year, there has been an overwhelming reaction to Little One from both readers and reviewers, which exceeded Papathanasiou’s expectations. His mum’s iconic blue rug that punctuates significant events in the book has even taken on a life of its own, with readers requesting to see it. The rug is still at her house now and after many reader requests, Papathanasiou tweeted a photo from his account (@peteplastic) last July, to the excitement of his followers.

This publicity has also been prevalent in the UK, as the book was published in both countries (the UK title is Son of Mine and features a different cover). Shortlisted for the 2012 Man Booker Prize, author Alison Moore described Little One as ‘absorbing and beautifully written’. Writing for the Literary Sofa blog, Isabel Costello described Peter as ‘someone who not only delivers beautiful prose but who writes with honesty, empathy, and willingness to show vulnerability as well as courage.’ “She also noted the memoir is ‘a welcome antidote to the culture of toxic masculinity’, which was something I really liked,” Papathanasiou says.

The book is written in two narratives that of his mum’s (Elizabeth) and Papathanasiou’s. “Mum is understandably proud of me,” he says. “She watched me for years writing and editing and submitting and facing setbacks; to see her child finally rewarded for all that effort made her very happy. But Mum was also fairly nonplussed – in her mind, the events took place were so long ago and were so unremarkable (to her) that she wonders why all the fuss exists now. She never did what she did for any attention – all she wanted to be was a mother – so to have her story thrust into the spotlight leaves her shaking her head a little. But that’s just Mum. She was never much of a bookworm to fully appreciate books herself, although she admired anyone who could write one. Unfortunately, she hasn’t read it as her written English is poor so I am hoping that a Greek publisher will one day publish the book and have it translated into a language that she can actually read. I would love that, and I know she would too. I’ve had many readers asking me if the book is available in Greek, and I suspect there would be great interest in Greece given that Little Oneshowcases the culture so well and also highlights a successful immigration story.”

There have been many highlights along the way, including having the opportunity to speak about the story at book launches and literary events. But for Peter, the best feeling of all is when he receives messages of appreciation from readers. “It’s then that you realise you’ve made a connection and touched someone in a real way. At times, while I was writing and editing, I doubted whether anyone would ever want to read what I was spending so long trying to craft. I know that’s not an unusual feeling for most writers. But when you receive messages of appreciation and praise from readers, when someone has gone out of their way to not only read your book but then reach out to you and share their feelings, it makes all those hours of work and moments of self-doubt worthwhile.”

With Little One serving up such an enormous platter for the reader to feast on, from historical facts to culture, to identity, and navigating the full spectrum of emotions from heartbreak to contentment, I ask Papathanasiou what he would like readers to take away from the book. “First, the story itself, which shows a portrait of a family who are flawed like most families, but who worked to find their way forward through hard work, sacrifice, and love,” he says. “It’s a story about overcoming adversity, unfamiliarity and doubt. It’s a book about parenthood – what it means, and what some people will do for it. And second, I hope readers are inspired to research and write their own family stories, or indeed, just their own life story. As I mentioned earlier, if people don’t commit these incredible personal histories to the written word, there’s a risk that they will be lost forever. And sharing such true stories can be especially powerful because they help us realise that we’re all human and that we’re not alone as we try to navigate all the challenges that life throws at us.

I am elated to hear that Papathanasiou is planning on writing another book this year, which will be a novel. “It would be fantastic to be able to follow my own life story with a fictional story that I have carefully plotted to be interesting and compelling, and which covers themes for which I am equally passionate.”

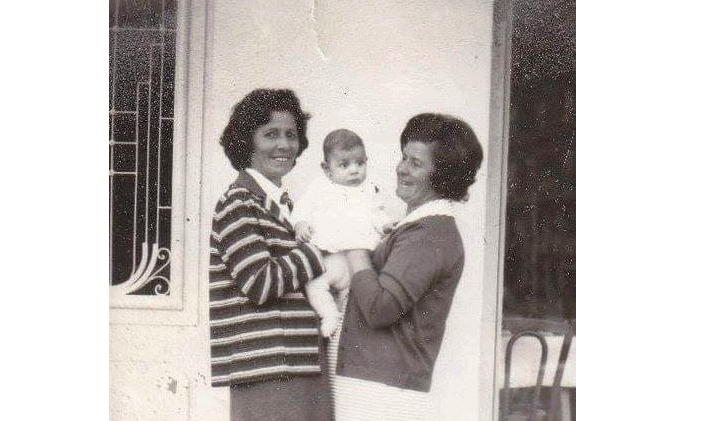

Peter as a baby with his biological aunts Sultana on the left and Elizabeth, who became his adopted mother, on the right

Until then you can savor the excerpt below or purchase the book online, including at: allenandunwin.com

*Special excerpt can be found here: verityla.com