Tobias Christopher Hautekiet

Confinement is isolating and gives the sense that everything has come to a stand-still, but this once aristocratic Kypseli neighbourhood revealed a lot about itself during lockdown, and how it might change.

Kypseli is a story that sounds familiar. It was once a prestigious place to live, with its neoclassical and art-deco flats, but from the 80’s onwards it became a diverse and working-class neighbourhood as wealthier Athenians moved to the suburbs.

More recently, gentrification started settling in: it is often cited as an up-and-coming and trendy place, while the politics of nearby anarchist Exarcheia has started to spill over. Those in lockdown in Kypseli may have caught a glimpse of what it might look like in the future.

A street asleep

Fokionos Negri is a pedestrian avenue running through Kypseli's heart, filled with bars, tavernas and cafes. Back in normal times, it never slept: during the day you would hear children screech and laugh, and at night music booming and people chatting. When the Greek government announced on the 14th of March that cafes and bars had to close due to the public health crisis, it all changed. During your daily walk, you saw windows with shutters and rooms with empty chairs. You heard sirens and the police’s tannoy system ordering people to leave the area, and then there was silence. The socially-distanced lines at supermarkets got longer, and Greeks would have passionate arguments about who was jumping the queue. The front-pages of newspapers were plastered with “everyone stay home”.

But lockdown was easier with balconies, and the neighbourhood’s residents would sit in the sun and peer at each other. In the evenings, a bouzouki-player would twang strings and wail to the empty streets as they darkened. Walks were best at night, because there were fewer people and the lamp-lit squares were pretty even when mostly deserted.

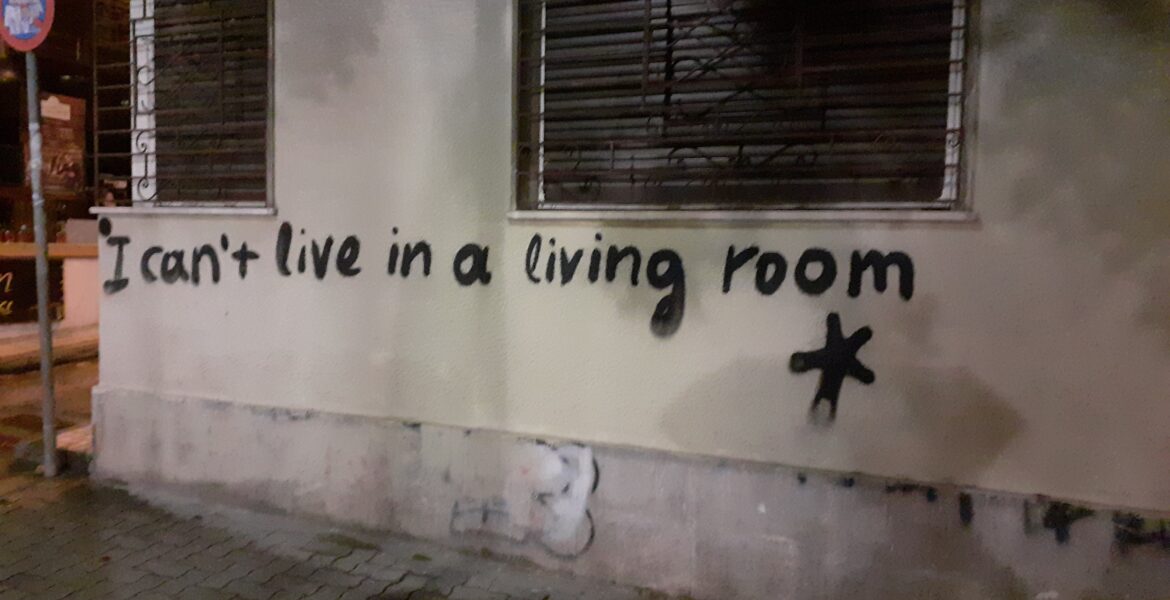

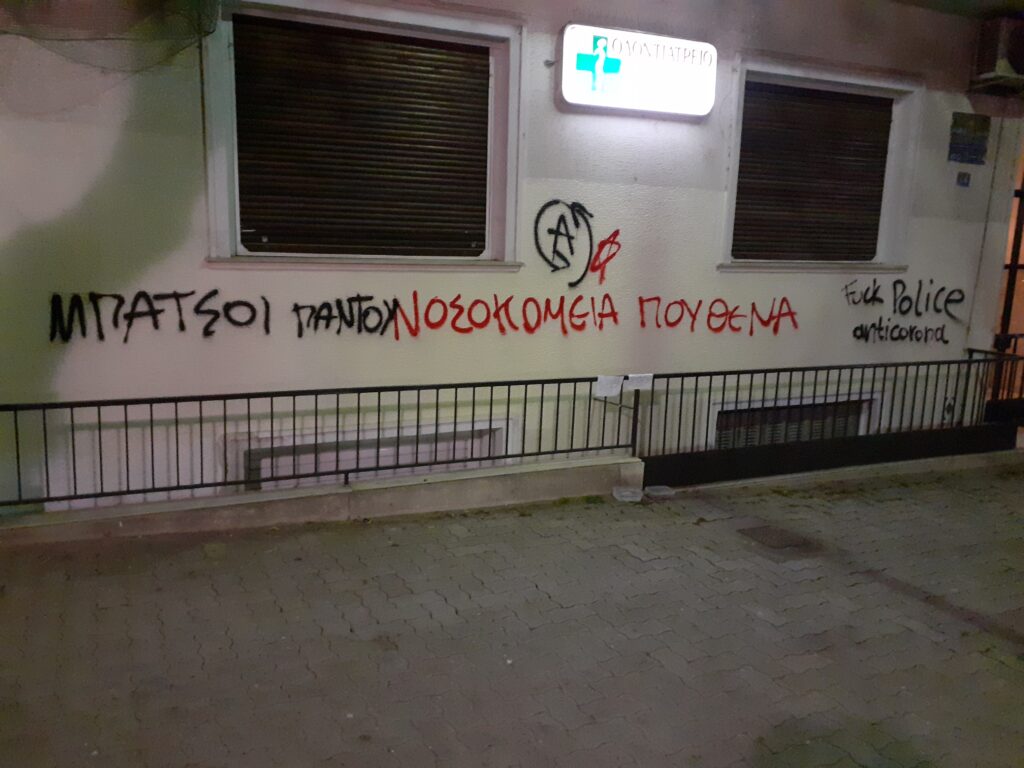

It did not take long for the walls to start talking. A few nights into the strict lockdown which started on the 23rd of March (which required permission slips for all trips outside), graffiti appeared. “I can’t live in a living room” was sprawled on two apartment buildings squeezed between the shops. Athens’ grass-roots activists quickly reacted to losing their home: the streets. A scribble under a dentist’s flashing green cross read “cops everywhere, hospitals nowhere”.

Waking up

Easter is taken seriously in Greece. Usually a time of big public gathering, there were worries over whether people would stick to the rules. Late at night on April 19, everyone appeared on their balconies with candles, and reassured each other they were all still there. It was a sweet scene, until the loud crashing flashes of fireworks lit up the sky. Because most people were not busy during the coronavirus lockdown, it felt like everyone was watching them together, and isolation stopped feeling like the right word.

Moving on

Measures started to lift on the 27th of April. In reality, even before then, the streets had loosened up as the neighbourhoods dogs needed walking. A busker played bella ciao and despacito on loop, people strolled around with takeaway ice-coffees. Musicians started teaming up, and came together to play well-loved songs in Greek, with little crowds gathering around them.

Although the moment when it really felt like lockdown came to an end, occurred on Friday the 8th of May. It was late and you could hear a crowd chanting. Everyone once again appeared on their balconies and peeked at the protestors. A collection of feminist groups made their way down Fokionos Negri, shouting in sympathy with the refugees still stuck in confinement or pushed back at the border. Some spectators clapped, others stared.

One of the most visible changes the lockdown brought to Athens was the police presence in Plateia Exarchion. Before quarantine, police did not enter the centre of the park, but were positioned around it. As of March, a squad of police is stationed at the Plateia. A spokesperson for the police told Kathimerini, the country’s biggest newspaper, that “anarchist groups have moved to the Plateia Agiou Georgiou and Kipseli generally, after the strengthening of police presence in Exarchia” and that they want to increase police presence to ensure “it does not become a new ghetto”. Lockdown is set to change things in a lot of ways, and that extends to the social topography of cities and neighbourhoods: it looks like the politics of protest and the police might shift to Kipseli, bringing this dense residential neighbourhood into the headlines.