He discovered the Minoan palace of Zakros on Crete.

Nikolaos was born on the island of Cephalonia but his parents moved to Heraklion Crete when he was very young and it was there that he received his primary and secondary education. Nikolaos and Heraklion proved to be a good fit.

He was, by all accounts a diligent and disciplined student who graduated from high school as the winner of the school’s gold medal for excellence. Even then the adjectives ‘modest’ ‘unassuming’ and ‘mild mannered’ were used to describe his personality.

Nikolaos went on to study literature and archaeology at the Philosophical School of Athens University. After graduation, he worked at the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion under one of archaeology’s superstars, Spiridon Marinatos.

He held a position there until 1935 when he moved to the mainland as curator (ephor) in Thebes – another fascinating centre of prehistoric Greece, this time Mycenaean.

All this before going to Paris in 1937 to obtain his doctorate at the École Pratique des Hautes Études.

When he returned to Greece in 1938 he took over from Marinatos as the curator (ephor) of the new Heraklion Archaeological Museum a position he would hold for 24 years until 1962.

This museum was remarkable for its fabulous contents but also because many of its architectural elements – colours, polychromatic marbles, and columns – echoed Minoan design. It was anti-seismic and had innovative skylights to highlight the exhibits: Bauhaus meets Minoan.

His long tenure there was rudely interrupted, by the Italian and German invasions – and thereby hangs a tale.

The Second World War and Greek Archaeological Treasures

In May of 1941, Platon was in Epirus, a soldier on the Albanian front. Germany had invaded Greek territory the previous month. Fearing for the artifacts in his beloved museum, Nikolaos was desperate to return to Crete, a seemingly impossible journey under the circumstances.

He used his connection with German archaeologist Kurt Gebauer at the German Archaeological Institute in Athens and obtained permission to fly to Crete! Two factors may have been key to the success of this surprising manoeuvre.

First, many Greek archaeologists had long associations with their German counterparts in Greece. In spite of the natural territorial sentiments of each archaeological school, archaeologists are a fraternity.

The German Archaeological Institute had been a part of Athenian life since its founding in 1874 and some of its members had Greek spouses. Gebauer’s wife’s mother happened to be Greek. That may have helped. Secondly, archaeologists are all preservationists at heart, perhaps another reason for Gebauer to help.

There may have been another factor as well. The preservation of ancient artifacts suited Nazi propaganda goals: the glories of ancient Greece played into their Aryan fantasy that Germans had descended from ancient Greeks.

In their arrogance, they may have assumed that since all of Greece’s treasures would be theirs in the near future, who guarded them in the meantime did not matter so much. Their certainty of ultimate victory is, to me, the only plausible explanation for the fact that so many Greek museum treasures which had been so carefully hidden by Greek museum personnel before the invasion, remained hidden until the war ended.

The order to hide the treasures had come from the Greek Ministry of Culture.

In October 1940, after the war had been declared, the Ministry had issued a letter to all museums to hide whatever they could. A great deal was accomplished in the six months before the Germans actually invaded.

Museum floors all over Greece were dug up, artifacts lowered, sand used as a buffer, and the floors then replaced. Other items were hidden in caves, secret storerooms, and private homes.

And so it happened that when the German occupiers sent their own experts to museums all over Greece, they found empty rooms.

The Heraklion Museum staff had complied with the Ministry’s directive to the best of their ability. Still, it is hard to believe that the Nazi’s, with their well-known torture tactics, could not have unearthed the secret of the hidden exhibits had it been a priority.

They may have been playing a long game, – waiting until their victory was assured and the population totally subdued before going after these missing treasures in earnest – something that thankfully never happened.

The German military pilfered whatever they could and even did a little excavating during the occupation. According to his son, Platon slept inside the Heraklion Museum to protect it from predators, especially the rapacious German general, Julius Ringel who had ensconced himself in Sir Arthur Evan’s home, the Villa Ariadne, at Knossos and was stealing whatever he could find for his personal collection.

Ringel was a ruthless man and Platon knew where all the treasures were buried. This was dangerous information to have. His determination and steadfastness in the face of the occupiers were truly heroic.

1945 and On

The museum suffered damage during the war. It was Platon who supervised the placement and re-exhibition of its contents so that it could reopen in 1952.

When the war ended, Platon was put in charge of all Cretan archaeological sites, a position he would hold until 1962. In 1958, he proposed a system of Minoan chronology based on the development of Minoan palaces.

He divided the Minoan period into Prepalatial, Protopalatial, Neopalatial, and Post-palatial periods. This system was employed along with Evan’s chronology which was based on pottery styles.

In 1960, there was a new direction. He was made director of the Acropolis Museum and the Athens area. It was a busy time since he was concurrently the field director of the excavation in eastern Crete in 1961 which unearthed the palace complex at Zakros, the find of a lifetime!

The Palace at Zakros

Others before Platon had speculated about the existence of a Minoan settlement in eastern Crete to complement the known palace complexes at Knossos, Mallia and Phaestos.

It made sense given what was known about the Minoan trading activities. In 1900 David Hogarth of the British School had begun excavations at Zakros and found artifacts pointing to a possible palace complex. But he did not find the palace itself. Nikolaos Platon did.

The palace was small, about a fifth the size of Knossos, but it still covered an area of 4,500 square metres and contained all of the rooms expected in a complex which was the commercial and religious hub of the community which surrounded it.

There were reception rooms, a room for religious rituals, storerooms with clay tablets (Linear A), and chambers for the ruler and his family. A paved road went from one of the Palace entrances to the commercial port.

Finds have indicated that Zakros traded with Africa and Asia. Locally-made pottery and other items were found in Cyprus, Egypt, and the Middle East.

The work of the excavators was not muddled by later buildings and the methods used in 1961 were more scientific than the earlier efforts of Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos, so much was learned at Zakros.

The first palace dated back to 1900 BC and it is likely that an earthquake caused it to be rebuilt 500 years later. When it, too, was destroyed, the site was abandoned.

In Athens

As curator of the Acropolis and its museum, his priority was to protect the site. This was a continuation of efforts that had been ongoing since the 1830s and mistakes had been made.

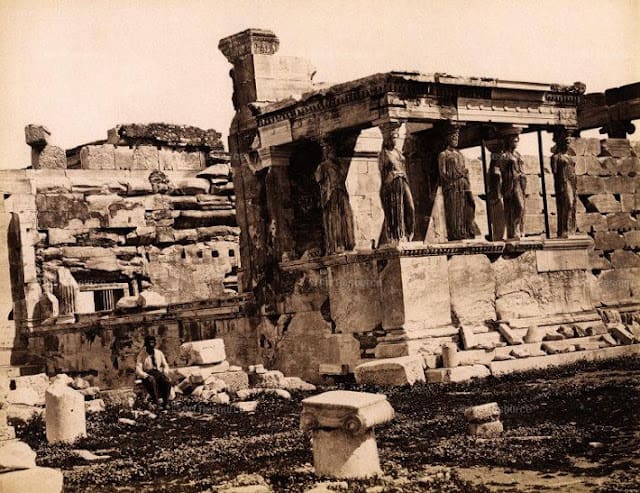

Apparently, he began with some work on the Karyatids, those stalwart maidens who had been doing service holding up the Erechtheion porch for well over two thousand years without a break. They had already lost one sister to Lord Elgin and were in desperate need of repair.

The situation on the Acropolis during his tenure was daunting because of the rusting iron used in previous repair efforts, pollution, and just plain errors of placement by earlier restorers.

He had an exhaustive archive made of what remained on the acropolis, restored what he could manage on a budget that was never enough and, in 1965, even conducted excavations behind the western end of the long Portico of Eumenes (6).

There he discovered a Mycenaean chamber tomb which has led to speculation that this area had been a Mycenaean cemetery which future generations had almost entirely obliterated.

Platon created the Commission for the Rescue of the Acropolis Monuments. He remained committed to this long term project and organized international conferences about the issue.

It would not be until 1975 with the formation of the interdisciplinary Acropolis Conservation Committee, and funding from the Greek government and European Union that the rock would get the attention it so needed and deserved. This project is still a work in progress but the Karyatids did get a good home in the New Acropolis Museum when it opened in 2009.

In 1965 Platon added the word ‘professor’ to an already full resume, teaching prehistoric archaeology at the University of Thessaloniki and, in 1974, at the university in Rethymnon, Crete.

Summation

To say that Nikolaos Platon was adept at multitasking would be an understatement. Along with the accomplishments described, he was also instrumental in the founding of

The Society of Cretan Historical Studies (SCHS) in 1951 and aided in the restoration of the Vikelas Library in Crete which had been damaged during the war.

He was knowledgeable about and taught Byzantine history as well. It never fails to amaze me, the range of scholars’ interests in the 19th and early 20th centuries before the present age of narrow specialization. His book, Zakros : The Discovery of a Lost Palace of Ancient Crete can still be found for sale on the Internet.

During his lifetime he was made a member of the Athens Academy and honoured by the Italian state for his contribution to archaeology.

He died in Athens in 1992.