The Greek revival style in Australian architecture and the reception of classical Greek ideas in Australia, Europe and globally, particularly in the built environment, were the central themes discussed by a panel of experts convened by the Executive Board of Greek-Australian Business Leaders at Parliament House in Sydney on 18 October 2022.

John Azarias, Chairman of Executive Board of Greek-Australian Business Leaders, welcomed the audience amongst whom was the Greek Consul-General in Sydney, Yannis Mallikourtis. He then introduced the State Minister for Infrastructure, Cities and Active Transport, Rob Stokes who acknowledged the town planning genius of Hippodamus of Miletus (fifth century BCE) and then paid tribute to the beautiful touches between Greece and Australia in terms of architecture and democracy stemming from the perfection that is the Parthenon.

John Azarias opened the formal proceedings by referring to the intellectual leap that the Greeks made in the 5th century B.C. and why the classical Greek achievement has been so willingly embraced and absorbed by an immense variety of cultures over many centuries.

Citing the historian Edith Hall that the Ancient Greeks had gone from Bronze Age seafarers to navigators of the Western mind, he emphasised that Greek belongs to a way of thinking as well as a profound respect for humanity.

Turning to home, John Azarias, as Co-Founder of The Lysicrates Foundation, noted that these sentiments had found a welcoming home in Australia in terms of both architectural and intellectual life. He drew on an early colonist, James Martin, who was inspired by the Greek ideal and had created a replica of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Sydney in around 1868. As the current Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, The Honourable A.S. Bell, has written, the monuments represented points of connection to the classical world and to the British world and was a way of satisfying civilisational yearnings that generation of colonists – whether migrants or born here – and many generations that followed being largely oblivious to the ancient indigenous civilisations that existed on these shores for thousands of years.

Greek echoes in an indigenous landscape.

Alastair Blanshard, Paul Eliadis Professor of Classics at the University of Queensland, was the first speaker and he discussed the international context of what he termed the “thrill of the new”.

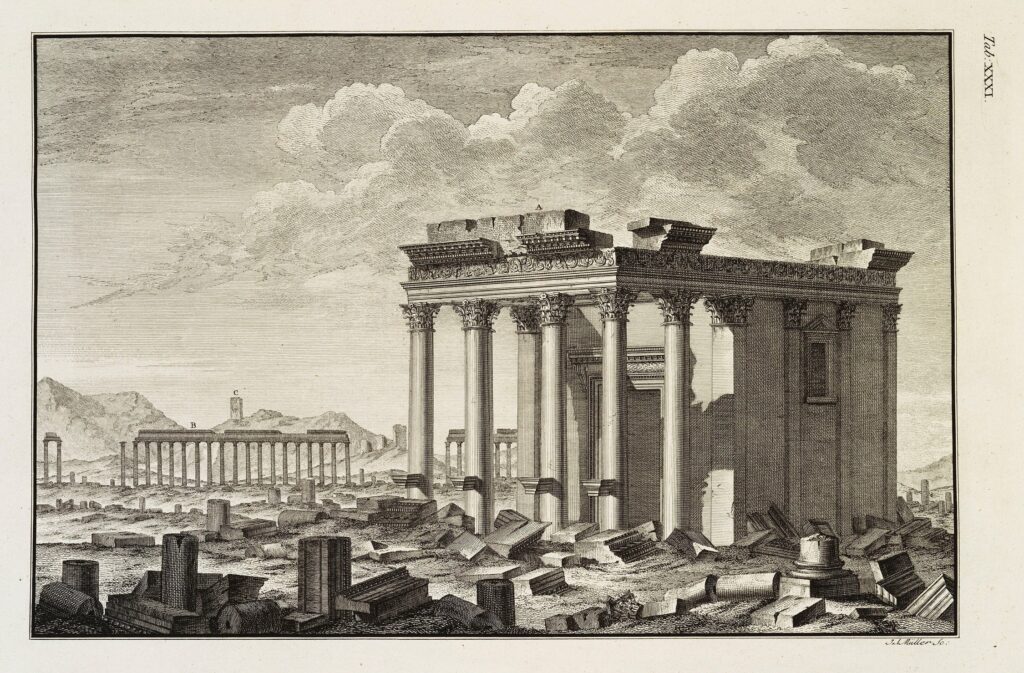

A major development was the rediscovery in the mid-18th century of the ancient city of Palmyra in Syria. Its noble ruins – as recorded by the renowned classical scholar Robert Wood – seized the public’s imagination and had a profound influence on classical taste. It inspired the Society of Dilettanti in London to look towards Greece and the Levantine on Grand Tours as Englishmen, notably scholars and intrepid travellers, were gradually reintroduced to Classical Greece and the Parthenon which, according to Blanshard, was and still is a “delight in architectural form”.

As J M Freeland, the author of Architecture in Australia has written, the Dilettanti Society had sent an expedition to measure and record the buildings of Greece as it saw Classical architecture as the “repository of all worthwhile architectural knowledge”.

Interest in Greek architectural forms also derived from James Stuart and Nicholas Revett’s seminal Antiquities of Athens which was published in 1762 although it was in their second volume produced in 1788 that contained their careful reconstruction of the Parthenon.

The neo-Classical revival had arrived as the new forms of architecture spoke to the Age of Revolution, staring with the American Revolution in 1765 and followed by the French in 1789, Haiti in 1791 and finally the Greek War of Independence in 1821.

Greek architectural forms and concepts were rediscovered. They were democratic in sensibility and embedded the ideals of the Enlightenment.

One of the earliest known examples of the Greek revival in Britain was the Greek Ionic style portico in the West Wycombe estate owned by Sir Francis Dashwood. It was built around 1770 and modelled on the Temple of Dionysos in Teos.

Another eighteenth century architectural delight was the Irish Parliament, reflecting that Greek architecture was both enlightened and cosmopolitan. The classical influence has permeated many governmental buildings such as the Temple of Justice in Valletta, Malta, the United States Supreme Court and the Montpellier Courthouse, amongst many.

The Greek Revival/Neo-Classical style also finds expression in the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne, completed in 1934. Based on the Parthenon in Athens and the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus this war memorial features two north and south facing porticos each incorporating eight fluted Greek Doric columns supporting a pediment with allegorical sculpture in high relief.

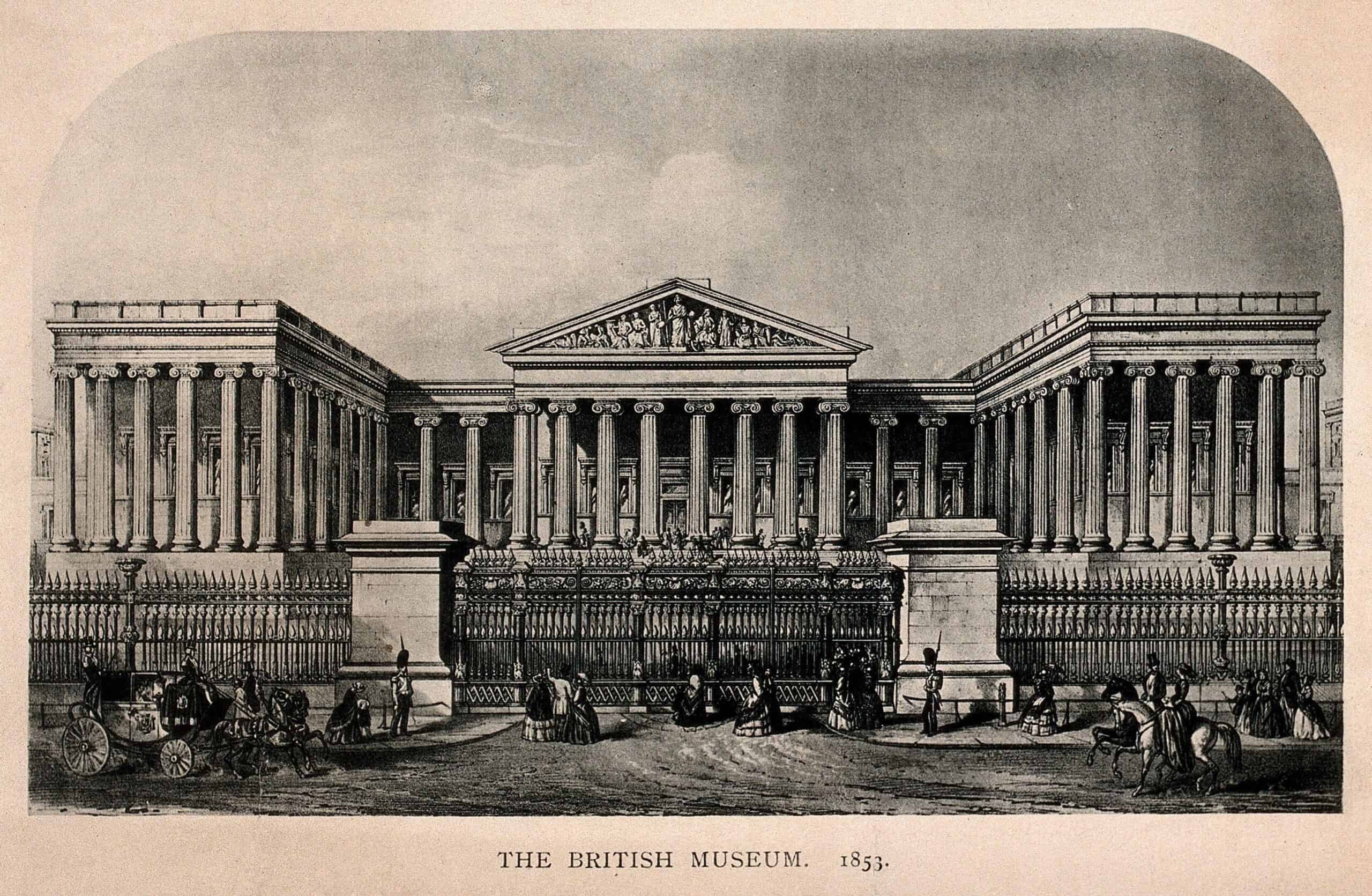

Ironically the British Museum, which holds the controversial Elgin collection of Parthenon Sculptures, was designed by Sir Robert Smirke, the government architect, with fluted Ionic columns and flanking colonnades and a synthesis of the orders of the Greek temples.

As Professor Blanshard noted, Smirke was an unabashed advocate of the Classical:

“How can I by description give you any idea of the great pleasure I enjoyed in the sight of these ancient buildings of Athens! How strongly were exemplified in them the grandeur and effect of simplicity in architecture! The Temple of Thesus (Temple of Hephaestus)… cannot but arrest the attention of everyone from its appropriate and dignified solemnity of appearance. The temple of Minerva (Parthenon)… strikes one in the same way with its grandeur and majesty … they will serve as a memorandum to me of what I think should always be a model.”

The beauty of the Greek architectural form is that it was cosmopolitan and held in common. For Blanshard, “a republic of letters became a republic of columns”.

The Greeks ruled the air with their language and realised that people needed space. An elegant example is a black figure pottery Hydria or water jar(c. 510BCE) that was recently on exhibition in the National Gallery in Canberra and which showed women at a fountain house, perhaps in conversation while they collect water. The Greek letters occupying the spaces between the water bearers on the jar speak for themselves.

The second speaker was the noted architect and former Sydney City Councillor, Philip Thalis, Professor of Practice in Architecture NSW, who spoke on the physical reality of Sydney.

Professor Thalis started by quoting from Sir Kenneth Clark in Civilisation:

“If I had to say which was telling the truth about society, a speech by a Minister of Housing or the actual buildings put up in his time, I should believe the buildings.”

Thalis observed that Athens in the late 18th century was waiting for liberation as it was an Ottoman camp and a bucolic scene and drew parallels between Athens and early Colonial Sydney.

He commented that the Darlinghurst courthouse (circa 1840) in Taylor Square Sydney designed by the Colonial Architect Mortimer Lewis, is “the best neoclassical building in Australia” and a supreme example of the Greek Revival architecture in Australia. According to the NSW Heritage Office, the Darlinghurst Court House is a large prostyle temple form with a symmetrical façade, Greek Doric columns and neo-classical pediment. This Greek revival style public building communicates its civic presence through its form, including a fluted stone Doric columned portico supporting a pedimented gable entrance to the central court, flanked by colonnaded wings which stand forward of the robust front elevations.

According to Professor Thalis, the Art Gallery of NSW’s portico is the most beautiful porch on Sydney using indigenous sandstone materials

Other local examples include the Newcastle Town Hall with classical elements imported from Greece via Edinburgh on Scotland (reputed to be the “Athens of the North”).

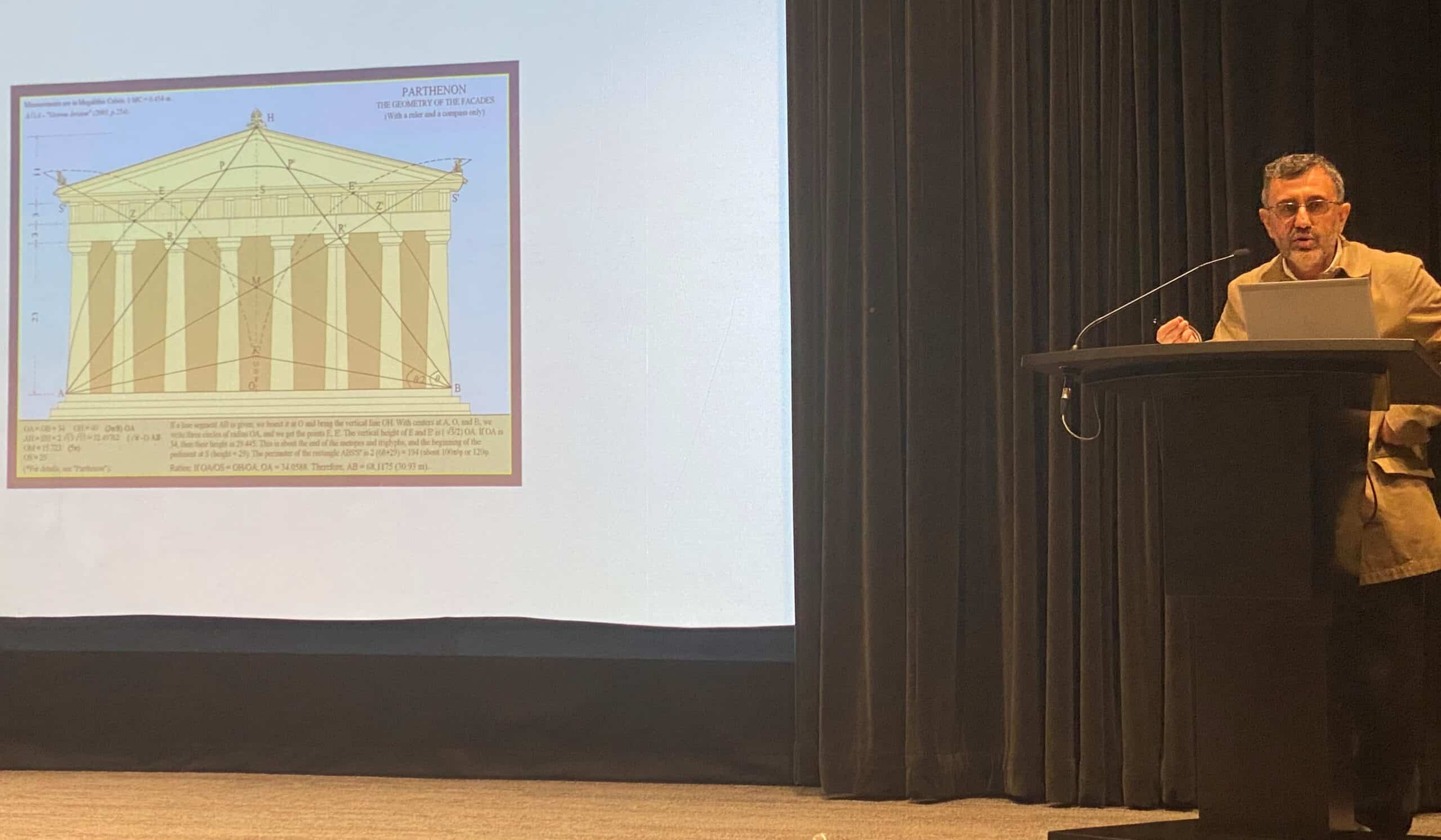

The National Library of Australia in Canberra (1968) has been described as ‘Contemporary Classical’ (‘Late-Twentieth Century Stripped Classical’) in style and its columns were heavily influenced by the Parthenon. As Professor Thalis lamented, in a not uncommon example where cost-cutting undermines architectural integrity and aesthetic sensibility, the building was planned to have the same amount of columns (17 x 8) as the Parthenon but the National Capital Development Commission cut out one row of columns (to 16 x 8) to save money.

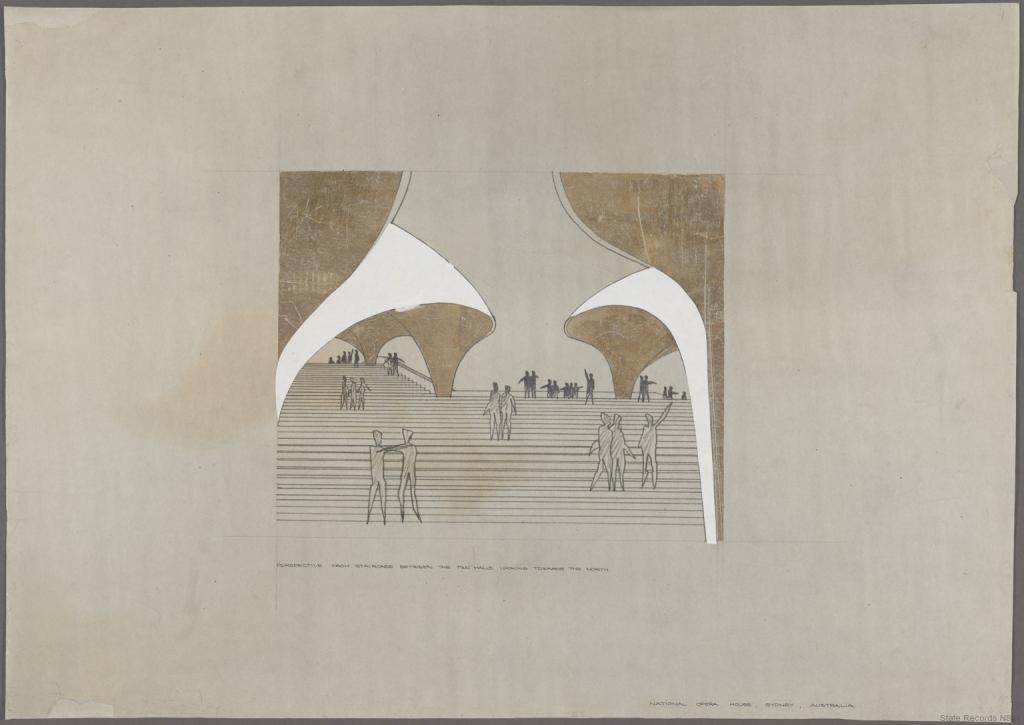

The Sydney Opera House by Jørn Utzon, one of the world’s most iconic pieces of modern architecture, also borrows from Classical Greek ideas. There is a certain Doric sensibility and structural order in Utzon’s work and as with the Parthenon we marvel as we approach the Opera House.

As Philip Thalis concluded, all of history looks to the Parthenon.

The seminar ended on a high note with a stirring presentation by the noted Sydney architect, Angelo Candalepas, who also headed the team which recently won the design competition for the new National Gallery of Victoria Contemporary Gallery in Melbourne.

Invoking the words of the great poet TS Eliot, Candalepas recounted his passion for the ancients. Eliot wrote of the concept of tradition and individual talent being interwoven. Tradition is the gift of the historic sense, and an architect should not only be aware of his place in the present but also how he views architecture from the past and how those works are able to be relevant today.

Invoking the words of the great poet TS Eliot, Candalepas recounted his passion for the ancients. Eliot wrote of the concept of tradition and individual talent being interwoven. Tradition is the gift of the historic sense, and an architect should not only be aware of his place in the present but also how he views architecture from the past and how those works are able to be relevant today.

After all, architecture is a Greek work meaning a high order of building and it essential therefore that buildings contain real architectural elements.

For Candalepas, the Opera House, the Commonwealth Bank building in Martin Place and the modern Governor Philip Tower are his favourite buildings in Sydney and they each owe a debt to Greek ideas and architectural forms and could not have been conceived without a proper understanding of Pythagoras, Euclid and Plato.

The Greek ideal stressed an understanding of civic worth. A human approach to buildings. Pure perfection and a geometric basis for defining beauty from nature. One must be innovative and yet look to the past for, as Candalepas observed, “the Parthenon was not of its own time”.

Structure and decoration are required to give balanced joy to the eye of the observer. Form and space is fundamental to any great work to ensure that buildings emerge from the landscape. Beautiful forms and exact proportions.

And lastly, buildings can be expensive because they leave a legacy. An architect should contemplate how works will be viewed hundreds of years from now, just as we view architecture from the past.

No expense is spared. Pericles – who oversaw the Athenian building program in the 5th century BC – famously said “I will not spare a cent to demonstrate the worth of a society” but ironically he is best known for his funerary oration and not the feverish building activity that was to become the outward expression of the inner wealth and ambition of Athenian democracy.

And the result was the Parthenon, not “wastelands of rubbish” that are served up today in our cities.

For Angelo Candalepas, you want to cry out at the Parthenon because it is talking to you. The Greeks sought perfection because they wanted good work. The metopes and frieze of the sculptural decoration on the Parthenon were the mirror of their society as well as arresting to the eye and giving delight.

The Sydney-based architect pretty much summed up the mood of the room when he declared:

“Being Greek is about being human. Looking at things that make you weak at the knees. Knowing how the eye plays is the work of an architect. It is our poetry. And I still see the Parthenon as though it was built today.”

And as Edward Hollis in The Secret Lives of Buildings has written, the Parthenon is the architect’s dream. It is perfect. It is what architecture was, is and should be.

Fast forward to today, the Opera House stands out, recalling the famous Greek architect and planner Constantinos Doxiadis’ principles of movement and spaces between buildings. Despite not forming part of any formal study or training course at architecture schools in Sydney, Utzon’s Opera House is a singular work of greatness. It is unveiled to you as you approach. As with the Parthenon, it looks out optimistically. The geometry is simple and belies the architect’s unspoken respect for Classical Greece.

Courtesy of the Ancient Greeks the Parthenon represents the whole of humanity in its integration of architecture and sculpture and democratic sublimity.

The legacy of Classical Greece on architecture and western culture is eternal.

George Vardas is Arts & Culture Editor and also co-founder of the Acropolis Research Group