That we've broken their statues,

that we've driven them out of their temples,

doesn't mean at all that the gods are dead.- IONIAN, Constantine Cavafy

MOTIVE MATTERS

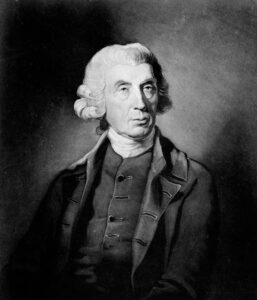

“The plans for my house in Scotland should be known to you… The Hall is intended to be adorned with columns… If each column were different…I should think the effect would be admirable, but perhaps better if there were two of each kind. In either case I should wish to collect as much marble as possible. I have other places in my house which need it… You do not need any prompting from me to know the value that is attached to a sculptured marble or historic piece.”

- From Lord Elgin’s letter in 1801 to Giovanni Battista Lusieri, the overseer of his collecting operations in Athens.

Ask any District Attorney or State Prosecutor which version of a perpetrator’s motives are closer to the truth, and without hesitation they will say “The subject’s own spontaneous declarations before, during and just after the act in question – as opposed to the narration crafted long afterwards by parties interested in a more favourable interpretation.” And while there are sheaves of correspondence similar to the excerpt above, and numerous letters back and forth between Elgin and his team detailing the bribes and expensive gifts given to the Disdar (Commander of the Acropolis citadel), a senior judge and other Ottoman officials in Athens, there is not a single line of correspondence during the time of his Ambassadorship demonstrating a desire to preserve these priceless sculptures for posterity, to introduce a taste for classical antiquity in Scotland or to elevate the arts in England. That all came later.

In the meantime, Elgin and “his marbles” spent a harrowing few years making their way back to Britain. When the 140 crates of sculptures arrived, shipment by shipment, they were stored in various lodgings in London, including a musty shed. And when his Lordship himself arrived home following his three years’ detention as Bonaparte’s prisoner of war, his own situation was little better than that of his collection. Now completely noseless, deep in debt and without diplomatic posting or peerage, Elgin suffered the additional humiliation of seeing his marriage fall scandalously and publicly apart. Not all the sculptures in Greece, it seems, could retain or regain his wife’s affection, and her affair with Robert Ferguson (co-defendant in Elgin’s lawsuit) hit the courts and the newspapers with much fanfare in the year 1808. A small sample of testimony from the trial (by William Richard Hamilton, Undersecretary in the Foreign Office and Elgin’s private secretary in Constantinople) gives one a sense of the sensation it must have caused, sealing Elgin’s reputation as a cuckold rather than connoisseur of antiquities.

- Mr. Hamilton, would you say that this withdrawal [of affection] on the part of Lady Elgin was due to a definite reason?

-- Yes. While in Constantinople, Lord Elgin contracted a severe ague which consequently resulted in the loss of his nose.

- Mr. Hamilton, would you say that her Ladyship’s interest in Lord Elgin began to wane at this point?

-- Yes.

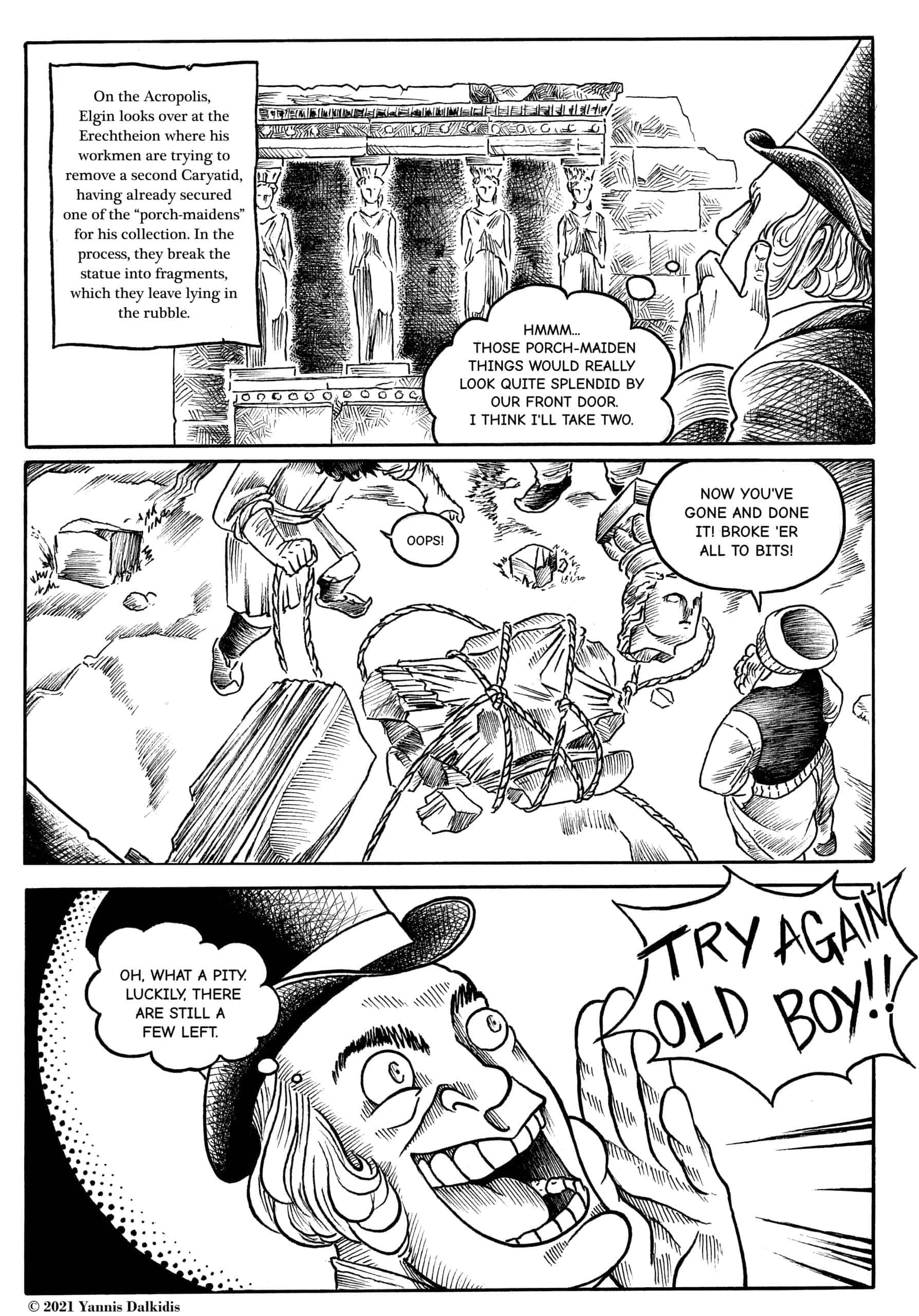

At this time, decorating Broomhall disappeared from Elgin’s correspondence and agenda, and he turned his attention to collecting money instead. Estimating the expenses incurred procuring and shipping “his marbles” at over £74,000, Elgin wrote to Prime Minister Lord Liverpool that: “The whole proceeds of my patrimonial estate, my dowry, and every private fund at my disposal have been entirely absorbed,” and yet he still owed more than half that amount to creditors in England. Signing over the marbles themselves as surety against these debts, he began searching in vain for a buyer but soon realized that the sum (£74,000) was far beyond the means of even the most avid private connoisseur or antiquarian. The only solution was the public purse. However, since Government funding for the arts in Britain was in more or less the same dismal state as it is today, Elgin began to weave a different kind of narrative about his collection and his motives. In this new version of Elgin’s tale, he only decided to intervene and physically remove the sculptures from the Parthenon and other temples after he witnessed the “mischievous Turks” abusing them, using them for target practice, pounding them into powder for mortar, or selling them off to travelers as souvenirs. But remember this: his men began dismantling the Parthenon to remove the sculptures in July of 1801 (see eyewitness accounts and painting by Edward Dodwell from the previous column), while Elgin himself first set foot in Athens a full year later – in 1802, after much of the sculpture and many architectural elements had already been removed. In his later telling of the story, Elgin was motivated solely by aesthetic and patriotic interests to preserve and protect these priceless symbols of the Golden Age of Pericles – in language that conveniently reinforced Britain’s own self-concept of empire – and so he selflessly took it upon himself, at enormous personal expense, to rescue them from the “barbarous Mohammedans”.

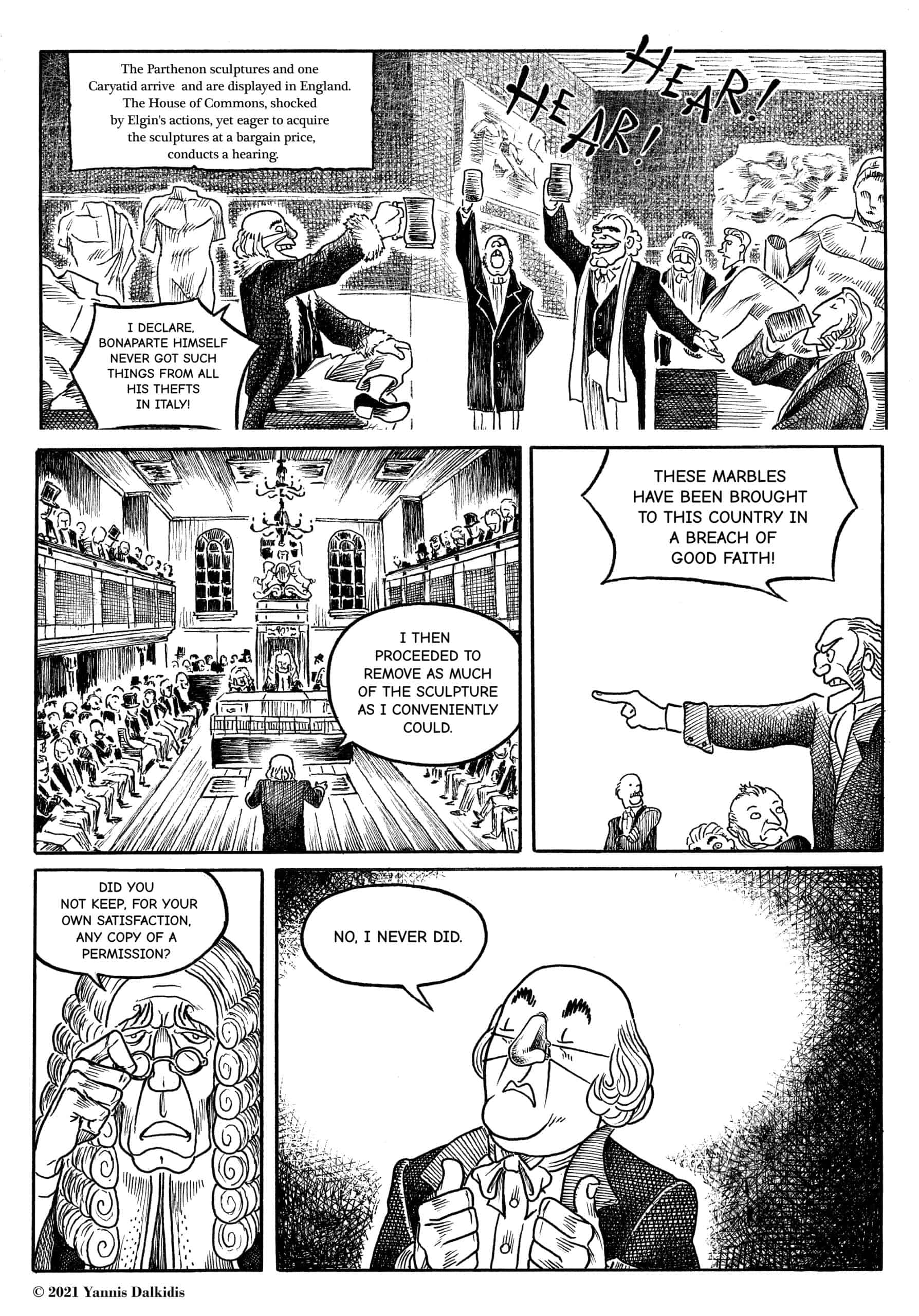

Presented with this dilemma/opportunity, the British House of Commons in 1816 convened a Select Committee to examine whether or not this collection of sculptures was worth acquiring and, if so, whether they could be had for a bargain and in such a way that further rogue operations of this kind might be discouraged. The Marbles were now in Britain, and there was no question of returning them to Greece and the now thoroughly ruined Parthenon. It was as dramatic a fait accompli as one could possibly imagine. Most of the members recognized that Elgin had abused his position as Ambassador of His Majesty’s Government in order to procure the sculptures, and they were almost unanimous in their opinion that he had acted outside acceptable legal and ethical norms. During the course of the hearing, they further realized, from Elgin’s own testimony and that of the Reverend Hunt, that he had also misrepresented his intentions when applying for permission for his five artists to access the Acropolis and “draw, take measurements and make plaster casts of the sculptures”. One of several letters from the Acting Grand Vizier in Constantinople echoed this misrepresentation by declaring that Elgin’s intentions were acceptable “as there would be no harm” from these activities “to the walls or edifices themselves”. As we shall see next week, Ottoman law was actually very strict when it came to protecting historic or religious sites and monuments. What happened in Athens was something quite different.

In order to acquire these priceless antiquities, however, the Committee decided to overlook Elgin’s misrepresentations, his abuse of office, the extensive bribery and lack of documentary evidence showing either purchase or explicit permission. Testimony as to the dismay caused by Elgin’s activities included this statement by Parliament’s own MP John Morritt, who described his visit to Athens in 1795, seven years prior to Elgin’s first visit: “They (the Marbles) were looked on as the property of the state, and the Turkish soldiers interfered to stop anyone from approaching them. The Greek populace was decidedly and strongly desirous that they should not be removed.” Even the Committee’s leading attorney, MP Sergeant Best, vehemently protested that: “These Marbles have been brought to this country in breach of good faith!” The Committee, however, voted to purchase the Sculptures - and to accept the patriotic version of Elgin’s motives and actions as their basis for doing so. This version of events became part of the origin story of the Parthenon Marbles and their journey to the British Museum, where they were transferred by an Act of Parliament in 1816. You see, in the words of the Museum’s Director Hartwig Fischer, which were then echoed by Prime Minister Boris Johnson earlier this year, “It was all perfectly legal.”

Neither Purchased nor Permitted

Much has been made of the supposed firman obtained by Elgin, but experts on such documents and on the extensive Ottoman archives in Constantinople have testified recently that no such document was ever issued. In order to remove elements of a shrine or historic monument such as the Parthenon, a firman would indeed be required. An authentic firman of this type and for this purpose, however, could only be issued and signed by the Sultan himself, and each firman was copied and recorded in a special volume in the royal archives. We will explore the role of firmans in Islamic law next week, but suffice it to say that no such permission was ever issued giving Elgin’s people the right to harm the temples on the Acropolis or remove sculptures from their walls. Nor did Elgin purchase these sculptures. Following talks with the Sublime Porte in 1812, Elgin’s successor in Constantinople, Ambassador Robert Adair, disputed any claims of legal purchase as well.

Extract from letter to Elgin from Robert Adair, his successor

as Britain’s Ambassador to the Sublime Porte:“My Lord, In answer to your Lordship’s enquiry respecting the marbles collected by your Lordship at Athens… I have to inform your Lordship that Mr. Pisani more than once assured me that the Porte absolutely denied your having any property in those marbles. By this expression I understood the Porte to mean that the persons who had sold the marbles to your Lordship had no right so to dispose of them… I have the honour to be, your Lordship’s most obed(ient) and humble serv(an)t."

- R. Adair

The Select Committee of 1816 largely concurred that Elgin’s actions amounted to an abuse of his diplomatic position, were in breach of good faith, occurred without the consent of either Greeks or Turks in Athens – and only succeeded by dint of extensive, prolonged bribery and threats. Nevertheless, voting to make the best of a bad bargain, the Committee decided to purchase the marbles for a sum (£35,000) that was less than half of what Elgin requested to cover his debts and expenses and to give them to the British Museum - complete with the new patriotic narrative about the motives and circumstances surrounding their acquisition. This major outlay of public funds was justified as a great boon to the arts and education in Britain, while Lord Elgin was characterized as their patron saint.

Back home in Vermont this would be called “putting lipstick on a pig”.

Lord Elgin’s legacy and “Elginism"*

Some things run in families: sneezing three times instead of twice, a penchant for big cars and small dogs, a green thumb, prominent ears or a sweet tooth. The Elgin family, however, had a fondness for the cultural heritage of other nations. Elgin’s son James, the 8th Earl of Elgin, was one of the British Empire’s most powerful and successful diplomats of the time.

As High Commissioner of China in 1860, in order to persuade the Chinese to keep their markets open to the opium trade run by The East India Company, James continues a family tradition. He orders 4,000 soldiers to encircle the Summer Palace outside of Beijing and then commands them to make of it an example. It takes these troops a full three days to entirely torch and strip the magnificent 800-acre Palace complex, burning alive the 300 servants and staff trapped inside and removing thousands of historic antiques. Like father, like son.

*(Elginism: an act of cultural vandalism)

NEXT WEEK: We will look into the question of legality, according to Islamic law in the Ottoman Empire during Elgin’s time, in Britain itself at the beginning of the 19th Century and today, all around the world.

ABOUT THE PARTHENON REPORT | DON MORGAN NIELSEN:

In this bicentennial year since the birth of the modern Greek State, of both pandemic and celebration, Greek City Times is proud to introduce readers to a weekly column by Don Morgan Nielsen to discuss developments in the context of history, politics and culture concerning the 200-year-old effort to bring the Parthenon Sculptures back to Athens.

Classicist, Olympian and strategic advisor, Don Morgan Nielsen is currently working with an international team of colleagues to support Greece’s efforts to repatriate the Parthenon Sculptures.

Click here to read ALL EDITIONS of The Parthenon Report by Don Morgan Nielsen

Feature Image : Copyright Nick Bourdaniotis | Bourdo Photography