That we've broken their statues,

that we've driven them out of their temples,

doesn't mean at all that the gods are dead.- IONIAN, Constantine Cavafy

THE END OF ELGIN'S NOSE

The story of the Parthenon is really the story of Pericles, Phidias, Francesco Morosini and Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin and Kincardine (a.k.a. “Lord Elgin”). In a tale equally divided between creation and destruction, these are the four main protagonists, whose fame or infamy is inextricably tied to this most famous of buildings*.

LORD ELGIN - COMPLEXITY & CONTRADICTION

When coming to Lord Elgin however, and hoping through him to move our discussion into the modern era, I suddenly became mired in the complexity of his character, the contradictions in his motives and the messiness of his personal life. The more I struggled to dispatch Lord Elgin with a quick summary of his deeds and misdeeds, the more I ended up with my leash wrapped around a tree, unable to move forward. At first, I thought that he might serve as a symbol of Britain’s imperial arrogance and ambition, but so much of what he did failed to make sense in that context. Then, several weeks ago, I asked a former student to go to the Scottish Records Office in Edinburgh to try to find court transcripts, newspaper accounts or other public records dealing with the sensational trial of 1808 in which Elgin sued his wife Mary for divorce on the grounds of adultery – suing as well Robert Ferguson of Raith as co-defendant for the extraordinary sum (at that time) of 20,000 pounds sterling. Reading some of the testimony from that trial and later coverage in The Times, one gets the sense of a man as broken as the sculptures he gathered in Greece, disfigured by a terrible disease, desperate, humiliated and hounded by creditors – quite different from his portrait from 1788 by Anton Graff, which shows a dashing young officer and nobleman at the beginning of what everyone assumes will be a glorious career.

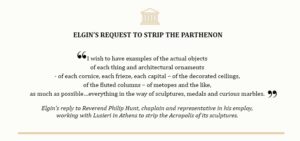

Just ten years later, Elgin obtained the post of British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and a year following that, in 1799, he married Mary Hamilton Nisbet from one of the wealthiest land-owning families in Scotland. As befitting a socially and professionally ambitious young Lord, Elgin hired one of the country’s most distinguished architects, Thomas Harrison, to redesign and enlarge the family seat, Broomhall, in County Fife. Harrison convinced Elgin to turn Broomhall into a model for the newly popular Greek Revival movement, assuring him that such a project would result in the “grandest house in Scotland”. While the annual income from the Broomhall estate and its various tenant-farmers was only £2,000 annually – and therefore not nearly enough to support the kind of life Elgin envisioned, Mary Nisbet’s dowry was considerable, and her family gave the young couple other substantial loans to help them get started. As Elgin began preparing to leave for Constantinople, he and Harrison had several conversations regarding the opportunities afforded by his posting – which included the occupied lands of Greece, in particular Athens and its Acropolis, upon which the Greek Revival Style was based. Perhaps, en route to Constantinople, Harrison suggested, Elgin might stop in Italy to hire some artists who could then sketch and take mouldings of the antiquities as decoration for the reception rooms and hallways of Broomhall. It probably did not occur to either man at that point to actually dismantle the original prototype for the Greek Revival Movement – the Parthenon itself – and strip it of its sculptural decoration in order to decorate his Lordship’s own Greek Revival mansion in northern Scotland.

Until obtaining his position as Ambassador, as far as can be gleaned from Elgin’s fairly extensive correspondence over the years, neither Greece nor her antiquities had even remotely figured among his passions. He belonged to no society of dilettantes or enthusiasts of the ancient world, never expressed an interest in Greek (or British) art and culture, and didn’t even have a bust of Pericles on his desk. In fact, Lord Elgin only appeared to discover the glories of Athens when looking to burnish his cultural credentials, please his new wife and decorate their home.

In September of 1799, Lord and Lady Elgin set sail for Constantinople. Although the British were not in great favour in Constantinople at that time, British forces in Egypt drove Napoleon’s army from that country in 1801 and restored Turkish dominion there. From that point forward, relations between Britain and The Sublime Porte in Constantinople [Sultan Selim III, his court and key government officials] became ever warmer, and the new British Ambassador in Constantinople was suddenly a very popular man, able to command great personal and political favours. And so, in keeping with his plans for turning Broomhall into “the grandest house in Scotland” he instructed a young chaplain in his employ, the Reverend Philip Hunt, to draft a letter to a friendly official in the Ottoman Government requesting permission for his artists in Athens to have unhindered access to the Acropolis and to erect scaffolding around the temples so that they might draw, measure and make plaster casts of the sculptures. Hunt was well aware that a decade earlier the French Ambassador had requested – and received - permission (over strenuous objections by the British Ambassador of the time) to do the same thing, that is: draw and make plaster casts of the sculptures on the Acropolis. Hunt was also aware that the French request to remove a metope from the Parthenon in 1790 had been quickly and firmly rejected by this same Sultan and his far less malleable Grand Vizier, now luckily away in Egypt. Taking his cue from this precedent, the permissions sought by Elgin were of a very non-invasive sort. And when a letter of reply presently arrived from the Acting Grand Vizier in Constantinople, characterized as a firman by Elgin and his retinue, Hunt improvised and enlarged upon its provisions through a steady supply of money and gifts for the Turkish officials in Athens, including: suits of fine European clothing, chandeliers, firearms, jewellery, horses, telescopes, and countless rolls of silk and damask. This largesse was sharpened by threats of sending the Commander of the Acropolis citadel (the Disdar) and his son into slavery, exile or death if they failed to comply with Elgin’s wishes.

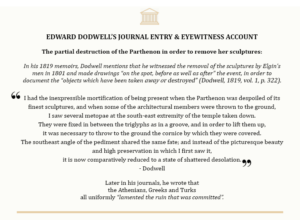

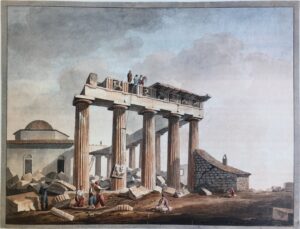

Hunt soon began to test the limits of their freedom on the Acropolis by requesting permission from the Ottoman Governor of Athens (the Voivode) and the Disdar to remove the best of the metopes from the temple. Permission was grudgingly given, and Lusieri prepared his scaffolding and workmen to begin dismantling the Parthenon. This watercolour by Edward Dodwell, who was present in Athens at the time, illustrates the removal of the first metope, while his travelogues, written in 1819, contain his impressions which he had recorded at the time in his journals.

Another traveller present at the scene, Edward Daniel Clarke, described the same scene, but also included the private misgivings of Lusieri and the demonstrable regret of the Disdar.

As one can see from these eyewitness accounts, the collection of the sculptures from the Acropolis was a brutally destructive act, intentionally whitewashed in subsequent years by the language used to describe it. “Removing” or “taking down” the sculptures from the temple brings to mind taking a picture down from a wall, perhaps for a gentle dusting, when in fact Elgin’s men had to destroy the wall itself, and in some cases the sculptures, in order to “remove” them.

No Turk, in the entire history of the Parthenon, had ever inflicted even a tiny fraction of the damage done to the monument by the 5th Century Christian iconoclasts, by Francesco Morosini and his bombardment – or by the British Ambassador Lord Elgin seeking to furnish his family estate in Scotland. If Elgin had indeed been motivated by a concern for preserving and safeguarding the finest specimens of classical antiquity, for far less than the fortune he spent dismantling the temple to obtain its sculptures, he might have prevailed upon the Ottoman officials, as Edward Daniel Clarke and Lusieri sorrowfully acknowledged: “to see an order enforced to preserve rather than destroy such a glorious edifice.”

Image: Edward Dodwell and Simone Pomardi, Removing the marbles at the south-east corner of the Parthenon, 1801-1805, watercolour, The Packard Humanities Institute, Los Angeles.

THE SCENE OF THE CRIME

But while all this was happening in Athens, back in Constantinople Ambassador Extraordinary Lord Elgin began to show the symptoms of a dreadful disease, thought by many to be a kind of syphilis whose principal manifestation was the gradual disintegration of the nose. As the disease slowly worsened, the Elgin's travelled to Athens for the very first time – to observe the collecting operations of Lusieri and dozens of workmen, who toiled day in and day out, hacking, prying and sawing to remove sculptures and architectural elements from the temples of the Acropolis. 100 crates full of metopes, blocks of the frieze, a caryatid from the Erechtheion and other antiquities soon crowded one of the quays in the Port of Piraeus, and Elgin wrote letter after letter to Government officials in Britain complaining of his vast expenses, begging for their support, dropping hints about a life peerage and even requesting a navy frigate to escort his treasures back home. Increasingly comparing himself to Napoleon and his wholesale looting of Italy’s cultural heritage, Elgin took to boasting that: “Bonaparte himself has not got such a thing from all his thefts in Italy.”

In 1803, now completely noseless and deeply in debt, Elgin’s career as a diplomat was over. His wife had gone home to take up with an attractive neighbor, Robert Ferguson. A boatload of antiquities from the Acropolis lay at the bottom of the sea off the Greek island of Kythera, while the final shipment of “his marbles” wouldn’t reach home until 1812. Travelling first to Italy and then alone through France, Elgin was detained as a prisoner of war for three long years, during which time he wrote with increasing desperation to Lusieri back in Athens, urging him to redouble his efforts to gather every possible scrap of sculpture from the Parthenon and other temples and to ship them, by whatever means possible, to England. Little did it seem to matter that his original plan to decorate Broomhall had taken on the dimensions of an obsession and a life of its own, with no apparent plan for what he might actually do with “his marbles” and no more money to do it with. His inheritance, dowry and massive loans had long been exhausted by the £74,000 spent in bribes and spiralling expenses to “strip and ship” his treasures to England, while his letters to two Prime Ministers over several years begging for a life peerage went unanswered. Nevertheless, a new plan unfolds. Elgin stops in Naples to ask the famous neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova his advice on restoring the badly damaged and often noseless sculptures. Canova was horrified at the idea and sent him on his way – on to 3 years’ detention in France as Bonaparte’s prisoner of war.

So, we come to the end of Elgin’s nose and the beginning of his ending - which unfolds with a sensational divorce trial in Scotland in 1808 and a contentious hearing in Parliament in 1816. A curious transformation in his rationale for removing the sculptures from the Parthenon also begins to emerge at this time, a transformation which may partly explain why the Parthenon Sculptures are held today in Bloomsbury rather than Broomhall.

“Noseless himself, he brings home noseless blocks,

To show what time can do and what the pox.”

- Lord Byron

*NOTE & ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

There is also a little-known chapter of destruction during the 5th Century CE, when Christian iconoclasts destroyed many of the Parthenon’s “pagan” sculptures – primarily the metopes – in the process of converting Athena’s temple to the Church of Ayia Sophia. For more on this sorry episode, I highly recommend the fabulously informed and compendious web-site: Elginism This website is curated by Matthew Taylor, one of the most insightful and dogged detectives involved in the efforts to find a solution to the “Elgin problem”. Taylor and his fellow founders of The Acropolis Research Group have probably done more than any other group (or Greek Minister) to put the cause of repatriation on firm, reasonable and well-researched footing and have contributed immensely toward our understanding of the arguments and issues involved.

NEXT WEEK: We continue with Part 2 of the Elgin saga.

ABOUT THE PARTHENON REPORT | DON MORGAN NIELSEN:

In this bicentennial year since the birth of the modern Greek State, of both pandemic and celebration, Greek City Times is proud to introduce readers to a weekly column by Don Morgan Nielsen to discuss developments in the context of history, politics and culture concerning the 200-year-old effort to bring the Parthenon Sculptures back to Athens.

Classicist, Olympian and strategic advisor, Don Morgan Nielsen is currently working with an international team of colleagues to support Greece’s efforts to repatriate the Parthenon Sculptures.

Click here to read ALL EDITIONS of The Parthenon Report by Don Morgan Nielsen

Feature Image : Copyright Nick Bourdaniotis | Bourdo Photography