The Greek Government has declared that 2024 is dedicated to Lord Byron, the famous Romantic poet, who died in 1824 during the Greek War of Independence.

On the 200th anniversary of Lord Byron’s death the Greek Festival of Sydney in collaboration with the Consulate General of Greece in Sydney presented a lecture at NSW Parliament House on 18 April 2024 to honour the great Philhellene and to explore how Byron came to be considered a “Greek poet” during Greece’s greatest hour of need, and how his writings and interventions would help influence the eventual outcome of the revolution.

The Greek Consul-General, Ioannis Mallikourtis, opened the proceedings with a sweeping historical analysis of the post-Napoleonic era and in particular the geopolitical and diplomatic state of play at the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in March 1821. The Holy Alliance of the Great Powers (Britain, France and Russia), which wanted to maintain the existing balance of power following the Congress of Vienna, were openly hostile to what they initially viewed as an insurgency against the degenerating Ottoman Empire.

However, leading figures in the revolution, particularly amongst the educated Greek elite of the diaspora, such as Adamantios Korais and Alexander Mavrocordatos, realised that the Greek Revolution had to ‘fit in’ with the existing balance of power in Europe without shaking its foundations.

Lord Byron essentially internationalised the Greek Revolution whilst ensuring that a new independent Greek State was anchored to the West.

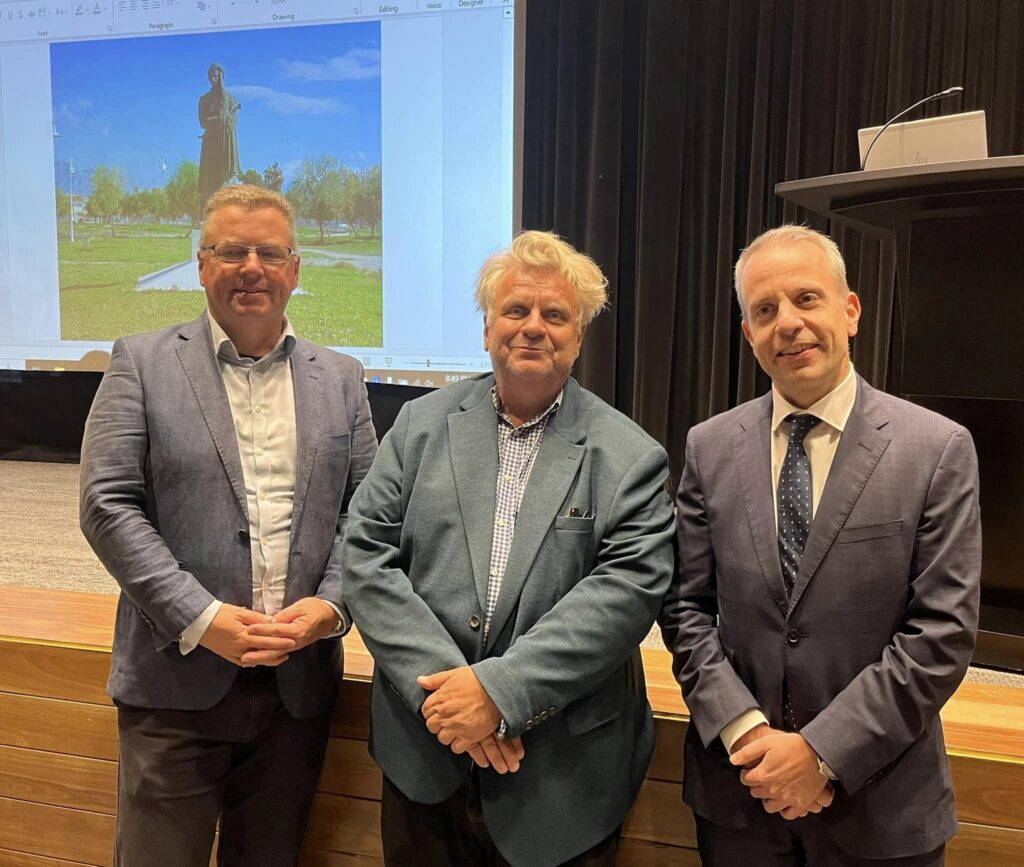

(L-R): Professor Mark Byron, Professor Vrasidas Karalis and Greek Consul-General, Ioannis Mallikourtis (credit: Consulate General in Sydney)[/caption]

(L-R): Professor Mark Byron, Professor Vrasidas Karalis and Greek Consul-General, Ioannis Mallikourtis (credit: Consulate General in Sydney)[/caption]

As Mr Mallikourtis explained, Lord Byron was acutely aware of what was at stake even before he crossed from Italy to Cephalonia, a British protectorate at the time, in the summer of 1823. The aristocratic rebel understood that the Greeks would have to prove that they were capable of governing themselves and also convince the Great Powers that their own geopolitical interests would be better served by supporting the Greek nation rather than by maintaining the status quo in the face of a declining empire.

Lord Byron truly believed that the Greek Revolution would be a turning point for the rest of Europe:

“I cannot calculate to what height Greece may rise. Hitherto it has been a subject for the hymns and elegies of fanatics and enthusiasts; but now it will draw the attention of the politician.”

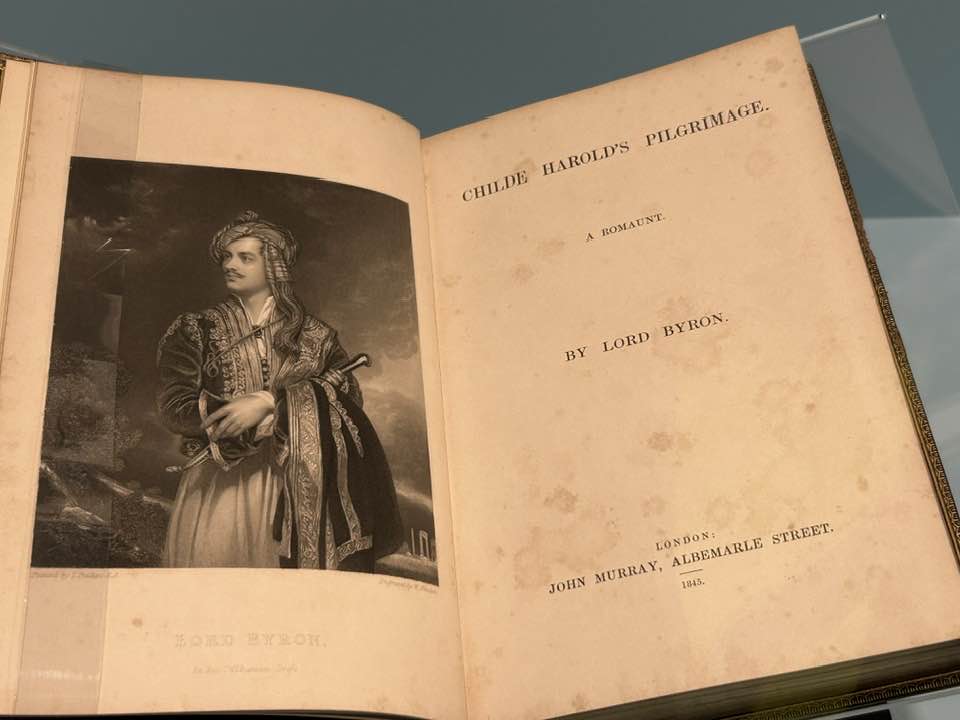

According to the Consul General, this is what is so fascinating with Lord Byron. The impression many have is that that he was solely a romantic poet or even a utopian. We refer to the Byronic heroes born out of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage yet in real life, and despite his posturing and flamboyant demeanour, Byron had sound geopolitical and pragmatic judgement, assisting the Greek cause both financially and organisationally. He also had a very critical eye on the bickering between the Greeks, sparing no effort from Missolonghi where he was based to unite them and prevent them from self-destruction through civil strife.

Lord Byron was devoted to the cause until the end and it was through his death that his geopolitical vision would materialize. His death in Missolonghi on 19 April 1824 was a sensation across Europe, reviving the waning international public interest in the Greek cause and ensuring thereafter that the Greek Revolution would remain a constant European concern.

The next speaker, the Hon Mark Buttigeig MLC, the NSW Parliamentary Secretary for Multiculturalism, standing in for a temporarily indisposed Minister Steve Kamper, praised Byron’s Philhellenism and his conviction to travel to Greece to join its proud people in the resistance and to help raise awareness in this noble cause.

Lord Byron and Greece: The “Greek” poet and his nation

The first of the guest speakers was Professor Mark Byron BA, MPhil, PhD (Cambridge) Discipline of English and Writing, University of Sydney, who spoke on some of the more poetical aspects of Lord Byron’s career particularly as they pertain to Greece.

But at the outset he sought to address an obvious question: was he in fact related to the famous Romantic poet? Mark Byron is not sure but he does attribute his interest in the exploits of Lord Byron to what he termed “nominative determinism”, the idea that people are psychologically predisposed to pursue interests that evoke their names in some way.

As to why Byron can be considered a Greek poet, Professor Byron recalled Lord Byron’s own musings: “If I am a poet the air of Greece made me one”

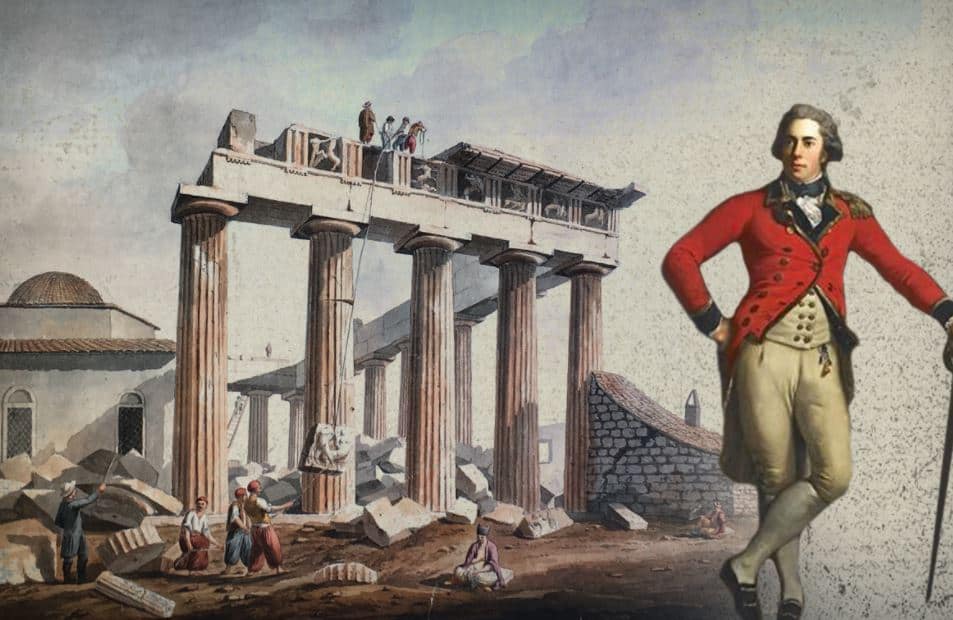

Lord Byron’s first trip to Greece in 1809 was on the so-called Grand Tour when he travelled with his friend John Cam Hobhouse as they ventured through Albania, Greece and Turkey. There was moderately little knowledge about Greece at the time but Byron’s travels were part of the new wave of interest in Greek architecture, culture and learning, that attracted well to do young men seeking to enhance their worldliness and sophistication.

As Professor Byron pointed out, this was also at a time of growing adulation of Classical Greece as the birthplace of European civilisation, as reflected in what one of Byron’s friends, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, famously wrote in the preface to his iconic verse poem Hellas (ironically published to help raise funds for the Greek War of Independence):

“We are all Greeks. Our laws, our literature, our religion, our arts have their root in Greece. But for Greece, Rome, the instructor, the conqueror, or the metropolis of our ancestors, would have spread no illumination with her arms, and we might still have been savages and idolaters…”

Byron was inspired by the thought of Greeks re-emerging from antiquity as the “world’s great age begins anew” (again to quote Shelley) because of the belief that Hellenic heritage was common to all of western civilisation.

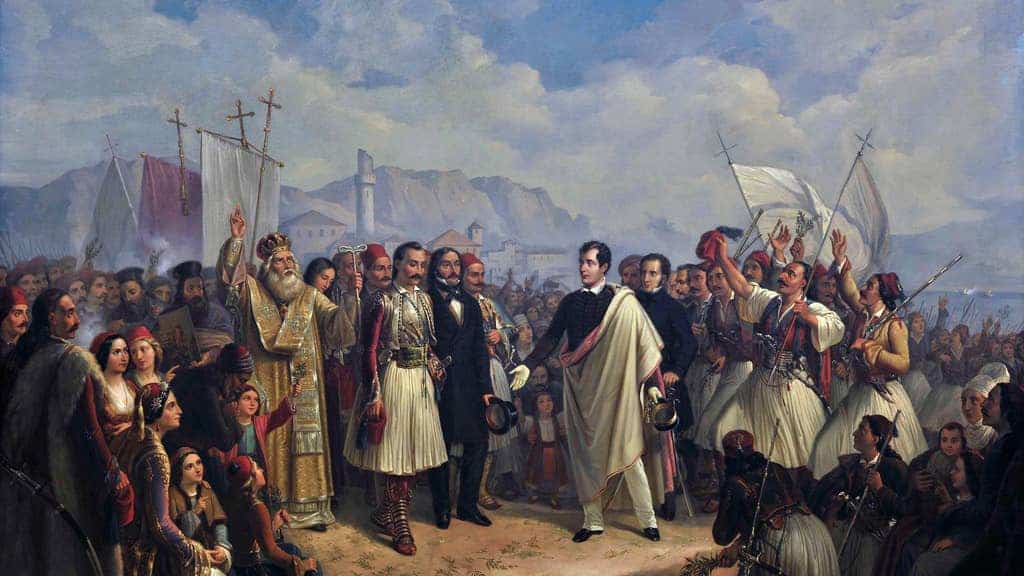

The Oath of Lord Byron on the Grave of Markos Botsaris (painting by Ludovico Lipparini)

The Oath of Lord Byron on the Grave of Markos Botsaris (painting by Ludovico Lipparini)

There was a tendency in Western Europe to look upon the Greeks with some despair. On the contrary, Byron viewed the Greek people far more positively and celebrated the fact that Greeks have been able to produce a scholarly culture despite the sociopolitical constraints they faced. As Professor Byron explained, the Greek presence in Byron’s poetry is often viewed as being steeped in an atmosphere of melancholy relatedness and loss as very much the mode of writing about Greece at the time. But Byron and Hobhouse were more critically interested in the challenges and opportunities open to learning in the modern context for the Greek people.

Byron also defended Greece’s cultural integrity in his very trenchant criticism of Lord Elgin in his famous verse poem, Child Harold’s Pilgrimage, following the forced removal of the Parthenon sculptures to London:

But who, of all the plunderers of yon fane

On high, where Pallas linger'd, loth to flee

The latest relic of her ancient reign;

The last, the worst, dull spoiler, who was he?

Blush, Caledonia! such thy son could be!

England! I joy no child he was of thine:

Thy free-born men should spare what once was free

Yet they could violate each saddening shrine,

And bear these altars o'er the long-reluctant brine.

Lord Elgin was the perpetrator of this cultural sabotage and damage and that was an embarrassment to Byron personally because they were both Scots (the reference to Caledonia in the poem being Scotland). Filled with indignation, his poetry channeled his immense rage against the ignoble depredations of the rapacious Elgin, and that "modern Pict's ignoble boast ... to rive what Goth, and Turk, and Time hath spared".

According to Professor Byron, this gives a clue as to how Lord Byron viewed Greek cultural regeneration when he calls Elgin the modern Pict or Scotsman, showing a baroness of mind to exploit the weak conditions of the Greek people to plunder its ancient remains. Byron calls out the forced displacement of Greece’s monuments by erstwhile allies.

This also inverted the trope that was quite common at the time that the Greeks and Greece embodied a kind of hopelessness. As Lord Byron declared:

Fair Greece! sad relic of departed worth!

Immortal, though no more! though fallen, great!

Who now shall lead thy scatter'd children forth,

And long accustom'd bondage uncreate?

Professor Mark Byron concluded his presentation by reminding the audience that Lord Byron had also inscribed himself in the face of the nation by leaving his permanent mark on the Temple of Poseidon at Sounion.

Or did he?

The inscribed name possibly dates from Byron's first visit to Greece when he spent several months in 1810–11 in Athens, including two documented visits to Sounion. There is, however, no direct evidence that the inscription was made by Lord Byron himself but the romantic notion that he did endures.

As does his legacy.

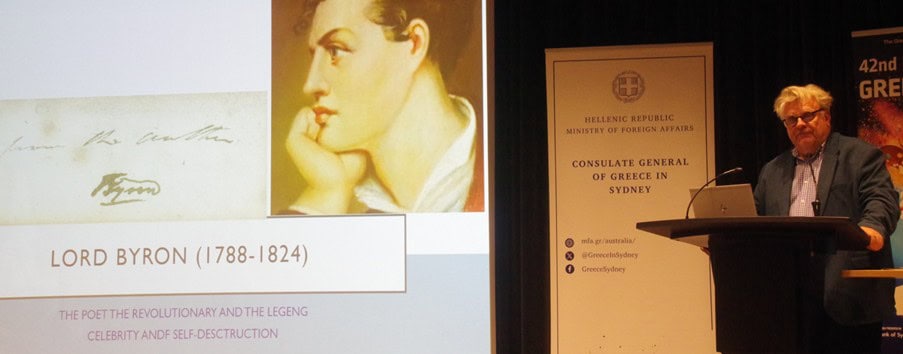

The Poet, the Revolutionary and the Legend: Celebrity and Self-Destruction

Professor Vrasidas Karalis, Sir Nicholas Laurantus Professor of Modern Greek, Chair of Modern Greek Department, University of Sydney then addressed the audience with a masterful overview of Lord Byron’s life and its seeming contradictions, reprising parts of his fascinating 2021 seminar, Lord Byron: The Poet and the Revolutionary in Greece, delivered to the Greek Orthodox Community of Melbourne.

Who was Lord Byron?

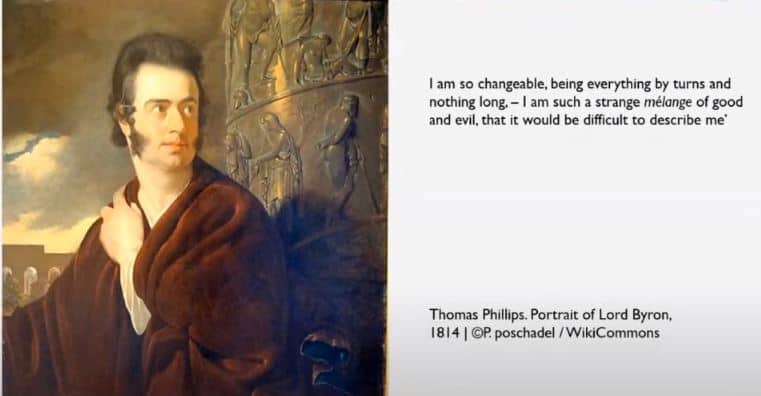

George Gordon Byron, the sixth Lord Byron, was one of the most celebrated poets of the Romantic period as well as a peer, politician and global celebrity, famed not only for his verse but for his controversial lifestyle and active involvement in the Greek War of Independence.

He was born in London in 1788 and his later frenetic energy was inherited from his womanising Navy father, “Mad Jack” Byron, who died by suicide when young George was only three. Although born with a club foot and enduring life-long problems with his weight, the young Byron was physically active, including taking on a renowned pugilist, John “Gentleman” Jackson, in a boxing contest and swimming for miles across the tumultuous waters of the Hellespont.

He travelled extensively across Europe spending time with the famous romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife Mary Shelley and he dedicated his wealth and life to the fight for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire before finally succumbing to illness at the tender age of 36.

According to Dr Karalis, because of the presence of Lord Byron, Greek culture is universal, and not something that is simply a local or provincial reality. It goes to the very heart of the legacy of the Western European tradition, or what may be termed the “Greco-Occidental” tradition.

It is therefore no coincidence that the only non-saint first name given by priests in Greece is the hellenised version of his name, Vyron or Vyronas. And that is why they refer to the sacred memory of Byron because of the reverence for Lord Byron as though he were a prophet, the “Messiah for Freedom”.

The famous painting by Theodoros Vryzakis “Lord Byron at Missolonghi” represents the “idealisation of Byron” in the 19th century but also the elevation of Lord Byron to a cultural and national icon of Greece. People are pictured surrounding Byron like a chorus from a Greek tragedy, looking upon him with reverence and love, with piety, with revolutionary fervour, with anticipation and anxiety.

Byron is a revolutionary and is a legend and a celebrity. According to Dr Karalis, Lord Byron was like a popstar phenomenon, the “Lady Gaga” of the period. To others he was the nineteenth century “bad boy”. The level of “Byromania” or celebrity cult was mind-boggling and the Byronic look was mimicked everywhere in mirrors, in the hope of catching the curl of the upper lip, and the scowl of the brow.

But his influence was profound, as the famous historian Roderick Beaton in “Byron’s War” writes:

“By the summer of 1823 Byron, “mad, bad and dangerous to know”, had single-handedly invented the modern cult of celebrity and was adored and reviled throughout Europe as well as as far away as America as one of the defining spirits of the Romantic movement in poetry and the arts.”

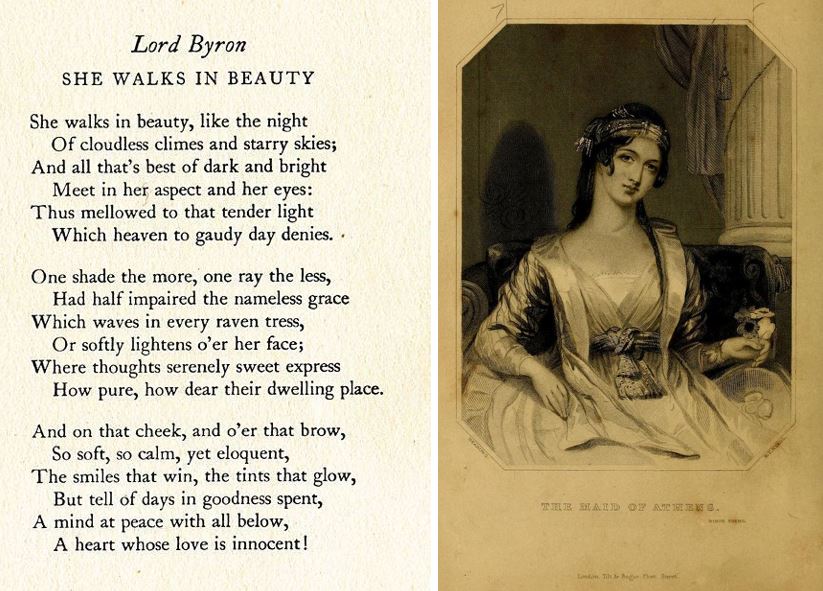

According to Dr Karalis, Byron's best poem is arguably “She Walks in Beauty”.

His poetry became part of the Greek character, as he implicitly acknowledged when he wrote “the spell is broke, the charm is flown” when he first arrived in Greece.

Byron was also one of the first poets to talks about himself in negative or even narcissistic terms, perhaps even evincing a Freudian sense of self-rejection. This may explain why he was looking for a cause célèbre all his life so that he could dedicate his existence to that cause.

Greece gradually emerges in his poetry. And it is the first time that we do not see a poet during that period who sees the Greeks from their Orientalist point of view or as bad imitations of classical Greeks. Instead, Lord Byron sees the Greeks as they were, using expressions such as Grecian (Grekos) and Romaic (Romios) and avoiding the official description of “Hellene”.

Byron had a very healthy attitude to modern Greeks whereas, according to Dr Karalis, the Classical Greeks had deprived them of the agency of being contemporary because of the prevailing ‘wisdom’ that represented the ancient Greeks as philosophers, poets and so on.

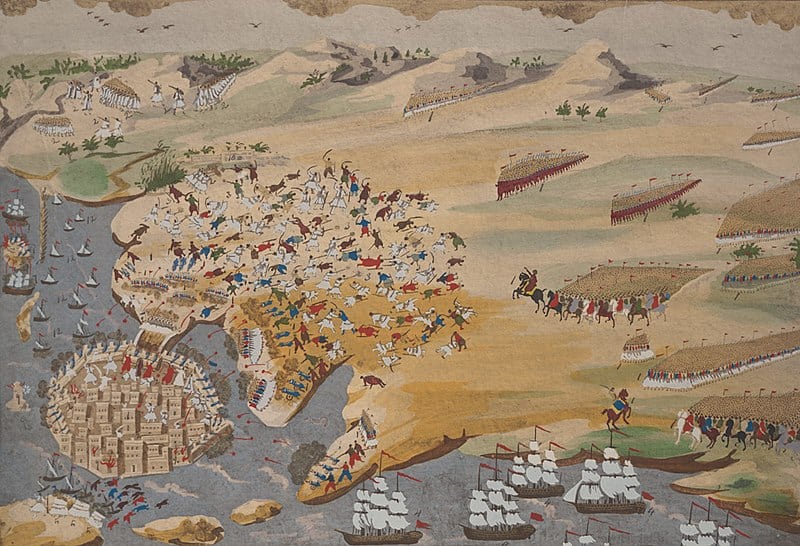

When Lord Byron arrived in Missolonghi in late 1823, the town was blockaded on all sides by the Egyptians, the Ottomans and Albanian forces, as depicted in the famous painting by Dimitrios Zografos. Byron had a pessimistic view, fearing that it would all collapse and famously wrote at the time in his journal: “I came here to join a nation, not a faction”.

However, it turned out that Missolonghi was a famous turning point.

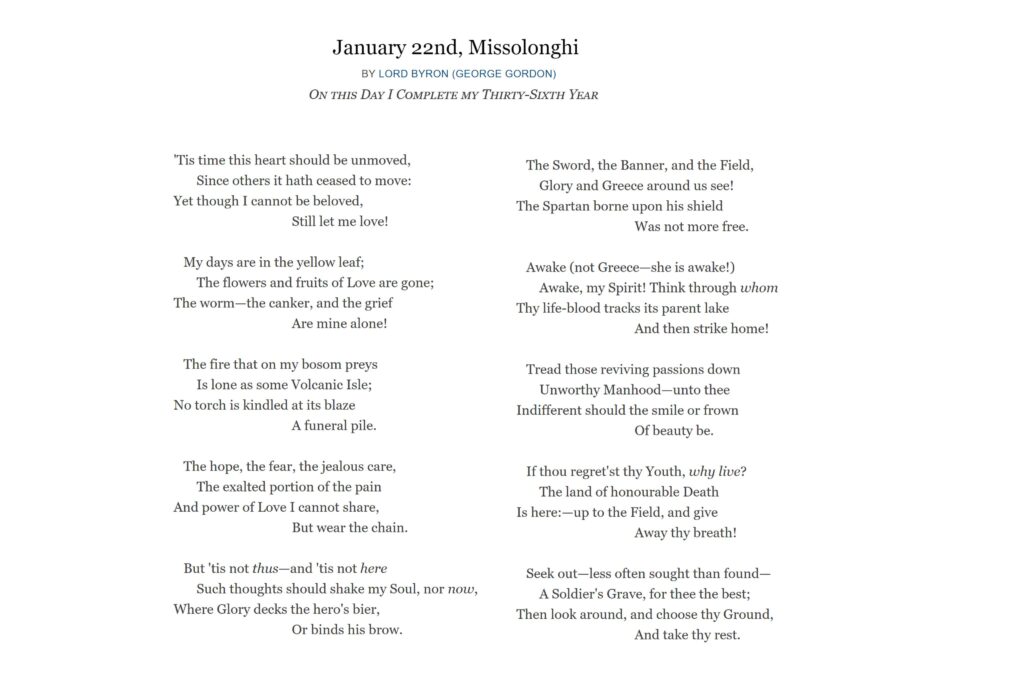

On the day of his last birthday, 22 January 1824, Byron had been inspired by his recent arrival in Missolonghi to write a poem reflecting the inspiration and motivation which he found in the Greek struggle for independence and an acceptance of self-sacrifice over self-indulgence for a noble cause.

The final solemn stanza is prophetic:

The final solemn stanza is prophetic:

Seek out – less sought than found –

A soldier’s grave, for thee the best;

Then look around, and choose thy ground,

And take thy rest.

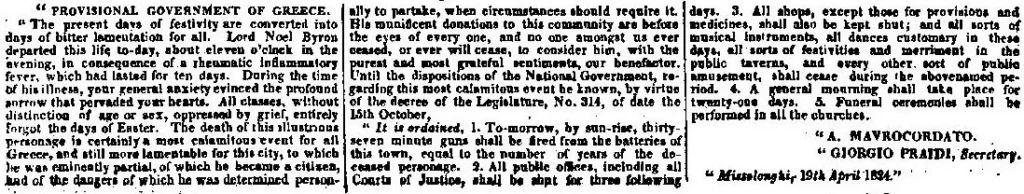

On the death of Byron there was even an official announcement of the death of the poet:

“Thus has perished, in the flower of his age, in the noblest of causes, one of the greatest poets England ever produced.”

And on hearing of Byron’s death, Dionysios Solomos, who would go on to become Greece's national poet was moved to write "On the Death of Lord Byron - Lyrical Poem" (1824), a companion poem to his “Hymn to Liberty”:

Liberty, stop for a moment

Striking with your sword,

And come and weep

Over the body of Byron.

Lord Byron has been described as the “noblest spirit in Europe” who in his own words was drawn to noble, perhaps impossible causes, “when a man hath no freedom to fight for at home”. His musings on Greece’s lost liberty and his calls of “Awake, my spirit” helped to create an even stronger European sympathy for the Greek cause after his untimely death.

The memory of Lord Byron, our Greek Poet, is eternal.

George Vardas is the Greek City Times Arts and Culture Editor