The milk bar is a significant yet underrecognized element of Australian sociocultural history. Emerging in the early 20th century, this institution reflects a confluence of global influences and local ingenuity, largely overlooked due to a historical focus on British-centric narratives within Australian scholarship. This article, informed by extensive research, traces the milk bar’s origins, development, and global dissemination, spotlighting its role as a transformative force in popular culture and a notable Australian export.

Historical Context and Origins

The milk bar’s modern incarnation emerged during the Great Depression of the 1930s, a period marked by economic instability and widespread business failures. Its progenitor was Joachim Tavlaridis, known as Mick Adams, a Greek migrant born on the northern shores of the Dardanelles under Ottoman governance. After migrating to Australia following regional upheavals in the early 20th century, Adams sought to establish a livelihood amid challenging circumstances.

His innovation stemmed from observations made during international travels. In Greece, Adams encountered traditional dairy shops, which piqued his interest in milk-based offerings. Subsequently, he studied the operational model of drugstore soda parlors in the United States—accessible venues where soda fountains served a diverse clientele with refreshing beverages. A key technological observation was the malted milk mixer, a device capable of rapidly producing milkshakes. These experiences coalesced into a vision that Adams brought back to Australia.

The Establishment of the Modern Milk Bar

On November 4, 1932, Adams opened the Black and White 4d—milk Bar in Sydney’s Martin Place, introducing a novel business model. Unlike traditional cafes with table service, this establishment featured a streamlined, counter-based operation focused on rapid customer turnover. The menu emphasized milkshakes—marketed as a health food devoid of the saturated fats and sugars later associated with them—alongside sodas and fruit juices. This approach aligned with contemporary public health campaigns promoting milk as a wholesome tonic, enhancing its appeal.

The venture proved immediately successful. On its opening day, approximately 5,000 customers visited the modest premises. Within a year, weekly patronage averaged 27,000, and by 1937, the number of registered milk bars across Australia reached 5,000. This rapid proliferation underscores the milk bar’s status as a pioneering concept within Australia and globally, distinguishing it from earlier soda parlors and confectioneries.

Cultural Synthesis and Adaptation

The milk bar’s development reflects a synthesis of cultural influences, primarily mediated through Greek migration. Before World War II, Greek immigrants to Australia, including Adams, drew upon their homeland’s dairy traditions and the American soda fountain model, which Greek-American entrepreneurs had shaped. This hybridity manifested in the milk bar’s design—featuring American-inspired elements such as Hamilton Beach milkshake mixers and sleek counters—while adapting to Australian preferences for inclusivity and simplicity.

The institution’s appeal transcended class boundaries, offering an affordable, egalitarian space that contrasted with the exclusivity of British-style eateries. This adaptability facilitated its integration into Australian society, where it became a fixture of everyday life and a symbol of modernity.

Global Dissemination and Influence

The milk bar’s influence extended far beyond Australia’s borders. In 1935, New Zealand entrepreneurs, inspired by Adams’ model, established the Black and White Milk Bar in Wellington, initiating a wave of similar “dairies” across the country. In Britain, Australian businessman Hugh D. McIntosh exported the concept to London’s Fleet Street in the mid-1930s, sparking a proliferation of over 1,000 milk bars within a year. The model further spread to continental Europe—appearing in Poland, Germany, and France—and later reached Pacific nations such as Fiji.

In the United States, however, the milk bar struggled to take root due to the entrenched dominance of soda parlors. It was not until after World War II, when Australian war brides introduced milk bar-inspired milkshakes to American servicemen, that the beverage gained significant traction, particularly in southern states. This belated adoption highlights an intriguing reversal: an Australian innovation reshaping its American precursor.

Evolution and Architectural Expression

Over time, milk bars evolved to reflect changing societal needs. Initially marketed as health-focused outlets offering milkshakes with fresh fruit, nuts, and yeast, they later embraced cultural shifts. By the 1950s, many incorporated jukeboxes and catered to youth subcultures, such as Australia’s “bodgies” and “widgies,” playing swing, jazz, and eventually rock ‘n’ roll. Some establishments diversified into convenience stores, selling newspapers and cigarettes, while others aligned with cinemas, enhancing the association between food and entertainment.

Architecturally, milk bars adopted modernist styles imported from the United States, notably Art Deco and Streamline Moderne. Features such as curved counters, neon signage, and promotional mechanical cows—borrowed from American precedents—underscored their forward-looking ethos. Regional variations emerged: in Western Australia, milk bars often doubled as fruit shops, while in the Northern Territory, powdered milk substituted for fresh dairy due to logistical constraints.

Decline and Contemporary Legacy

The late 20th century brought challenges to the milk bar’s viability. Competition from fast food chains and convenience stores, coupled with a generational shift as immigrants’ children pursued professional careers, led to a decline in their numbers. Many surviving milk bars, such as the Rio Milk Bar in Summer Hill, NSW, or Jerry’s Milk Bar in Melbourne, have adapted into hybrid cafe-restaurants or rely on community nostalgia for survival.

Efforts to preserve this legacy have met with mixed success. In Sydney, a seven-year campaign culminated in installing a plaque in Martin Place, acknowledging Adams’ establishment of the world’s first modern milk bar in 1932. This recognition affirms the institution’s historical significance, though many original sites have been lost to urban redevelopment.

Conclusion: A Lasting Contribution

The milk bar, pioneered by Mick Adams, represents a remarkable intersection of migration, innovation, and cultural exchange. Far from a mere footnote, it reshaped Australian social habits, influenced global food culture, and introduced an enduring beverage—the milkshake—to the world stage. Its legacy persists in the memories of those who frequented its counters and in the few remaining establishments, serving as a testament to the transformative potential of entrepreneurial vision within a multicultural society.

Historic Greek-Australian Archive Finds Permanent Home at State Library of NSW

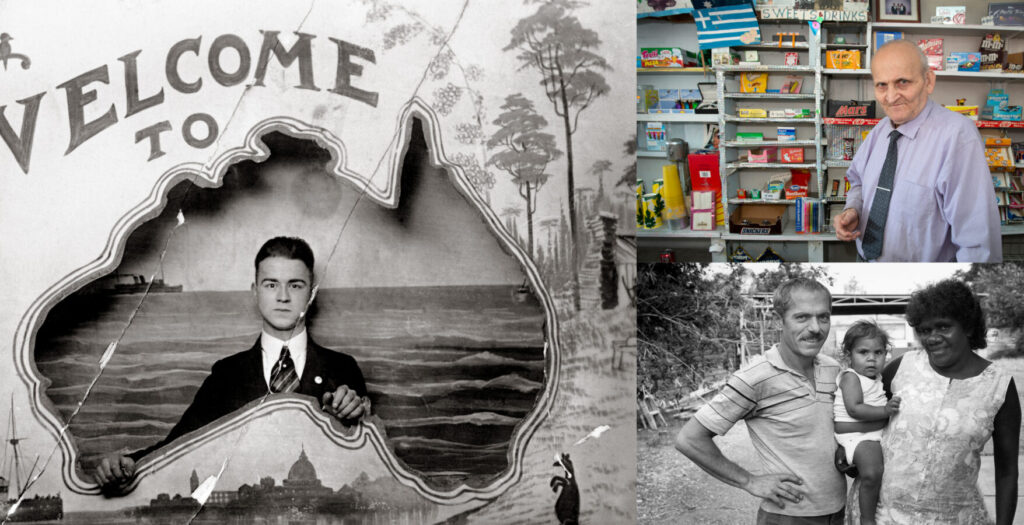

For over four decades, Leonard Janiszewski, a researcher and historian, and Effy Alexakis, a photographer, have dedicated their lives to documenting the rich and often overlooked history of Greek-Australians. Their groundbreaking project, In Their Own Image: Greek-Australians, has become one of the most comprehensive collections of Greek migration, settlement, and identity in Australia.

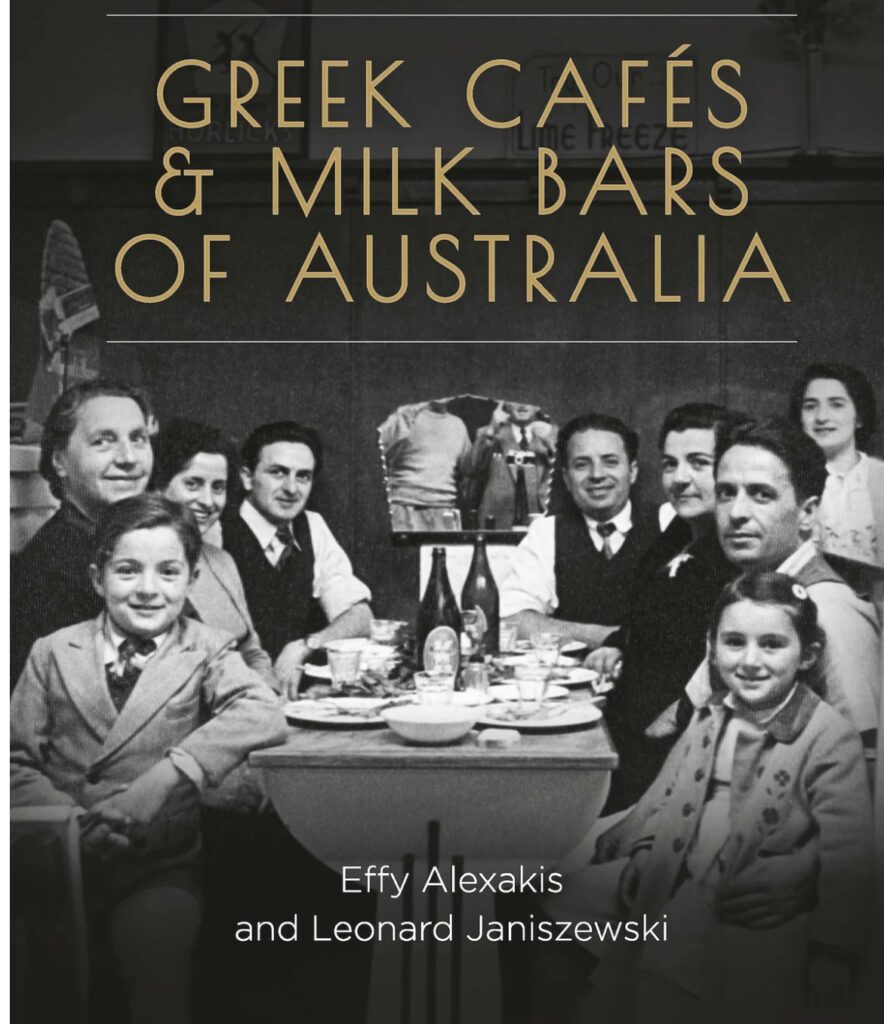

The duo has traveled extensively across Australia and Greece, capturing stories, photographs, and documents highlighting Greek-Australians’ social, cultural, and historical contributions. From Greek cafes and milk bars to the pearling industry and early gold miners, their work spans generations and diverse occupations, vividly portraying the Greek-Australian experience.

In the late 1990s, their efforts gained significant recognition when they partnered with the State Library of NSW and received a Visions Australia Grant. This funding enabled them to create a professional exhibition that toured Greece twice and was showcased in major institutions across Australia. The exposure amplified their work and allowed them to gather even more stories and information.

After years of dedication, Leonard and Effy have decided to gift their extensive archive to the State Library of NSW. The collection, which includes film, cassette tapes, and paper-based documents, is one of the largest and most detailed. Richard Neville, Mitchell Librarian, Learning, Scholarship and Outreach Division at the State Library, expressed his enthusiasm for the archive, stating he was “desperate” for it to be housed at the institution.

However, preserving and digitizing the archive comes with a significant cost. The estimated goal for digitization and database creation is $300,000. Thanks to three recent donations, the fundraising effort is off to a promising start. Leonard and Effy have committed to spending the next 18 months scanning and organizing the materials, ensuring a smooth transfer to the library.

The couple is calling on individuals and organizations to support their fundraising efforts. They are willing to give lectures and assist in any way necessary to preserve the archive. “We feel very grateful and very hopeful,” they shared. “This archive is for future generations to research, learn from, and cherish.”

Their daughter, Connie, family, and friends have witnessed the immense responsibility and dedication required to maintain the archive. Now, with the support of the State Library and the community, Leonard and Effy’s life’s work will be preserved for posterity.

Call to Action:

Donations can be made directly to the State Library of NSW if you would like to contribute to the preservation of the In Their Own Image: Greek-Australians archive. For more information on how to support this historic project, contact the State Library or visit their website: https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/donate-foundation