The new school year has started in Turkey, and it brings terrible news for the country's dying Greek community, as only 281 students will study in seven Greek Orthodox schools in Turkey.

By Uzay Bulut

Journalist Melike Çapan reported in the news website Independent Turkish that twenty-three students graduated from Greek schools this past year, but only thirteen new students enrolled in those schools for the new academic year. Only five or ten new students enroll each year in the schools, five of which are in Constantinople (Istanbul) and two on the small island of Imbros.

The schools receive no funding from the Ministry of National Education; the Greek community foundations in Turkey support them. And only Greek Orthodox students are allowed to study in the Greek schools- a requirement introduced in 1968 by the Turkish Ministry of National Education.

Çapan interviewed the principals of the two Greek schools in Constantinople and the one in Imbros about how these historic educational institutions are struggling to survive. Below is some of the information she presented:

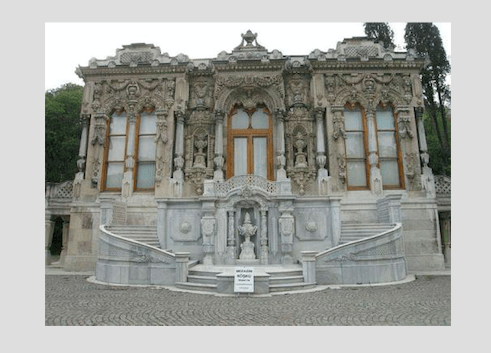

Phanar Greek Orthodox Lyceum: Known in Greek as the Great School of the Nation, the Phanar Greek school was established in Constantinople in 1454. Famous for its magnificent architecture, the educational institution had only forty-three students last year. Five students graduated from its high school while only one graduated from middle school. Six new students enrolled this year. Most are Orthodox students from Hatay, southern Turkey.

Zografeion Lyceum: Established in 1848 in Constantinople, the school had 522 students in its founding year. It currently has fifty students. Eleven graduated this year, while seven new students enrolled.

Imbros (Gökçeada) Private Primary School: Opened as “the Hagia Todori” in 1951 on the island of Imbros in the Aegean Sea, the elementary school was closed by the Turkish government in 1964. It was reopened in 2012 with only four students. The school currently has seventeen students.

These numbers are indicative of the almost complete annihilation of the indigenous Greek people of Turkey by the Turkish government.

The persecution of Greeks, however, did not start with the coming to power of the Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2002. Before, during and after World War I, for instance, the Greeks and other Christians in the Ottoman Empire were exposed to a state-led genocidal campaign that lasted for at least ten years and nearly eliminated them. And sadly, the anti-Greek campaign did not end even after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. In fact, it has systematically continued for decades since the founding of the Turkish republic in 1923. For instance, during its October 1991 fact-finding mission to Turkey, Helsinki Watch found that"

“The problems experienced by the Greek minority today include harassment by police; restrictions on freedom of expression; discrimination in education involving teachers, books and curriculum; restrictions on religious freedom; limitations on the right to control their charitable institutions; and the denial of ethnic identity. These problems are also suffered by the few remaining Greeks living on the islands of Imbros and Tenedos.

“Education is a matter of great concern to the Greek minority. Greek children are not allowed to study Greek history; teachers from Greece who are supposed to teach the children Greek, English, music, gym and art are not permitted to arrive in Turkey until the school year is well under way; Greek-language textbooks are old and out of date; students are discouraged from speaking Greek; and the Greek community cannot control the hiring or assignment of teachers or access to schoolbooks.

“Greeks in Istanbul who met with Helsinki Watch looked over their shoulders apprehensively, afraid their conversations were being observed. A principal of a Greek school continually asked a teacher to lower her voice as she described problems of the Greek children.”

All of that happened in contravention of the 1923 Lausanne Treaty, which recognised the boundaries of the newly established state of Turkey and settled many other issues including the rights of religious minorities in the country. For instance, the Lausanne Treaty gives Greeks in Turkey the right to "establish, manage and control at their own expense, any schools and other establishments for instruction and education, with the right to use their own language... freely therein." Yet, the Greek community has not been allowed to manage and control its own schools.

The 1992 Helsinki Watch report noted that the Turkish government:

- “placed all minority schools under the department of private schools of the Ministry of Education in 1961, thus making them no longer "communal schools" entitled to protection under the Lausanne Treaty,

- prohibited Orthodox clerics from entering the premises of Greek minority schoolsin 1964,

- banned from Greek schools morning prayer, Greek textbooks and encyclopediasin 1964,

- in the same year, began refusing permission for the repair of dilapidated school buildings and withdrew recognition of elected schoolboards of the Greek community.

- A retired primary school teacher reported that, although there is no law saying children cannot speak Greek in school, the Turkish directors of the schools tell the students that they must speak Turkish, even in the halls.

- The Greek community has also been angered by Turkish attempts to take over schools that can no longer be used for their original purpose, due to the shrinking of the Greek population. Once a building is no longer used for its original purpose, Greeks say that the Turks declare it to be abandoned and expropriate it.”

Helsinki Watch concluded that “the Greek minority has been denied equal treatment in education and the right to control its schools, in violation ofinternational human rights agreements, the Lausanne Treaty and the Turkish Constitution.”

At the time of the publishing of the report in 1992, there were only ten functioning Greek schools and around 2,500 Greeks left in Constantinople, the ancient Greek city built by the Emperor Constantine in 324 AD.

Today, Greeks in Constantinople are estimated to constitute fewer than 2,000 in a city of about 15 million.

This decline of population is a result of systematic persecution of Greeks: In 1941, for instance, Greek, Armenian and Jewish males in Turkey were forced into labor camps, under a policy referred to as the "conscription of the twenty classes"– and were forced to work under terrible conditions to construct roads and airports. In 1942, the Turkish government enacted the Wealth Tax Law, as a way of removing Greeks, Armenians, and Jews from Turkey's economy. Those who could not pay the tax were sent to labor camps or deported, or their properties were seized by the government. On September 6-7, 1955, the Greeks of Constantinople became the target of a government-led pogrom, in which Armenians and Jews were also victimised. In 1964, the remaining Greeks in the city, including the disabled, the elderly and the infirm, became victims of a mass expulsion at the hands of the Turkish government. All of these abuses and assaults created such an atmosphere of fear that tens of thousands of Greeks had to leave Turkey.

This systematic campaign against Greeks has resulted in the destruction of numerous Greek Orthodox communities that lived in Anatolia for nearly 3,000 years and left a unique imprint on the land, the landscape and the culture of the region and of the Ottoman and Turkish society as a whole.

The resurgence of Islamism in Turkey and across the Middle East – accompanied by institutionalised human rights abuses and the absolute collapse of the rule of law - could be largely attributed to the forced Turkification and Islamisation campaign that Turkish governments have pursued for decades, which has deprived Turkish society of cultural and religious pluralism and the positive cultural contributions the native Christian peoples made to the region.

About the author: Uzay Bulut is a Turkish journalist and political analyst formerly based in Ankara. Her writings have appeared in various outlets such as the Gatestone Institute, Washington Times, Christian Post and Jerusalem Post. Bulut’s journalistic work focuses mainly on human rights, Turkish politics, and history, religious minorities in the Middle East and anti-Semitism.

About the author: Uzay Bulut is a Turkish journalist and political analyst formerly based in Ankara. Her writings have appeared in various outlets such as the Gatestone Institute, Washington Times, Christian Post and Jerusalem Post. Bulut’s journalistic work focuses mainly on human rights, Turkish politics, and history, religious minorities in the Middle East and anti-Semitism.