Alexander the Great came as an invader to India and the legacy he left behind includes many legends and mythologies, including one the says a planned invasion of India was only stopped in 326 BC by a prophesy the Macedonian king received from the Indian sadhu Kalanus (Calanus).

The following excerpt is from the book “The Murder of Alexander the Great,” by Ajith Kumar.

Anyone familiar with the history of Alexander the Great will easily recognize the name of Kalanus (Calanus, Kalana, Kalanos), the mysterious ascetic Brahman from Taxila who accompanied Alexander throughout his campaign in India.

Arrian wrote: “I have mentioned Kalanus because no history of Alexander would be complete without the story of Kalanus.” The Greeks fittingly called him a gymnosophist, meaning a “naked philosopher.” Kalanus gained a great reputation as an oracle and a philosopher (sophist) in Alexander’s camp.

Kalanus was one of a group of monks belonging to a cult that practiced extreme asceticism. They sowed no seeds nor reaped any grains; they neither built homes nor wore any clothes.

They displayed their complete contempt for the propriety and comforts of civilized life by discarding both clothing and shelter.

These mendicants, as is usual with the eastern mystic cults, lived in the open in Taxila, usually exposed to the harsh elements of nature. Because life’s miseries start with the want for basic human needs, they restricted their physical and mental needs to the barest necessities for survival.

The first appearance of Kalanus in front of Alexander is incredibly theatrical, and it had unpredictable consequences in the life of the great Macedonian general.

Arrian has recorded the intriguing episode thusly: “On the stately appearance of Alexander and his huge army at the city gates of Taxila, some naked Brahman ascetics standing by the roadside dismally stamped their feet on the ground and gave no other signs of interest.”

Philosopher tells Alexander to strip naked

General Onesecritus, who was sent by Alexander to fetch these sadhus, says that Kalanus was lying naked, resting on a stone, when he first saw him, and that he, therefore, approached him and greeted him. Kalanus told him that if he wished to learn, he should take off his clothes, lie down naked on the same stones, and thus hear his teachings.

Later, the Greek historian Plutarch confirmed this record, stating “As to Kalanus, it is certain that King Taxiles prevailed with him to go to Alexander.” Kalanus soon accompanied the army up to Persia, and Alexander took his “impartial” spiritual advice all throughout the campaign.

Later events prove that Kalanus was part of a major military strategy defined by the Indian sages as “kuta-yuddha,” or the Battle of Intrigue. The Indians tactically planted Sadhu Kalanus in the barracks of Alexander, thereby successfully infiltrating the enemy camp.

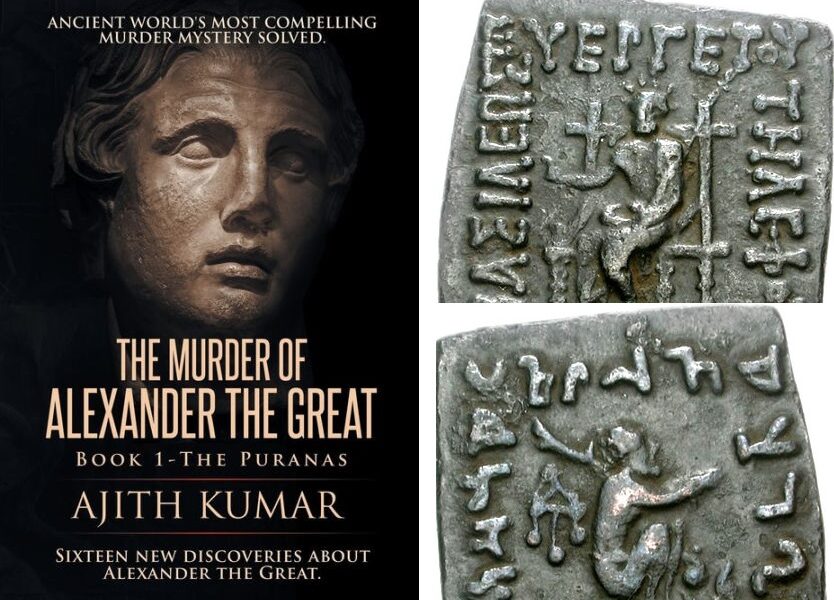

Amazingly, a solid piece of evidence in the form of a coin that portrays the real image of Kalanus has survived all these centuries in the legendary city of Taxila.

The coin, issued by King Telephos of Taxila, depicts the icon of Kalanus with that name. King Telephos appears to have issued the coin as a tribute to Kalanus, who had miraculously stopped Alexander on the altar in Kurukshetra and helped the Indians to recapture the throne of Taxila.

The commemorative coin records the decisive defeat of Alexander and confirms the end of his Indian conquest in Punjab. On the reverse side of the coin, a naked Indian sadhu is featured sitting on an altar of stones and offering a fire sacrifice.

This image has perplexed most scholars because no other coin ever depicts the icon of a sadhu Brahman, on the side on which, notably, the king’s image customarily appears. Shockingly, however, on this coin, King Telephos had boldly replaced the image of Alexander with that of Sadhu Kalanus.

The Kharosthi legend on the coin reads: “Maharajasa Kalana kramasa Telephasa.” The corresponding Greek legend on the other side of the coin reads: “Basileos Eyepgetoy Thlefoy.”

As the Greek word eyepgetoy means “inherited divine power,” we can assume that the corresponding Kharosthi word kramasa on the other side of the coin also means eyepgetoy, or divine inheritance.

Plutarch narrates story

The ancient Greek historian Plutarch narrates what happened on the altar in Punjab, before Alexander decided to stop his Indian invasion:

It was Kalanus, as we are told, who laid before Alexander the famous illustration of state government. It was this. He threw down upon the ground a dry shrivelled hide, and set his foot upon the outer edge of it; the hide was pressed down in one place, but rose up in others.

He stepped all around the hide and showed that this was the result wherever he pressed the edge down, and then at last he stood in the middle of it, and amazingly, it was all held down firm and still.

The metaphor was designed to show that Alexander ought to put most constraint upon the middle of his empire and not wander far away from it.

After a few minutes, as the sacrifice ended on the altar, Alexander declared to the crowds that he accepted the oracular advice of the Brahman, and the war campaign in India ended abruptly. Alexander announced to the crowds that the sacrificial omens were averse to proceeding.

This event alone eventually helped to change the inflexible resolve of Alexander and altered the course of world history. Plutarch offers further insight into this:

When there was a profound silence throughout the camp, and the soldiers were evidently annoyed at his wrath, without being at all changed by it. Ptolemy, son of Lagus, says that he nonetheless offered sacrifices there for passing the river.

But the sacrificial victim was unfavourable to him when he sacrificed. Then he collected the oldest of the Companions and especially those who were friendly to him, and as all things indicated the advisability of returning, he made known to the army he had resolved to march back.

“How far can you go, Alexander, in India? No further”

A legend on the ancient Roman road map called the Peutinger map, written by the side of the altars in Punjab, said in ancient Latin: “Hic Alexander responsum accepit.”

About what followed the altar sacrifice and the demonstration by the oracle (Sanskrit: Sadhu), we have the testimony of Arrian in the Anabasis (Arrian, Anabasis, 5.28.) as follows:

When there was a profound silence throughout the camp, and the soldiers were evidently annoyed at his wrath, without being at all changed by it. Ptolemy, son of Lagus, says that he nonetheless offered sacrifices there for passing the river.

But the sacrificial victim was unfavourable to him when he sacrificed. Then he collected the oldest of the Companions and especially those who were friendly to him, and as all things indicated the advisability of returning, he made known to the army he had resolved to march back.

The legend on the ancient Roman road map, the Peutinger map, engraved by the side of the icon of the altars, said in ancient Latin: “Hic Alexander responsum accepit. Usque quo Alexander.”

The Roman emperor Augustus had ordered the creation of this map in 12 BC. The map was engraved in marble and put on display in the Porticus Vipsania in the Campus Agrippae area in Rome.

The curious label on the map means, “Here Alexander accepted the oracular advice to the question: How far can you go, Alexander?”

“No further,” the Indian priest himself had answered.

This sentence is the most significant evidence, literally carved on stone, that proves that Alexander stopped his military campaign in India on the advice of the sadhu (oracle) Kalanus.

READ MORE: Inscription dedicated to Ancient Greek god of the wild found in Byzantine-era church in the Golan Heights.