On 14 October 2023 Australians will be voting in a referendum to amend the Australian Constitution to recognise Australia’s First Peoples through the framework of an advisory body known as the Voice to Parliament.

Whilst this referendum has aroused considerable passion and controversy on both sides of the political divide, sadly it has also seen deliberate misinformation, fearmongering and extremist propaganda, not to mention latent racism, rise to the surface once again.

As a proud Greek-Australian writer whose parents came to Australia during the mass migration waves immediately before and after World War II, and who respects the rich and varied threads of the multicultural society that is Australia, I believe that the moral and legal case for voting Yes is compelling.

There have been a number of forums held across the country within the Greek-Australian community as community groups, the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese and a number of associations have come out in support of the Voice.

A migrant community respecting the indigenous generations that have always been here.

An inconvenient history

Terra Australis Incognita was ‘discovered’ by Captain James Cook in 1770 but quickly became terra nullius, land that was legally deemed to be unoccupied or uninhabited. Australia’s First Peoples were banished by the stroke of a colonial pen and, to make sure, at the same time massacred in the frontier wars unleased by the colonists.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century a push began for the creation of a federation of states. A series of constitutional conventions were held, leading to the drafting of the Australian Constitution by representatives of the colonies, including both conservatives and liberals, protectionists and free traders, in what Professor Nicholas Aroney, a constitutional law academic, and darling of the naysayers in the current referendum debate, has described as a “formative process” which together with the constitutional principles and values that were pre-supposed, informed the deliberations and shaped the institutions created by the Constitution.

The First Nations Peoples – or what was left of them (as they were regarded as a ‘dying race’) – were neither consulted nor taken into account. In other words, no indigenous voice was heard, let alone taken into account.

And the constitution made no mention of Australia’s indigenous history and heritage but included several provisions that allowed discrimination on the basis of race, notably the so-called race power whereby the Australian Parliament can use to make laws – both positive and adverse – about their rights. The First Peoples were also initially excluded from being counted in the official census for voting purposes.

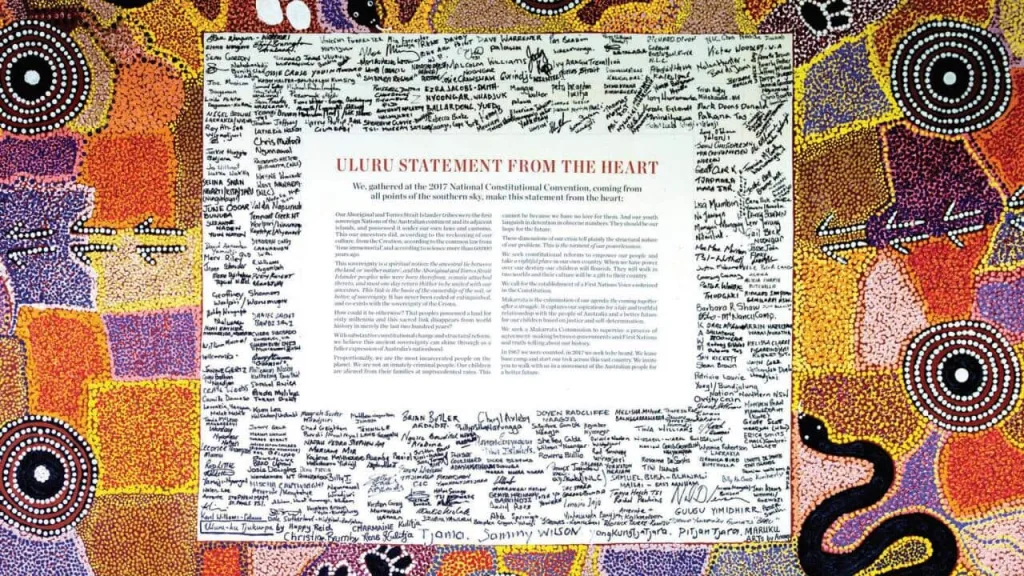

The Uluru Statement from the Heart

The concept of the Voice primarily emerged through the work of the Referendum Council appointed by the Federal Parliament in December 2015. The Council conducted a series of First Nations Regional Dialogues, culminating in the National Constitutional Convention at Uluru in May 2017 at which the Uluru Statement from the Heart was unveiled – desperate plea literally from the heart and soul of First Peoples – calling for “constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country”, including the establishment of a “First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution”.

The Referendum Council – supported by a Constitutional Expert Group of leading constitutional lawyers – subsequently recommended that a referendum be held to provide in the Constitution for a representative Voice to the Commonwealth Parliament to overcome what was described as the “torment of our powerlessness”, highlighted by their dispossession, the effects of the frontier wars and the forced removal of children into protective missions, deaths in custody, higher incarceration rates and adult and infant mortality rates

Although the 1967 referendum gave Parliament the power to legislate with respect to Indigenous rights, it did not empower Indigenous peoples to have a say in the exercise of that power. According to the Uluru Statement, “in 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard”.

The Referendum Question: Yes or No

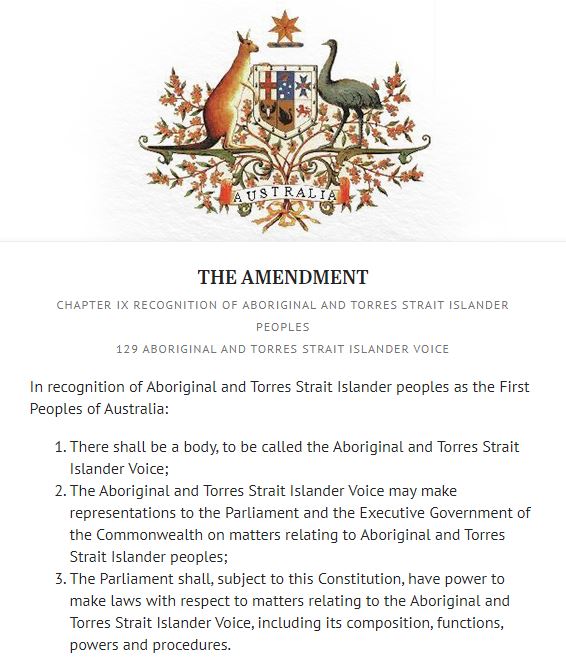

The proposed change to the constitution and the question which voters are asked to decide is the addition of s.129 in the following terms:

The Solicitor-General and second law officer of the Commonwealth of Australia, Stephen Donaghue KC, in a legal opinion given on 19 April 2023 concluded that the proposed amendment is not only compatible with the system of representative and responsible government established under the Constitution, but actually will enhance that system to the extent that it will facilitate more effective input by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in public discussion and debate about governmental and political matters relating to them.

As the High Court has held, the principle of representative government “signifies government by the people through their representatives” which is the essence of the exercise of legislative power.

The Solicitor-General concluded that the new Section 129 would not alter the existing distribution of Commonwealth governmental power since it does not confer legislative, executive or judicial power upon the Voice. Simply stated, the Voice would have no power to make laws, to develop or administer policies or to decide disputes. Nor would it form part of either the Parliament or the Executive Government but instead would operate only as an advisory body with no power of veto.

A democratically-elected parliament is empowered to legislate to specify the extent to which consideration of representations made by the Voice is required:

“Even if decision-makers do have to consider some representations of the Voice in certain contexts, all that would mean is that the decision-makers must (within the bounds of rationality and reasonableness) … have regard to what is said in the representations, bring their mind to bear upon the facts stated in them and the arguments or opinions put forward, and appreciate who is making them. From that point, the decision‑maker might sift them, attributing whatever weight or persuasive quality is thought appropriate. The weight to be afforded to the representations is a matter for the decision-maker.”

From Oxi (No) to Nai (Yes)

At a meeting on the Voice held by the Greek Orthodox Community of Sydney in early October, the film producer and director, Kay Pavlou, gave an emotionally-charged speech, starting with reflections on her own background as an Australian of Greek Cypriot origin whose parents arrived in this country in 1950. Ms Pavlou lamented that the Greek Cypriots forcibly expelled from the northern (and now occupied) part of Cyprus after the Turkish military invasion in 1974, had lost half of their country, their culture, their language and access to their churches. Australia’s indigenous peoples have lost more, including sacred places.

First nations people have special rights; they know this land, but they still do not have a loud voice.

Kay Pavlou added:

“We have an ancient history as Greeks but the aborigines have an even older culture and we value that culture … as Greeks we know we can change history with one word – OXI (meaning no) when the Greeks said no to the fascists in World War II. On 14 October 2023 it is our chance to say yes and change history.”

How would the Voice work?

There has been much written about how the Voice would work, with alarmist claims that it will be divisive, inequitable, racially discriminatory and would effectively assume the mantle of government because it will distinguish the First Peoples from any other group and would mean the end of parliamentary democracy as we know it.

This is palpable nonsense.

Interestingly, the former Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating has recently come out in support of the Voice and has provided a concrete example of how the proposed advisory group would operate.

In 1992 the High Court in the famous Mabo case held that the common law could recognise the native title of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people under their traditional law and custom. The Court rejected the argument that the acquisition of sovereignty by the British Crown itself (in the sense of legal authority to deal with the land) had extinguished pre-existing native title.

In response to this landmark decision the Keating Labor Government legislated the Native Title Act with the assistance of a standing indigenous advisory group during the government’s dealings with business and farming groups and state governments.

According to Keating, this indigenous ‘voice’ to the executive government and the parliament, which was able to provide the quality and poignancy of advice and experience that Indigenous people across the country possessed, informed the government in its deliberations in what was a deeply complex issue and showed how a voice can dramatically benefit policymaking and improve outcomes. In the former Prime Minister’s view:

“The long and tortuous seven months extended consultation through the native title process was the first and, so far, the only example of a ‘voice’ in the full throat of its advisory mandate but as it turned out, a mandate that went a long way to settling perhaps the primary Indigenous grievance: the theft of their estate.”

Mr Keating also told The Australian:

“The consultation was the very first episode of an Indigenous ‘voice’ speaking directly to the executive government on a matter materially central to Indigenous people; namely, that the High Court had found Indigenous people possessed a private property right to their own soil – but a right immediately threatened with extinguishment by malevolent state governments … The challenge was to meet and settle two fundamental objectives: justice for Aboriginal people along with the development of a workable, fair system of land management in Australia.”

This was an excellent example of what the Voice can offer: the opportunity for First Peoples to give informed, coherent and reliable advice to the Parliament and the Executive to achieve a mutually desirable outcome.

Challenging the myths and misinformation of the No campaign

The eminent jurist and former Chief Justice of the High Court, Robert French, has perfectly summed up the adverse reaction to the referendum for the Voice, pointing out that there are three salient factors that the No campaign either ignore or deliberately misinform:

(a)The Voice is not about race but about the historical status of our First Peoples as the indigenous people of Australia. The constitution is race-based and the referendum merely seeks to redress this historical anomaly.

(b)By providing for The Voice in the Constitution, the Australian people are asked to finally recognise and acknowledge the First Peoples as the bearers of the first history of our continent which stretches across tens of millennia.

(c)The constitutional provision creates a democratic mandate for the Parliament to create and continue The Voice as a significant institution in our representative democracy.

The issue of race is also contentious. As the Crikey political commentator, Bernard Keane, has succinctly put it, this is a simple restatement of the terra nullius lie that no-one was here when the British arrived:

“Those who maintain that there should be a constitutional recognition but reject the idea of a Voice to Parliament or indeed any mechanism for consultation with indigenous people as to the form of that recognition, are in effect seeking recognition “on white terms” in a de facto perpetuation of 240 years of white supremacy.”

In reality, as far as Robert French is concerned, the Voice is a “once in a lifetime opportunity” for Australia to fill a gaping hole in our Constitution – our nation’s ‘birth certificate’ – to recognise our first history and the First Peoples who bear it and the painful legacy of its collision with the second history of colonisation. In that way, it will empower First Peoples and the Australian people as a whole to acknowledge, address and move forward from the legacy of their colliding histories.

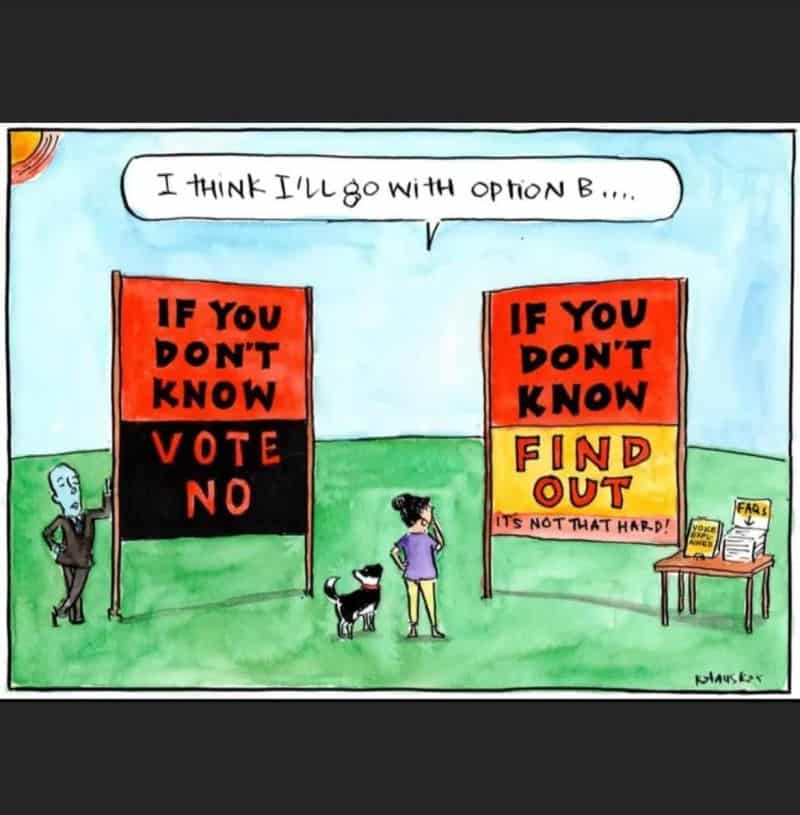

Ignorance is bliss

One of the truly appalling features of the No campaign is the brazen appeal to voter ignorance and apathy which is encapsulated in its crass and cringeworthy cry “If you don’t know, vote no”.

This bogan slogan has drawn criticism from many quarters.

The former High Court Chief Justice Robert French has remarked that the Australian spirit which this battle cry purports to evoke is “a poor shadow of that which started us out on our constitutional journey … (for) … it invites us to a resentful, uninquiring passivity”.

Or, as the Herald journalist Peter Hartcher has written, it is tantamount to an appeal to a frightened country, uneasy about our legitimacy, unreconciled to our First Peoples, and potentially frightened of the future whilst choosing to ignore or forget our bloodied past.

Australia, I would like to think that you are better than that.

Fear and loathing in the No campaign

The conservative hysteria that has been generated apparently knows no bounds.

Fringe dwellers, ranging from neo-Nazis to fellow far right extremists and racist bigots, have reared their ugly heads and made the campaign all about white supremacy and the perceived threat to White Australia if, God forbid, Aborigines could get into the ear of government. We must defend our precious non-indigenous bodily fluids by defeating this insidious referendum question.

As the former Liberal Party leader John Hewson has noted, the enduring strain of the White Australia policy – “the most significant blemish on this country’s national character and unity as well as its global reputation” – is not far from the surface in this referendum campaign as latent racism persists.

It has indeed been a “dominant undercurrent in the public discourse”, stirred most recently by the disingenuous and racially-charged comments of former Prime Minister John Howard urging voters to “maintain the rage”.

Rage against what? Recognition of our First Peoples? Acknowledgement of the historical wrongs visited upon their ancestors?

Howard, who has expressly disavowed Australia’s notorious colonial past by declaring that he does not subscribe to the “black armband” view of Australian history, is but a Tory manifestation of what Professor Larissa Behrendt, a prominent Australian legal academic, writer and indigenous rights advocate, has described as “white blindfold”.

And not to be outdone, the leading naysayer and failed Liberal Party candidate, Warren Mundine, has outrageously labelled the Uluru Statement from the Heart as a “symbolic declaration of war” against modern Australia, taking a leaf out of the Donald Trump playbook

As Bernard Keane observes, Trump’s Make America Great Again mantra drew its strength from white grievance and the positioning of the privileged majority groups as the real victims of far less powerful, disposed minorities.

The No campaign has at times reached hysterical lows, even within the local Greek-Australian community, where social media is littered with what can best be described as incoherent diatribes, born out of white privilege and ignorance.

Some of the ‘pearls of wisdom’ include:

It will be a Voice comprised of a few elitist and wealthy Aboriginal people who have had control of and failed thousands and thousands of vulnerable Aboriginal people for decades.

Aboriginal people on the Voice panel will never agree on anything.

The fact that the Voice will be advisory only and its representation not binding on government means that it will be powerless and the whole exercise is a waste of time. On the other hand, as an advisory body it will have power and “force the Government to do as the Voice instructs them”.

Many of the architects of the Voice are communists.

A Treaty will follow after the Voice which could mean that “non-Aboriginal people will eventually not be able to continue to live in Australia or (will) have to pay more annual reparations to stay here”.

A Yes vote is not a vote for Aboriginal people. It is a vote to give more power to corrupt and wealthy Aboriginal people. And if people do not support or feel welcome in the “British influenced aspect of Australia” (whatever that means) they should go back to their original countries as Australia was British controlled when most non-British people migrated here.

If you don’t know, go low.

The cruel irony is that, if the no scare campaign prevails, then as the activist Noel Pearson has written, we will be in this peculiar situation “where people who have been here for 235 years will have rejected the request for recognition by people who have been here for 60,000 years”.

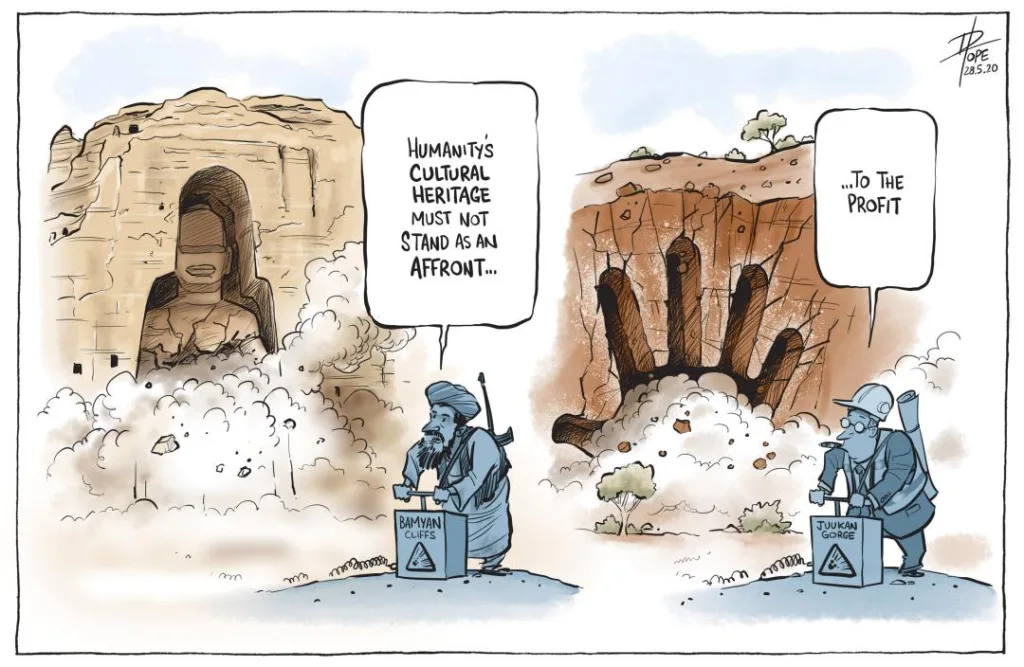

Destruction of Indigenous Cultural Heritage

On 24 May 2020, a sacred rock shelter at Juukan Gorge in the Pilbara region of Western Australia was blasted by the multinational mining corporation Rio Tinto. According to an archaeology report, this rock formation was regarded as of the highest archaeological significance in Australia containing a cultural sequence spanning over 40,000 years, with a high frequency of flaked stone artefacts, rare abundance of faunal remains, unique stone tools, preserved human hair and with sediment containing a pollen record charting thousands of years of environmental changes.

In response to this disgraceful episode of destruction of Aboriginal sacred sites the Western Australian Government in 2021 introduced a new Aboriginal Heritage Act which came into force on 1 July 2023. Precisely 39 days later, it was repealed after extreme pressure was applied by farming, pastoral and mining interests who claimed the new law was too onerous and burdensome.

Was there an indigenous voice heard in this process, do I hear you ask? I daresay, no.

The very people most affected by this blatant and disgraceful exercise in indigenous cultural heritage destruction were overlooked.

Enough said.

Recognition from the heart

Professor Larissa Behrendt wrote a poignant essay in 2017 in The Honest History Book which included this prescient observation:

“The imagery of Australian law is a striking one. The white scaffolding cannot be touched and Indigenous recognition is only permissible to the extent that the framework is left in place.”

The framework of the Australian Constitution should not be frozen in time. The Voice Referendum is simply ensuring an indigenous voice in the Constitution that gives advice to government in matters affecting our First Nation peoples and their descendants.

As Niki Savva, the well-known Australian political journalist, adviser and writer (and herself of Greek-Cypriot background), has bluntly put it:

“This is a defining moment for Australia. Almost every other country on earth has reached accommodation with its original inhabitants. We should at least be honest enough to admit that if we don’t, this debate will have simply exposed what lurks just beneath the surface.”

Yes indeed.

George Vardas is the Arts and Culture Editor of Greek City Times. He is also the Secretary of the Australian Hellenic Council (NSW) and has recently been appointed to the Multicultural NSW Advisory Board. The views expressed in this opinion piece are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of those entities or organisations.